Lobster Fishing Areas 27 - 38

Integrated Fisheries Management Plan

The 2022 Lobster IFMP has replaced this content.

(Homarus americanus))

Foreword

The purpose of this Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) is to identify the main objectives and requirements for the inshore lobster fishery in Maritimes Region, namely Lobster Fishing Areas 27-38, as well as the tactics that will be used to achieve these objectives. This document also serves to communicate the basic information on the fishery and its management to employees of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), legislated co-management boards and other stakeholders. This IFMP provides a common understanding of the basic rules for the sustainable management of the fisheries resource.

Through IFMPs, DFO Maritimes Region intends to implement an ecosystem approach to management across all marine fisheries. The approach considers impacts extending beyond those affecting the target species and, in this respect, is consistent with the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Implementation will take place in a step by step, evolutionary way, building on existing management processes. Advances will be made incrementally, beginning with the highest priorities and issues that offer the greatest scope for progress.

This IFMP is not a legally binding instrument that can form the basis of a legal challenge. The IFMP can be modified at any time and does not fetter the Minister's discretionary powers set out in the Fisheries Act . The Minister can, for reasons of conservation or for any other valid reasons, modify any provision of the IFMP in accordance with the powers granted pursuant to the Fisheries Act .

Where DFO is responsible for implementing obligations under land claims agreements, the IFMP will be implemented in a manner consistent with these obligations. In the event that an IFMP is inconsistent with obligations under land claims agreements, the provisions of the land claims agreements will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.

Signed: Regional Director, Fisheries Management, Maritimes Region

Table of contents

1. Overview of the fishery

1.1 History

Inshore lobster is 1 of the oldest managed fisheries in Canada. The harvesting of inshore lobster can be traced back to pre-colonial times when it was an important food source for Aboriginal peoples who harvested lobster (jakej) through the spring and fall using traps and spears.

By the mid-eighteenth century, various trapping methods had been developed to catch lobsters, culminating in the evolution to the parlour trap in the early 1900s that still forms the basis for the types of traps in use today.

In 1884, the first lobster cannery was established. This helped shift the sale of locally harvested lobster away from a strictly domestic market to a more international market, predominantly Great Britain. The sale of live lobsters has expanded significantly and this product form has been the mainstay of the industry since the Second World War.

Since the late 1800s, numerous regulations have been applied to the lobster fishery. Most regulations initially were based on market requirements and considerations and not on biological concerns. In 1873, the first regulatory measures were introduced to establish restrictions on soft shell lobsters and egg bearing females. Fishing seasons were introduced in the Bay of Fundy area as early as 1879, with additional size restrictions coming into play in 1899. However, throughout the late 1800s and up until the mid-1900s enforcement of these initial regulations was very sporadic and inconsistent. Figure 1 outlines the historical trend in landings and shows where some of the regulations were introduced.

Following almost a century of varied and inconsistent management and regulatory approaches, the present day fishery is the result of a number of initiatives first introduced in the late 1960s. In 1967, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) introduced a limited entry licensing policy for portions of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick and expanded this application of the policy to the remainder of the Maritimes in 1968. Prior to that, no restrictions were in place for acquisition of a lobster licence. Along with limiting the number of licences, the department introduced trap limits and defined boundaries for most of the modern day lobster fishing areas (LFAs).

In 1976, the so called moonlighter policy was introduced with the aim of removing from the fishery those not dependent on it for their primary source of income. Three categories of licences were created:

- Category A licences for those fully dependent on the fishery;

- Category B for those not fully dependent but with a historical attachment to the lobster fishery since 1968; and

- Category C licences that had little or no dependency and which expired in 2 years.

Category B licences were eligible to fish 1/3 of the trap limit for a Category A licence. Under The Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada , 1996, Category B licences have never been transferable and expire upon the death of the licence holder.

Figure 1: Historical landings and introductions of regulations

Description

Figure 1: This charts shows the historical landings from the lobster fisheries and introductions of regulations.

In 1978 to 1981, a lobster licence buy-back program was implemented to reduce the number of participants and in particular those who were not dependent on the fishery. Approximately 1500 licences were retired in Nova Scotia (1406) and southwest New Brunswick (170).

In the mid to late 1980s, regulations were strengthened to include requirements for escape vents and biodegradable panels to be installed in lobster traps to limit ghost fishing (capture due to lost, dumped or abandoned fishing gear). In 1995, following a decline in landings from the 1991 peak, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada requested that the Fisheries Resource Conservation Council (FRCC) review the state of the lobster fishery in Atlantic Canada. Their report, A Conservation Framework for Atlantic Lobster (FRCC95.R.1), concluded that the elements key to achieving a healthy fishery are good egg production, a reasonable mortality and a biomass composed of several year classes. In 1997, after 2 years of consultation, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans identified as a target the doubling of eggs per recruit as a means of conserving and sustaining lobster stocks. A 4-year period, from 1998 to 2001, was the timeframe fishermen had to put in place measures that would achieve the doubling target at some future point.

At the direction of the Assistant Deputy Ministers of Science and Fisheries Management, a small DFO working group was formed to examine the results of the 4-year plans to double eggs per recruit (1998-2001). The Report of the Lobster Conservation Working Group (2001) indicated that the management changes in Maritimes Region LFAs were relatively minor and that by-and-large they failed to meet the specific target of doubling eggs per recruit. There were 2 notable exceptions to this, LFA 27, which had implemented significant minimum size increases, and LFA 30, which was already at or above the target level set by the FRCC of 5% egg production expected in an un-fished population. Changes that did occur included minor increases in minimum legal carapace size, a maximum size on females in LFA 30, a window size restriction in LFA 31A and adoption of a voluntary v-notching program by harvesters in all LFAs except LFA 31A and LFA 27.

In July 2007, the FRCC published their second report, Sustainability Framework for Atlantic Lobster , in which they identified low eggs per recruit, poor stock structure, high exploitation rates and poor compliance as the 4 key risks to the long-term sustainability of the Atlantic inshore lobster fishery. In response to the FRCC recommendations, Maritimes Region identified 3 priorities:

- improve the accuracy of information and data collected and specifically improve the reporting of landings (logs);

- implement measures in each LFA to provide more protection for mature female lobsters (broodstock) and begin to identify issues associated with expanding effort and exploitation levels; and

- improve the overall governance and stewardship of the resource through the consultation process.

As a result of these recommendations the requirement to submit lobster monitoring documents was added to the licence conditions. Progress has been slow in addressing the latter 2 concerns.

In 1990, the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision in R. v. Sparrow. In this landmark decision, the Court provided meaning and context to the Constitution Act, 1982, section 35(1) and held that, after conservation and other “valid legislative objectives”, Aboriginal rights to fish for food, social and ceremonial (FSC) purposes have priority over all other uses of the fishery. Through the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy, DFO provides a framework for the management of fishing by Aboriginal peoples for FSC purposes. Agreements are negotiated and the Minister or delegate issues a communal licence to reflect the agreement reached, or when an agreement is not reached, the Minister issues a communal fishing licence consistent with the provisions of Sparrow and subsequent Supreme Court of Canada decisions.

1.2 Type of fishery

Currently, the inshore lobster fishery consists mainly of a large commercial fishery, which occurs throughout Maritimes Region, and an FSC fishery. There are also opportunities for educational licences. There is currently no authorized recreational harvesting of lobster. Any development of a recreational fishery would require additional policy research and would occur under provisions of the Atlantic Marine Recreational Fisheries Policy.

1.2.1 Commercial

The commercial fishery is licensed under the Fishery (General) Regulations of the Fisheries Act and, in the case of Aboriginal groups, the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations . Regulations specific to commercial lobster fishing are contained in the Atlantic Fishery Regulations and LFA-specific licence conditions.

1.2.2 Food, social and ceremonial

The FSC fishery is licensed under the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations . The fishery is a cultural and sustenance activity undertaken by First Nations and other Aboriginal groups. DFO develops agreements for Aboriginal fishing for FSC purposes. Through these agreements, licences are issued outlining the locations, methods, gear types, timeframes and other conditions for the FSC fishery. The resources fished using an FSC licence are used communally to provide food and support the traditional social and ceremonial activities of the First Nations community or Aboriginal groups.

1.2.3 Educational

Charter boat excursions promoting the lobster fishing experience have been popular with tourists. In the early 2000s, Maritimes Region approved a number of requests for an educational licence to support this. As interest increased, a regional policy was developed (Educational Licence Policy – Lobster / Rock Crab) to ensure consistency in the issuance of these licences and proper management of the activity.

The policy allows for educational licences to be issued with an allocation of up to 3 modified (non-fishable) lobster or rock crab traps that can be set within an area and for a period of time specified in the licence. A handful of grandfathered individuals remain eligible for educational licences that authorize the use of regular (fishable) traps. Regardless of which type of trap is authorized, the licence holder is required to release back to the water any lobsters or other species that may be captured.

Those issued an educational licence are expected to have at least 1 individual on board the vessel with a general knowledge of the fishery and they are expected to promote resource conservation with clients. In this way, the policy promotes tourism and public education and it supports the diversification of economic opportunities within coastal communities. Licences are available to core fish harvesters, charter boat operators and Aboriginal groups. Applications and renewals can be made online through the DFO Maritimes Region website .

1.3 Participants

1.3.1 Commercial

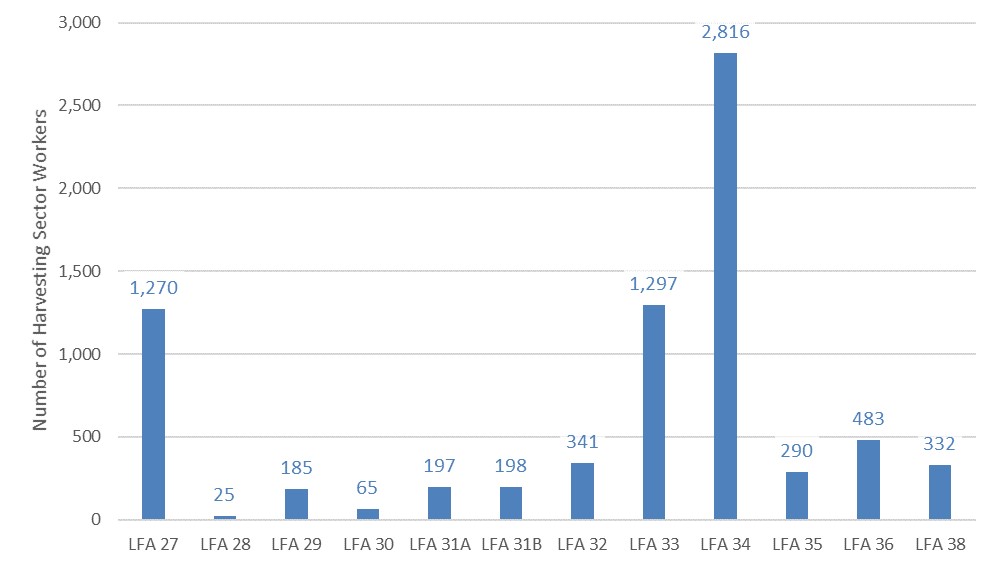

Almost all Maritime Region coastal communities are now involved in the inshore lobster fishery. With few exceptions, all of the approximately 3,000 licences are active during the lobster season, employing approximately 7,500 fishermen. Starting in 1999, in response to the Marshall Response Initiative, Aboriginal access to the commercial fishery has been increased.

Participants are issued a licence that provides access to a specified LFA. The inshore fishing areas consist of LFAs 27 through 38. Current numbers and types of licences by LFA are presented in Table 1. No licences are issued solely for LFA 37. LFA 37 is a small area that is shared by those with a licence for either LFA 36 or LFA 38. When fishing in LFA 37, LFA 36 and 38 licence holders are subject to the conditions of their primary fishing area.

A summer fishery is authorized within the western portion of LFA 38 outside of the regular LFA 38 season. The portion of LFA 38 fished during the summer is referred to as Area 38B (the Disputed Zone). The area is claimed as territorial waters by both Canada and the United States. All fish harvesters holding an LFA 38 licence are eligible to apply for an Area 38B licence. Applications must be made annually. The number of vessels active in the Area 38B fishery has increased in recent years from under 10 to close to 60.

| LFA | Category A | Category B | Communal commercial | Total |

| 27 | 491* | 12 | 12 | 515 |

| 28 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 14 |

| 29 | 53 | 5 | 5 | 63 |

| 30 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 31A | 68 | 3 | 0 | 71 |

| 31B | 70 | 0 | 0 | 70 |

| 32 | 147 | 4 | 6 | 157 |

| 33 | 634 | 28 | 21 | 683 |

| 34 | 944 | 0 | 35 | 979 |

| 35 | 75 | 2 | 17 | 94 |

| 36 | 161 | 1 | 15 | 177 |

| 38 | 119 | 1 | 16 | 136 |

| All | 2,789 | 56 | 134 | 2,979 |

*Includes 35 licences based in Gulf Region. Source: Maritimes Region Licensing Summary Report (LS4041A) and Gulf Region Licensing Office.

In April 2007, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans announced the Policy for Preserving the Independence of the Inshore Fleet in Canada’s Atlantic Fisheries (PIIFCAF) intended to promote a commercial fishery in Atlantic Canada with a strong independent inshore sector. PIIFCAF created the independent core category as new eligibility criteria for the receipt of new or replacement inshore fishing licences. All heads of core enterprises, including those who have inshore lobster licences issued in their name, are now required to declare their status as independent core, meaning not party to controlling agreements with respect to the inshore fishing licences issued in their name.

Under PIIFCAF, if the department has reason to believe that a licence holder has been categorized as independent core but does not meet the criteria for the independent core category, the licence holder’s categorization is reviewed. If a licence holder is found to not meet the criteria for the independent core category, they will not be eligible to be issued the licence that is subject to the controlling agreement in the following or subsequent years.

Since 1968, licensing policy has allowed 2 lobster harvesters (Category A) to form a partnership. Under a regular partnership, 2 licence holders fish using 1 vessel that is licensed for 150% of the trap limit for a single licence. Both operators must be on board. In 2008, an economically difficult period, a new option became available to licence holders where 2 independent core licence holders were permitted to form a flexible partnership. In a flexible partnership, only 1 of the licence holders was required to be on board the vessel. In 2017, following departmental consideration of flexible partnerships, it was concluded it was important, in support of the independence in owner-operator fisheries, to remove this policy option. Regular partnerships continue to be an option for lobster licence holders.

Independent core licence holders have also been able to acquire, by transfer, a second licence that is stacked with the existing licence in the enterprise. The new licence can be fished with 150% of the trap limit of a single licence. The licence holder must be the operator. The 2 stacked licences can later be unstacked and reissued to other eligible persons, subject to all applicable licensing policy provisions.

In the fall of 2016, policy restrictions were introduced in response to concerns that some of the flexibilities made available to the lobster fishery were being used to circumvent the requirements set out in PIIFCAF by unintentionally supporting licence leasing. There were also concerns that those who formed partnerships mid-season could too easily acquire additional tags and that this was leading to an increase in licence holders fishing above the trap limits.

As a result, 2 restrictions were introduced to:

- eliminate the option of in-season partnering: while partnerships can be dissolved during the season, they now have to be formed before the season opens; and

- limit in-season substitute operator authorizations to instances where the substitute operator is fishing on behalf of the licence holder using the licence holder’s gear and vessel.

The PIIFCAF policy does not apply to communal commercial licences.

1.3.2 Food, social and ceremonial

The Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy of 1992 provides access and allocation of lobster resources to Aboriginal people for their FSC purposes.

1.4 Location of the fishery

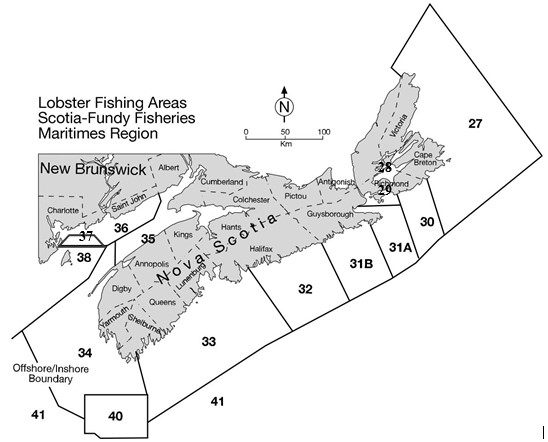

The Maritime Region of DFO extends north from the maritime boundary separating Canada from the United States (the Hague Line). The region consists of the entire Bay of Fundy and all Nova Scotian waters along the Atlantic coast to the tip of Cape Breton. A map of LFAs in Maritimes Region is presented in Figure 2. The coordinates for each LFA are specified in Schedule XIII of the Atlantic Fishery Regulations , 1985.

All fishing occurs inside of 50 nautical miles from shore (90 km) and in eastern Nova Scotia most activity is within 15 km of shore. The 50 nautical mile line divides the inshore lobster fishery (LFAs 27-38) from the offshore lobster fishery (LFA 41). The offshore fishery is managed under a separate IFMP.

Figure 2: Lobster Fishing Areas in Maritimes Region

1.5 Fishery characteristics

The fishery is prosecuted almost entirely by vessels less than 13.7m (45’) length overall (LOA). In LFAs 33 and 34 there is a maximum vessel length of 13.7m. Stern extensions may be added to LFA 33 and 34 vessels, but where the vessels are at maximum length, the extensions cannot exceed 1.52 m (5’). In all other Maritimes Region LFAs, vessels up to 19.8m (65’) LOA may be used.

| LFA | Season | Trap limit¹ | Minimum Legal size (mm) | Other measures |

| 27 | May 15 - July 15 | 275 | 82.5 | |

| 28 | April 30 - June 30 | 250 | 84 | Max. entrance hoop 153mm |

| 29 | April 30 - June 30 | 250 | 84 | Max. entrance hoop 153mm |

| 30 | May 19 - July 20 | 250 | 82.5 | Max. CL-135mm (female) |

| 31A | April 29 - June 30 | 250 | 82.5 | Closed window (female), 114-124 mm |

| 31B | April 19 - June 20 | 250 | 82.5 | V-notching²

|

| 32 | April 19 - June 20 | 250 | 82.5 | V-notching²

|

| 33 | Last Mon. Nov - May 31 | 250 | 82.5 | |

| 34 | Last Mon. Nov - May 31 | 375/400 | 82.5 | |

| 35 |

Oct 14 - Dec 31 and |

300 | 82.5 | |

| 36 |

2nd Tues Nov - Jan 14 and |

300 | 82.5 | |

| 37 |

2nd Tues Nov - Jan 14 and |

|||

| 38 | 2nd Tues Nov – Jun 29 | 375 | 82.5 | |

| 38B | June 30 – Fri before 2nd Tues Nov | 375 | 82.5 |

¹The trap limit is for a Category A licence (full-time). A Category B licence (part-time) is allowed 30% of the limit of a Category A licence and a licence fished under a partnership or stacking arrangement, 150%.

²V-notching means there is an active program to v-notch female lobsters. There is a possession restriction of v‑notched lobsters in all other LFAs except in LFA 27 and LFA 31A.

Season lengths generally range from 8 weeks to approximately 6 months. Seasons, trap limits and other management measures are presented in Table 2.

1.6 Governance

The IFMP for inshore lobster is governed by a number of pieces of legislation and policies including, but not limited to, those noted below.

- Fisheries Act, 1985

- Atlantic Fishery Regulations (AFR), 1985

- Coastal Fisheries Protection Act, 1985

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans Act, 1985

- Atlantic Fisheries Restructuring Act, 1985

- Fishery (General) Regulations, 1993

- Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations, 1993

- Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada, 1996

- Oceans Act, 1996

- Species at Risk Act, 2002

- Sustainable Fisheries Framework: Conservation and Sustainable Use Elements

General regulatory requirements for licensing and registration are found in the Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985 (AFR), Part II. Regulations specific to the lobster fishery are further outlined in Part VI of these regulations. The Fishery (General) Regulations provide the basis for lobster licence conditions and the authority to issue variation orders to change minimum legal carapace sizes and season dates from time to time. Changes to season dates are usually due to inclement weather or ice conditions that could potentially affect the safe opening of an LFA. The Fishery (General) Regulations provide the basis for control over incidental catches.

Since the mid-1980s, advisory committees have acted as the primary vehicles through which industry provides advice to government on management measures affecting the fishery. In most LFAs, a representative and an alternate are elected or appointed by licence holders in their port cluster or geographic area. LFA-specific advisory committee meetings are normally co-chaired by DFO representatives within Maritimes Region area offices and a representative from the industry.

In 2007, the Maritimes Region Lobster Advisory Committee was reinstated. This larger body has representation from each LFA and deals with issues that affect all LFAs or groups of LFAs (Bay of Fundy for example). The committee meets as required or at least once annually and produces formal minutes.

Currently there is no single representative body for the lobster industry in Atlantic Canada.

1.7 Approval process

Licence conditions are reviewed and updated annually. Changes are consulted on and explained to the industry at advisory committee meetings, which are held in every LFA in advance of the opening of the season.

Many decisions affecting the day to day operation of the fishery, such opening dates and times, storage of gear, tag replacement policies and enforcement priorities, are approved by DFO area offices. Resource Management within Maritimes Region Regional Headquarters leads on operational matters affecting LFA 35, as LFA 35 overlaps with multiple DFO areas. See Table 3 for more information.

| LFA | Operational lead |

| 27-32 | Eastern Nova Scotia Area Office, Sydney |

| 33-34 | Southwest Nova Scotia Area Office, Yarmouth |

| 35 | Regional Headquarters, Dartmouth |

| 36-38 | Southwest New Brunswick Area Office, St. George |

Operational leads are responsible for scheduling and chairing advisory committee meetings.

Operational and policy decisions affecting multiple LFAs are generally made within DFO Regional Headquarters. DFO senior management and the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans can be involved in decisions with broad implications.

2. Stock assessment and status

2.1 Biological synopsis

2.1.1 Distribution

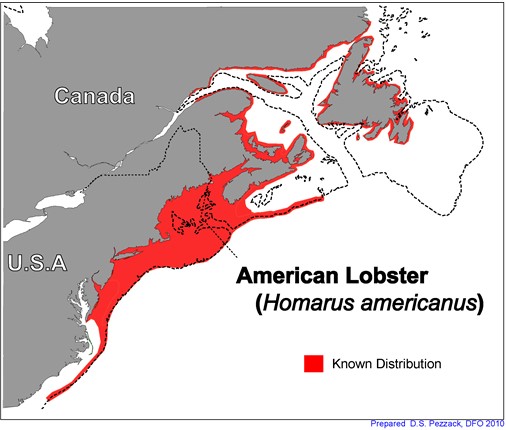

The North American lobster (Homarus americanus) is widely distributed in coastal waters from southern Labrador to Maryland, with the major fisheries concentrated in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Gulf of Maine (Figure 3). Lobsters are also found in deeper waters (down to 750 m) in the Gulf of Maine and along the outer edge of the continental shelf from Sable Island to off North Carolina. This deep water distribution is due to the presence of the warm slope water that keeps the slope and deep basins in the Gulf of Maine warm year-round. This warm deep water is not found on the eastern Scotian Shelf, in the Gulf of St Lawrence or off Newfoundland.

Lobsters are a temperate species that require sufficiently warm summer temperatures to grow, produce and hatch their eggs. Juvenile and adult lobsters can exist in waters from less than 0°C to approximately 25°C. Larval lobsters occur in surface waters between 6°C and 25°C, though a minimum temperature of approximately 10-12°C appears to be required for successful development to the settlement phase (stage IV). Larval development is temperature dependent and takes just 10 days at 22-24°C but over 2 months at 10°C.

At the northern limit of their range (northern Newfoundland) summer temperatures remain too cold for ovary and egg development, while at the southern limit of their range (Maryland coastal and off Cape Hatteras along the slope edge) winter temperatures remain too warm and the moulting and reproductive cycles are not synchronized.

Figure 3: Eastern North American lobster distribution.

Lobsters are found on many different bottom types from mud and sand to cobble and boulders. Young lobsters often seek shelter to avoid predators so are more restricted in their habitat than larger lobsters. Newly settled and juvenile lobsters are most common in complex habitats, such as cobble or gravel bottoms or eel grass. They are also capable of burrowing so can also be found in areas with compact clays or peat reefs. As they grow and become less susceptible to predators they are found in more varied bottoms including open mud and sand bottoms.

2.1.2 Migrations and depth preferences

Adult lobsters make seasonal migrations to shallower waters in summer and deeper waters in winter. Mature lobsters tend to move significantly greater distances than immature animals. Over most of their range, these movements vary from a few km to 20 km. However, in the Gulf of Maine and on the outer continental shelf lobsters undertake long distance migrations of tens to hundreds of km. Tagging studies have shown that at least some of these lobsters return to the same area each year (Campbell 1986; Pezzack and Duggan 1986).

Migrations may be undertaken to optimize the temperature to which lobsters and their eggs are exposed, to avoid shallow water during stormier winter periods and to migrate to areas optimal for hatching eggs and either retention or export of larvae. The triggers for these migrations are not well understood.

Quantitative estimates of exchange rates between areas cannot be given at this time. The mark-recapture approach used in historical studies does not permit discrimination between residences and return migrations after lengthy periods at large, except where intervening recaptures of the same individual lobster are involved. The origin of the animals that are tagged in any 1 location is unknown. Determining the proportion of animals in the population that make long distance movements is confounded by regional differences in the reporting rate of recaptures and the fact that where local fisheries are intense, there is a low probability that legal-sized animals survive to move long distances. The closed season in inshore fisheries also poses a problem in that summer movements would not have been detected in these earlier studies.

2.1.3 Biology

Lobsters in the Maritime Region generally take 8-10 years to reach the legal size of 82.5 mm Carapace Length (CL). At that size they weigh approximately 0.45kg (1 pound) and moult once a year. Larger lobsters moult less often, with a 1.4kg (3 pound) lobster moulting every 2 to 3 years. The largest recorded lobster was 20kg (44lb). The maximum age of lobsters is unknown but based on growth information and long term holding studies it is believed to be in the range of 50 years.

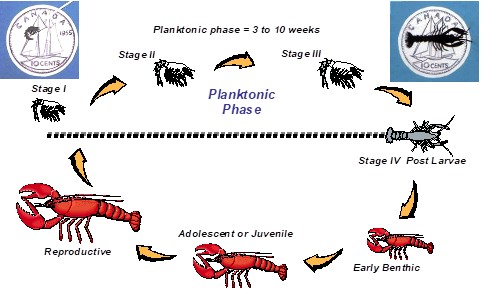

The usual reproductive pattern is for the mature female to mate in late summer while in a soft shell condition immediately after moulting (Figure 4). The male transfers a spermatophore into the seminal receptacle at the base of the female’s tail. Over the next year the eggs develop in the female’s ovaries and during the following summer the eggs are extruded and fertilized, then attach to the underside of the tail. The eggs are then carried for 10-12 months and hatch the following July or August. The larvae spend approximately 4-6 weeks chiefly in the surface waters, although they undergo a daily vertical migration. Halfway through Stage IV they leave the surface waters and actively seek preferential habitat, which is typically characterized by rough gravel or cobble bottoms, though they can also settle in eel grass and in areas with hard clay or mud sediment that is conducive to burrowing. Stage I to IV lobsters feed on a variety of plankton species and predominantly on cladocerans, copepods and crab larvae (Harding 1992).

Figure 4: Lobster life cycle.

The young lobsters are vulnerable to many predators, so for the first few years on the bottom they remain in or near their shelter, then spending more and more time outside the shelter as they grow larger (Lavalli and Lawton 1996).

Little is known about the larval distribution along the inshore regions of south and eastern shores of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton as detailed circulation models are lacking. In these areas lobsters are typically more restricted to the coastal bays and it is thought that while larval exchange occurs along the coast, much of the larvae are likely retained in the local areas.

Models of ocean currents for the Gulf of Maine have been used to infer larval lobster distribution (Drinkwater, Hannah et al. 2001). It has been recognized that these models do not include lobster larval behaviours, which may influence the patterns of connectivity. These models indicate strong retention of larvae on Georges Bank. Browns Bank shows weaker retention, with potential exchange of larvae from Browns to German Bank or to the Bay of Fundy. These models show little potential for exchange from Browns Bank to the nearshore areas of southwestern Nova Scotia or the south shore inside the 50m isobath (Drinkwater, Hannah et al. 2001). The models suggest that near shore settlement is from larvae hatched in nearshore areas. There is little exchange of larvae from Browns Bank to coastal Maine but that there is potential for larvae from Maine to settle in the Browns Bank region (Xue, Incze et al. 2008).

Lobster stock structure is not fully understood, but genetic analyses looking at the entire species range observed a north/south separation with a relatively homogeneous population to the north (centered in the Gulf of St. Lawrence) and more heterogeneous populations in the south (centered in the Gulf of Maine and the Mid-Atlantic Bight region (Kenchington et al. 2009). At smaller geographical scales, studies identified areas of low gene flow between some areas, which are likely to be shaped by ocean currents and lobster migration patterns (Benestan et al. 2015).

2.1.4 Reproductive potential

Female lobsters reach maturity at different sizes and ages over their geographic range and this is thought to be controlled principally by local water temperatures (Aiken and Waddy 1986; Waddy and Aiken 1991; Comeau and Savoie 2002), maturing at smaller sizes in regions with warm summer temperatures (Gulf of St. Lawrence, southern New England) and at larger sizes in regions with cooler summer temperatures (Bay of Fundy).

The maturity measure used by scientists is the size at 50% maturity, which is the size at which half of the animals are capable of reproducing. In females this is determined through dissection or examination of the cement glands on the pleopods (swimmerets), evaluation of ovarian maturity or other metrics. Male maturity is not usually estimated due to the fact it requires dissection and because past work indicates that it occurs at a similar or slightly smaller size than the females under the same conditions. For successful mating the male needs to be similar in size or larger than the females. If males are too much larger, then mating success is reduced. Males can mate with numerous females and it has been shown that there are consequences of having too few males as mating success and clutch size is reduced through sperm limitation (Pugh 2014).

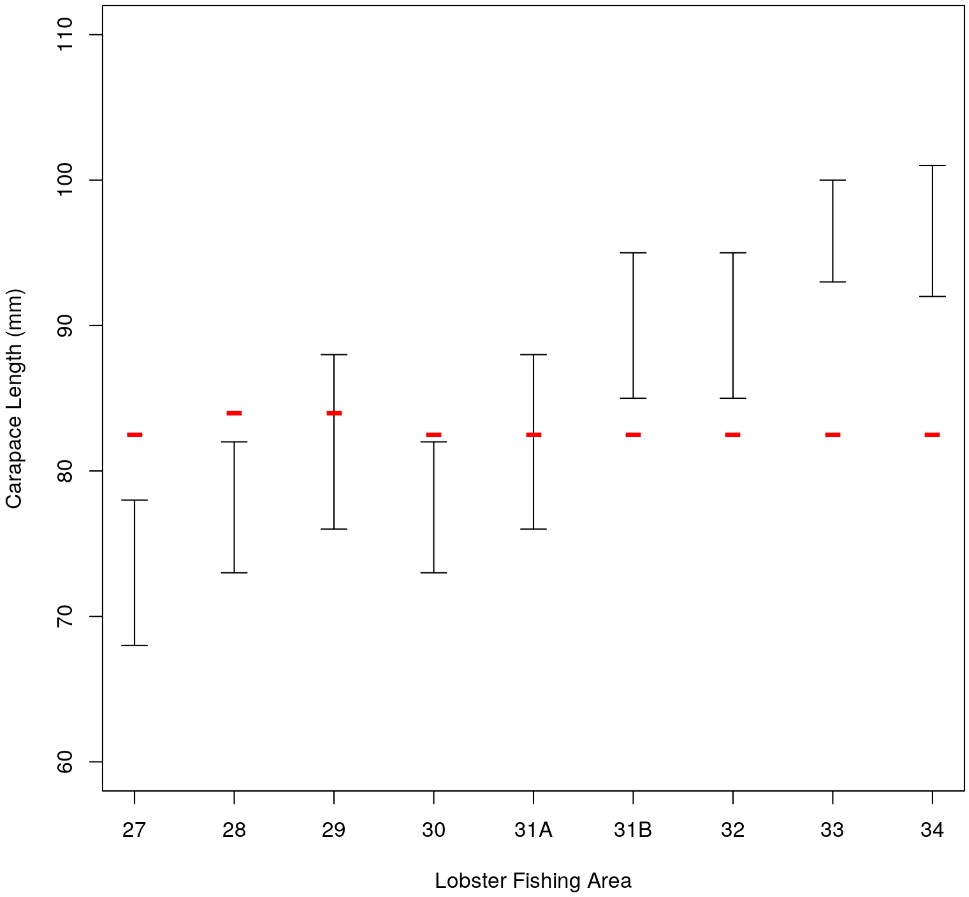

Maturity estimates are presently being re-evaluated but the best estimates available at this time are given in Figure 5 (the vertical bars represent what science considers the likely potential range).

Figure 5: Lobster size at 50% maturity by LFA (where available).

Description

Figure 5: This chart shows the lobster size at 50% maturity by LFA, where available.

At maturity, female lobsters will usually produce eggs every second year. Based on laboratory studies using ambient inshore Bay of Fundy water temperatures, larger female lobsters appear able to spawn twice without an intervening moult (consecutive spawning) at sizes greater than 120mm CL (Waddy and Aiken 1986) though this size may vary under actual conditions (Campbell 1983; Comeau and Savoie 2001; Comeau and Savoie 2002). Consecutive spawning occurs in 2 forms: successive-year (spawning in 2 successive summers, a moult in the first and fourth years) and alternate-year (spawning in alternate summers). In both types, females often are able to fertilize the 2 successive broods with the sperm from a single insemination (multiple fertilizations). Intermoult (hard-shell) mating has also been observed in laboratory conditions (Waddy and Aiken 1990).

Consecutive spawning and multiple fertilizations enable large lobsters to spawn more frequently over the long term than their smaller counterparts. This combined with the logarithmic relationship between body size and numbers of eggs produced, means that large lobsters have a much greater relative fecundity. The advantages of a population that includes a good mix of sizes including very large sizes is well documented (DFO 2009). For lobsters the advantages include higher egg production and different hatching areas and times. This should result in less susceptibility to short term fluctuations in recruitment levels.

2.1.5 Natural mortality

Natural mortality (M) has been estimated for some nearshore lobster populations and is generally assumed to be between 10-15% for all fully recruited legal sized animals (Fogarty and Idoine 1988) and in most models it is assumed to be the same over time and for all size groups. However in reality this could vary greatly depending upon habitat, predator abundance, time of the year and lobster size.

A constant M is usually chosen using a life history criterion, such as longevity, growth rate and age at maturity. American lobsters have a relatively long life span and slow reproduction and are thus classified by biologists as k-selected with low natural mortality after the larval stage. The uncertainty of the natural mortality is in part due to the lack of an accurate ageing method.

2.2 Ecosystem interactions

2.2.1 Predation on lobsters

During the larval stage, lobsters are eaten by many plankton feeding fish and invertebrates. During the settling stages as the lobster moves from the plankton to the bottom to find shelter they are preyed upon by many small fish, such as cunners, sculpins and invertebrates like small crabs. During their first 3 to 4 years, lobsters remain in or near their chosen shelter to avoid predation from visual predators including many fish species, such as sculpin, cunners, skate, crabs and other opportunistic feeders (Lavalli and Lawton 1996). There is evidence that natural mortality varies inversely with body size with larger lobsters safer from all but the largest predators; however all lobsters are most vulnerable immediately following the moult when their shell is still soft. Animals that have been identified as predators on lobsters in some areas include sculpins, skates, cod, spiny dogfish, sea ravens, wolfish, Cancer crabs and striped bass. Mortality levels on the inshore lobster stocks have not been quantified. Anecdotal information indicates that seals are a predator on lobster; however there is no scientific data on the prevalence or level at which it may occur.

2.2.2 Food sources for lobsters

Lobsters are both active and opportunistic feeders. Lobsters are active predators of crabs, clams, mussels, scallop, various gastropods, fish, marine worms, sea urchins, starfish and small amounts of marine plants. They will also feed on an opportunistic basis on dead fish and other organisms (Carter and Steele 1982; Elner and Campbell 1987; Gendron, Fradette et al. 2001).

2.2.3 Species interactions and interactions with other fisheries

Other Crustaceans

Lobsters co-occur with other crustaceans of commercial value, most notably Jonah crab (Cancer borealis), rock crab (Cancer irroratus) and deep-sea red crab (Chaceon quinquedens). While Jonah and rock crab can co-occur in shallower waters and are caught either as a directed fishery or as a bycatch of lobster fisheries, red crab generally exist in greater water depths than commercial lobster distributions and rarely make up a significant portion of bycatch.

Rock and Jonah crab can be retained for bait (in specified LFAs) and must be recorded in the lobster log, though the level of recording appears to be low in some areas.

The commercial rock and Jonah crab fisheries use traps similar to the lobster fishery and have the potential for lobster bycatch. While the bycatch cannot be retained, there is the potential for some damage to lobsters, particularly during the moulting period.

Other fisheries

While other fisheries cannot legally land lobsters, there is potential interaction with bottom mobile gear. Observer data indicates their presence in the catch of scallop, trawl and gill nets set on the bottom. There is little quantitative information available as to the level of capture or survival of lobsters returned to the water by different gear types. Observer data from the inshore scallop fishery in Scallop Fishing Area (SFA) 29 showed that the number of lobsters caught was very small (<0.1%) compared to the number of lobsters caught by the directed trap fishery in LFA 34 (DFO. 2018/044). Of the lobsters caught, the majority were alive and uninjured. Levels of damage or mortality on the bottom are unknown.

Interaction with whales, turtles and seals

Right whales are present on the Scotian Shelf in summer and the mouth of the Bay of Fundy and Roseway Basin has been identified as summer feeding habitat. Other whale species present in coastal waters are humpback, pilot, various dolphin species, minke and fin whales. While there is potential for interaction between lobster gear and whales, the inshore lobster fishing seasons do not often overlap with times of known whale concentrations. However, little is known of whale migration routes between the summer and winter grounds.

Industry in some LFAs has adopted a set of protocols to further reduce the potential for interaction between whales and fishing gear.

There is also potential for interaction with sea turtles, though reported interactions between whales/turtles and lobster gear are rare.

Seals are known to eat lobster bait and can cause damage to traps.

2.2.4 Gear impacts

A DFO national science advisory process to examine the potential impacts of traps and other gears on marine habitats and communities was held in January 2010. A Science Advisory Report from the workshop is available (DFO 2010/003) and titled “Potential impacts of fishing gears (excluding mobile bottom-contacting gears) on marine habitats and communities.”

Report conclusions

The potential impact of traps on marine habitats is dependent on a variety of factors, including:

- Characteristics of the bottom where they are set (sediment type, relief and depth);

- Weight, size and construction material of traps;

- Retrieval methods and sea state, weather, tides, currents;

- Type of rope (floatlines are less likely to entangle bottom structures);

- Soak time;

- Use of anchors or weights; and

- String configuration (e.g. length) can affect degree of entanglement on bottom.

An assessment of the impact on marine habitats of lobster traps in particular has not been conducted, but numerous reviews of trap impacts have concluded that the potential for impact is small, though they agree that it could increase with density and frequency of the traps being hauled (Eno, Macdonald et al. 2001; Morgan and Chuenpagdee 2003; Chiarella, Stevenson et al. 2005).

The study by Eno et al. (1996) suggests that the direct contact of fishing gears with fauna may not be the primary cause of mortality and the frequency and intensity of physical contact is more likely to be important.

The trap footprint on the sea bottom is small and traps are weighted to restrict movement caused by currents. The area affected is thus limited primarily to the trap footprint area (< 0.62 m²) and the area of disturbance as the trap is hauled. Proper hauling results in minimal dragging of the trap along the bottom, though greater movement can occur especially in rough weather.

The type of bottom fished is varied (e.g., cobble, ledge, mud, sand, gravel) and includes some high energy areas with large natural sediment movements. The impact of traps on the bottom will vary depending on the bottom type where they are deployed and the spatial extent of deployment.

2.2.5 Gear loss and ghost fishing

Gear loss has not been quantified regularly but is believed to be low as gear is valuable and efforts are made to recover lost traps through grappling. Lost gear would remain intact for considerable periods of time unless disturbed by weather or mobile gear. However, all traps in every LFA are fitted with biodegradable panels, which will open after a period of time in order to mitigate ghost fishing.

2.2.6 Non retained bycatch

Pressure from the inshore lobster fishery in the Maritimes Region is not known to exert a direct impact upon ecological system structure or functioning (including specific prey or predator species) although no specific studies have been conducted. All non-approved species must be immediately returned to the water. Survival of returned bycatch has not been measured but is believed to be high for most invertebrates; however could be low for fish.

Bycatch species include: rock and Jonah crab; sea urchins; whelks; and various fish species, including cusk, cod and sculpins. A survey of bycatch in LFAs where data is available is reported during stock assessments. A broader catch monitoring initiative began in fall 2018, which will provide more robust bycatch estimates.

2.2.7 Environment interactions

Water temperature is a controlling factor in growth, reproduction, movements and distribution of lobsters. Temperature also affects lobster catchability (the likelihood that they will enter traps) (Drinkwater, et al. 2006). Wind and water currents influence larval distribution and movement and temperature controls larval duration.

The net effects of climate change on lobster populations are difficult to predict. Areas will be influenced both by local changes and changes in large scale ocean conditions, such as the near shore Nova Scotia Current and the Labrador Current along the shelf break. Cooling conditions could reduce larval survival, growth and increase the size at maturity. Warming conditions could increase larval survival, growth and decrease the size at maturity. Warming conditions could also result in changes in predator mix and the potential for increased disease.

2.3 Stock assessment

Lobster assessments are conducted periodically through the Regional Assessment Process (RAP) coordinated by the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS). The target frequency for full assessments for each LFA is every 5 years. The assessments are peer reviewed and information is made public through publications available online in the form of Stock Advisory Reports (SAR), Research Documents and meeting proceedings (Table 4).

Stock structure has not been fully described. The current hypothesis is that the lobster is a stock complex comprised of several sub-populations that are linked through larval drift and adult migration patterns. In 2011, a cluster analysis of historical landings from 1947 onward indicated that there were 5 groupings of LFAs in the inshore with similar patterns in landings: LFA 27, LFAs 28-32, LFA 33, LFA 34 and LFAs 35-38 (Tremblay et all 2011). For a period of time, stock assessments were completed according to these groupings, with sub-analyses completed for individual LFAs. In 2018, a framework assessment was held for LFAs 27-33. A recommendation from this later framework was that the LFAs be examined separately because each is managed separately and because several possess unique conservation measures that may affect trends in stock status indicators. Furthermore, assessing stocks independently was considered to be a more precautionary approach.

| LFA | Stock advisory report (SAR) / Stock status report (SSR) | Research document |

| 27-30 |

1996/116 |

1996/141 |

| 31-32 |

1996/117 |

1991/21 |

| 33 |

1996/117 |

2004/071 |

| 34 |

1996/118 |

1999/032 |

| 35-38 |

1996/119 |

1999/031 |

2.4 Precautionary approach

2.4.1 Policy requirements

In 2009, DFO adopted A Fishery Decision-Making Framework Incorporating the Precautionary Approach (PA Policy) as a component of the Sustainable Fisheries Framework. The PA in fisheries management is, in general, about being cautious when scientific knowledge is uncertain, unreliable or inadequate and not using the absence of adequate scientific information as a reason to postpone or fail to take action to avoid serious harm to the resource. This approach is widely accepted as an essential part of sustainable fisheries management. The primary components of the PA framework are stock status indicators and reference points; a harvest strategy, including removal references (the maximum acceptable removal rates for the stock); harvest control rules; and explicit consideration of uncertainty and risk.

2.4.2 Preliminary approach and data sources

There are currently no working population models for Canadian lobster with which to set model-based reference points. An indicator-based approach to setting reference points across all of the inshore LFAs has therefore been adopted.

In 2012, landings-based reference points were adopted for each of the LFAs (DFO 2012). Due to the input-based management of this fishery and the long-term consistency of management measures, landings were assumed a reasonable proxy for biomass, at least in the short term. At the time, landings were also the only indicator of lobster biomass with a significant time series.

Given the uncertainties and caveats associated with the use of landings, other primary and contextual indicators were added to the stock assessment framework for each LFA, based on available data sources. These other indicators could both change the perception of stock status and inform the type of management response to a stock should it enter the Cautious Zone.

In 2018, a framework assessment was completed for LFAs 27-33. The framework and subsequent stock assessment resulted in a new set of stock status indicators and reference points for these LFAs. The next framework assessment for LFAs 34 and 35-38 is scheduled for 2019 and in the meantime the preliminary indicators and reference points remain in effect.

2.4.3 Indicators and reference points: LFAs 27-33

Primary indicator

The primary stock status indicator for LFAs 27-33 is the commercial catch rate. The time series is made up of 2 data sources: the first is a voluntary log book, which began in the 1980s and continued until 2013 in some LFAs; and the second is the current, commercial log book, which is now mandatory and has been mandatory in some LFAs since the mid-2000s. The 2 data sources are treated as a single, continuous time series.

The combined catch rate data series from 1990 to 2016 was used to define the upper stock reference (USR) and limit reference point (LRP) for each LFA. This time period represents periods of both low and high productivity for lobster and it covers approximately 2 generations. The median of this time series is considered to be a proxy for biomass at maximum sustainable yield (BMSY). Consistent with guidance in the PA Policy, the USR and LRP are set at 80% and 40% of the BMSY proxy.

The metric used to compare the commercial catch rate to the USR and LRP is a 3-year running median. A running median was chosen over an average as the median dampens the impact of anomalous years, which may occur due to factors other than changes in abundance.

| LFA | BMSY proxy: Median of the commercial catch rate 1990-2016 | USR: 80% of the BMSY proxy | LRP: 40% of the BMSY proxy |

| 27 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| 28 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| 29 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| 30 | 0.7 | 0.56 | 0.28 |

| 31A | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.16 |

| 31B | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.16 |

| 32 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.14 |

| 33 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.14 |

Secondary indicators

There are 3 secondary stock status indicators for LFAs 27-33: landings (kg) and effort (numbers of trap hauls) from the commercial log books and catch rates of sub-legal (70 to <82.5 mm) and legal-sized (≥82.5 mm) lobsters from the recruitment trap survey (kg per trap haul).¹ Commercial landings are related to population abundance, as fishery controls are based on inputs (effort) rather than outputs (total allowable catches). Fishing effort can be a proxy for fishing pressure and is an important indicator of fishery performance. The recruitment trap survey provides the best information on abundance of undersized lobsters and it is the only data on abundance that is collected in a standardized manner.

Secondary indicators represent important time series trends that are tracked individually. No reference points are defined for these.

Contextual indicators

Contextual indicators describe biological processes that influence production, changes in the ecosystem and changes in the performance of the fishery. They include indices of berried female lobsters, indices of new recruits, size-based indices, idealized reproductive potential, biomass recruits, proportion of new recruits, proportion of mature lobsters and bottom temperature. Specific reference levels are not applied to contextual indicators.

The contextual indicators are included in full stock assessments. They are presented in a multivariate analysis, with a matrix plot showing trends over time.

Indicator of exploitation

A Continuous Change in Ratio (CCIR) method is used to estimate exploitation. Change in ratio methods provide estimates of population parameters based on the changes in observed proportions of components within the population, in this case lobsters just below the minimum legal size (a reference, non-exploited component) and new recruits to the fishery (an exploited component). The premise of this method is that the proportion of reference individuals within the population will increase with the cumulative removals from the exploitable component.

Data for the CCIR analysis is drawn from the recruitment trap survey from the period of 2000 to 2016 (with some variation among LFAs). Since this is a period of increased productivity, it has been assumed that the estimated maximum exploitation rate from the time period is likely below the rate that would have negative impacts on the lobster stocks or, in other words, below fishing at maximum sustainable yield. The removal reference (RR) for each LFA is defined as the 75th quantile of the posterior distribution of the maximum modeled CCIR exploitation rate.

| LFA | 75th quantile of the posterior distribution of the maximum estimated CCIR exploitation rate, 2000-2016 |

| 27 | 0.84 |

| 28 | Not developed |

| 29 | 0.94 |

| 30 | 0.77 |

| 31A | 0.89 |

| 31B | 0.82 |

| 32 | 0.84 |

| 33 | 0.81 |

2.4.4 Indicators and reference points: LFAs 34 and 35-38

Primary indicators

Landings (t) is the primary stock status indicator in LFA 34 and LFAs 35-38 (LFAs combined). For the landings indicator, the median of landings from the period of 1985 to 2009 was accepted as a proxy for BMSY. This time period represents a productive period for lobster, but it also includes years in which landings were substantially lower than they are currently. The USRs and LRPs are calculated as 80% and 40% of the BMSY proxy respectively. The metric for assessing where the stock is relative to the USR and LRP is the 3-year moving average of landings

| LFA | BMSY proxy: median of landings 1985-2009 | USR: 80% of BMSY proxy | LRP: 40% of BMSY proxy |

| 34 | 11,084 | 8,867 | 4,433 |

| 35-38 | 1,969 | 1,575 | 782 |

In each of the LFAs, other primary indicators are used to interpret changes in the landings indicator. Commercial catch rate (kg landed per trap haul) is a primary indicator based on commercial logbook data. In LFA 34, the USR is defined as 80% of the median catch rate for the reference period of 1998-99 to 2008-09. In LFAs 35-38, the USR is 50% of the median for the reference period 2005-06 and 2008-09. Fifty per cent was selected over 80% because the time series is shorter for these LFAs and it was a very productive period.

In LFA 34 a lobster-focused trawl surveys being developed out of DFO’s former groundfish individual transferable quota (ITQ) survey. A primary indicator in LFA 34 is the mean number of lobsters per standard tow from this survey. The USR is defined as 80% of the median in the reference period of 1998‑99 to 2008‑09. The metric used to compare the current value to the USR is a 3-year moving average of number of lobsters per tow. No LRP has been defined.

In LFAs 35-38, a primary indicator is the mean number of lobsters per tow from certain strata from DFO’s summer research vessel (RV) survey. The USR is defined as 80% of the median catch rate for the reference period of 1985 to 2009. The metric used to compare the current value to the USR is a 3-year moving average of the number of lobsters per tow.

| Indicator | Reference points |

| Commercial catch rate (kg landed/trap haul) |

|

| Mean number of lobsters per standard tow (1 km) from the lobster trawl survey* |

|

*Formerly the ITQ survey, which began transitioning to a lobster-focused survey in 2013.

**There will be some annual variability in the USR while the survey is being developed.

| Indicators | Reference points |

| Commercial catch rate (kg landed/trap haul) |

|

| Summer RV survey (mean number of lobsters per tow in strata 490-495)** |

|

Contextual indicators

Stock assessments for each LFA also report on a number of secondary indicators. Some of the secondary indicators are ecosystem related (e.g., water temperature, predator abundance) and others capture more detailed information about the composition of the lobster stocks (e.g., sub-legal abundance and reproductive status).

Indicator of exploitation

Indicators of exploitation and removal references have not yet been determined for LFA 34 or 35‑38.

2.5 Research plan

Part of DFO’s vision is to advance sustainable aquatic ecosystems while fostering economic prosperity across maritime sectors and fisheries. The ability to provide sound advice on stock status for the management of our natural resources is largely dependent on the collaborative science programs conducted by DFO, fishing associations and academia.

DFO Science collects and assimilates the pertinent biological and fisheries information to develop and implement scientific analysis for the provision of advice to directly support decision-making and policy program delivery. In order to accomplish these goals DFO-Science conducts population monitoring programs and scientific research to develop assessments of stock status, which are used to provide advice to management for supporting the sustainable development of the resource. Quality monitoring and research programs ensure that decisions are based on the best knowledge available.

Monitoring and research are important components for management of the lobster fishery, with a long history of research results being used as primary inputs into management decisions. This monitoring, assessment and research plan (Table 10) summarizes the priorities for investment in monitoring and research in the inshore lobster fisheries for the period of 2017 to 2022.

| Strategic objectives | Themes | Monitoring, assessment and research priorities (i.e.: strategic monitoring and research needs) |

| Maintain and improve the knowledge base for the regional lobster stocks. |

Perform functions and activities critical to inform stock status. Foster and maintain monitoring and research activities in collaboration with industry stakeholders and academia. |

Collect biological and stock indicators with different long-term monitoring programs:

|

| Provision of peer reviewed science advice and scientific publications |

Develop and improve techniques for assessing stock status Investigate issues or address questions raised by clients. |

|

| Ensuring ongoing sustainability of the fishery | Continue to improve the precautionary approach framework for the lobster fishery. |

|

| Research on population dynamics and impacts of climate changes | Continue to improve on scientific knowledge (biological and physical) that can be applied to better assess the stocks. |

|

3. Social, cultural and economic importance of the fishery

3.1 Overview

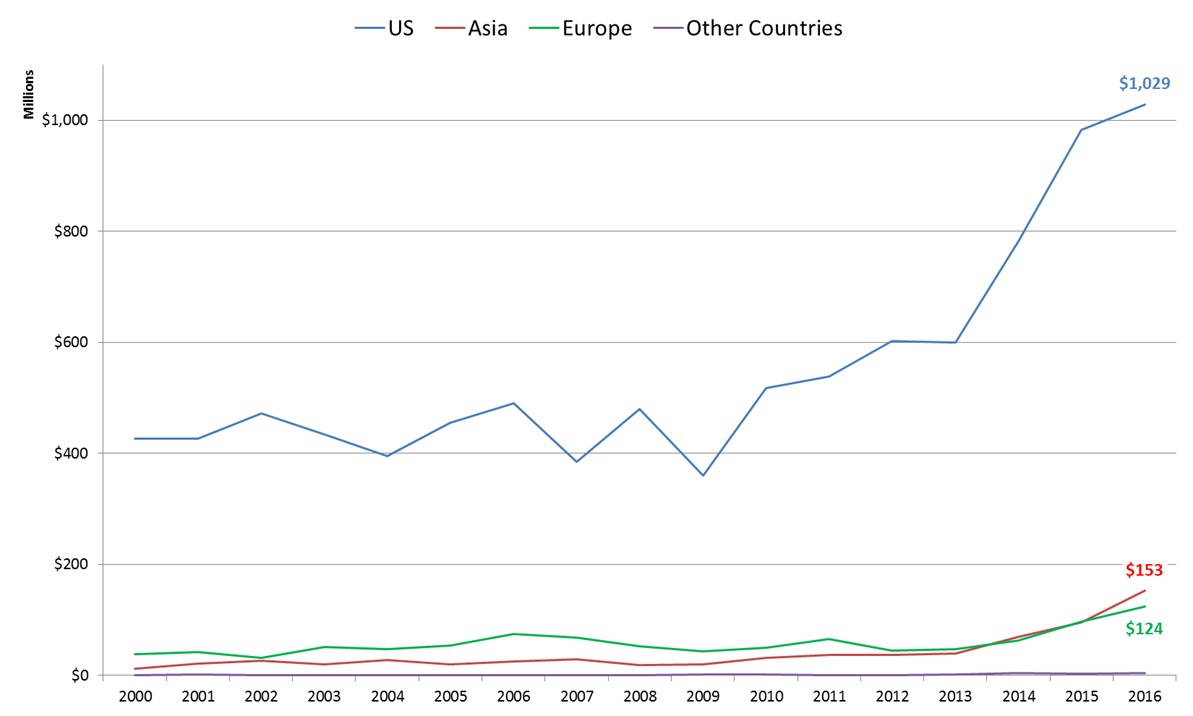

The lobster fishery² has been the backbone of the inshore commercial fishery in the Maritimes Region over the past 2 decades. In recent years, the fishery generated direct fishing employment for approximately 7,500 people and provided important economic benefits in coastal communities throughout the region, including Indigenous communities. In 2016, lobster was landed at more than 300 communities in the Maritimes Region, providing for a broad distribution of associated revenues and profits for licence holders and wages for crew.

With its long history in the region, inshore lobster represents a link for current fishing activity with the traditional social and economic life in rural Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. As an owner-operator fishery, lobster is an important contributor to the independence of the inshore fleet in Canada’s Atlantic fisheries. Inshore lobster is a key component of fisheries operations for the region’s communal commercial licence holders.

The inshore lobster fishery generates significant indirect economic benefits in the region through investment in inputs, such as vessel construction and maintenance, gear manufacture and maintenance, fuel and bait. The fishery generates significant induced economic benefits in the region as employment incomes and fishing business profits are spent and invested locally. Important economic benefits are also generated through the additional business activity that takes place post-landing, such as product handling and packing, transportation, processing, marketing and exporting. All of these activities generate additional profits and employment in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Lobster harvesting is predominantly an occupation held by men, although there are a number of female harvesters. According to 2016 Census information, the gender breakdown in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick for people working in the fish harvesting sector³ (all species) was 87.6% male and 12.4% female. The gender breakdown in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the fish processing sector4 (all species) was 52.6% male and 47.4% female.

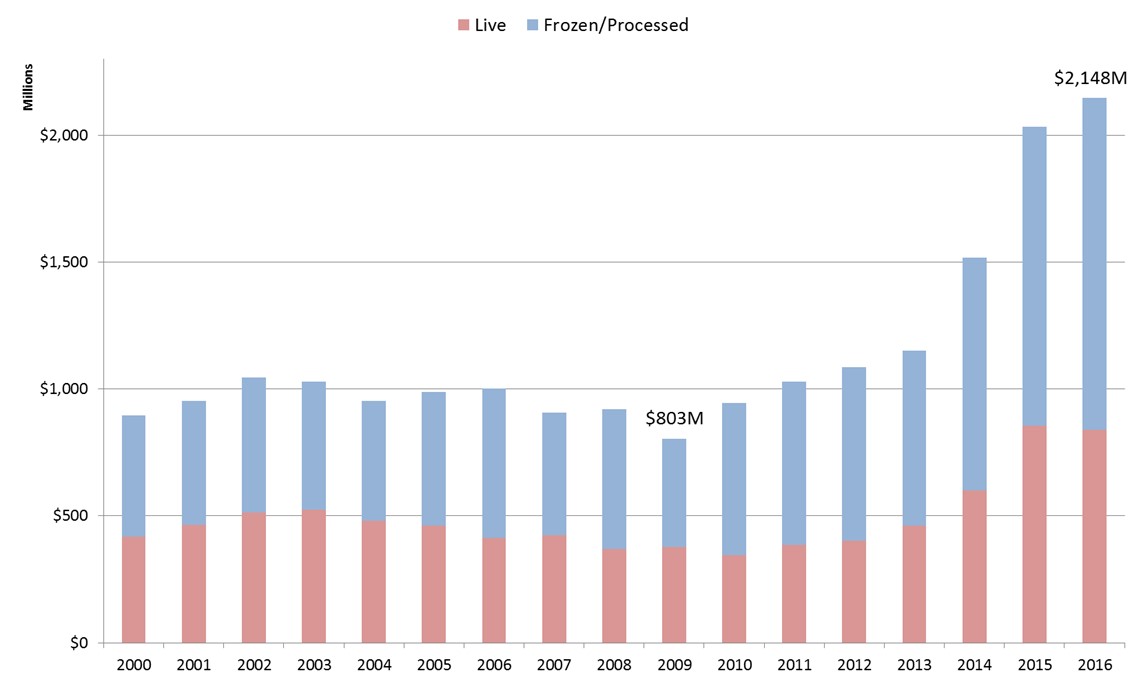

Lobster harvested by over 2,700 inshore lobster vessels in the 2015-16 season generated revenues of $876 million for commercial and communal commercial licence holders, a record for the region. The landings of inshore lobster in 2015-2016 also represented a regional record at 60,819 tonnes or just over 134 million pounds. Preliminary figures for the 2016-17 season suggest that landings and landed value were 2nd all-time highs for the region.

The Maritimes Region lobster fishery accounted for 61% of Canadian lobster landings in 2016 and was, therefore, an important supplier for Canadian exporters. Canadian exports of lobster reached a record $2.15 billion in 2016.

3.2 Lobster and the Atlantic fishery

In 2016, commercial fishery landed value for DFO Atlantic regions (Maritimes, Gulf, Quebec and Newfoundland & Labrador) totaled $3.0 billion. Maritimes Region accounted for 46% of this total and lobster accounted for 44% of the total landed value across all Atlantic regions. Within DFO Maritimes Region, lobster accounted for approximately 62% of the total landed value.

Figure 6 shows 2016 commercial landed value by DFO region and major species. Maritimes Region lobster landed value was approximately $833 million (similarly in 2017, data preliminary) and was the dominant value species in the region. Lobster was also the main value species in DFO Gulf Region.

Figure 6: Landed value by major species by DFO Atlantic region (2016).

Description

Figure 6: This chart shows the landed value of major species by DFO Atlantic region.

| Maritimes Region | Gulf Region | Quebec Region | Newfoundland & Labrador Region | Atlantic Total | Pacific Region | Canada Total | |

| Lobster | $833,536 | $369,033 | $76,303 | $36,593 | $1,315,465 | $1,315,465 | |

| Scallop | $122,768 | $1,085 | $0 | $3,528 | $127,381 | ||

| Shrimp | $79,063 | $16,307 | $48,889 | $276,064 | $420,323 | ||

| Snow crab | $80,303 | $134,966 | $111,222 | $274,011 | $600,502 | ||

| Groundfish | $96,191 | $2,249 | $18,038 | $110,393 | $226,871 | ||

| Other species | $141,216 | $28,731 | $15,939 | $88,933 | $274,819 | ||

| TOTAL | $1,353,077 | $552,371 | $270,391 | $789,522 | $2,965,361 | $351,670 | $3,317,031 |

3.3 Inshore lobster in DFO Maritimes Region

3.3.1 Regional landed weight and value5

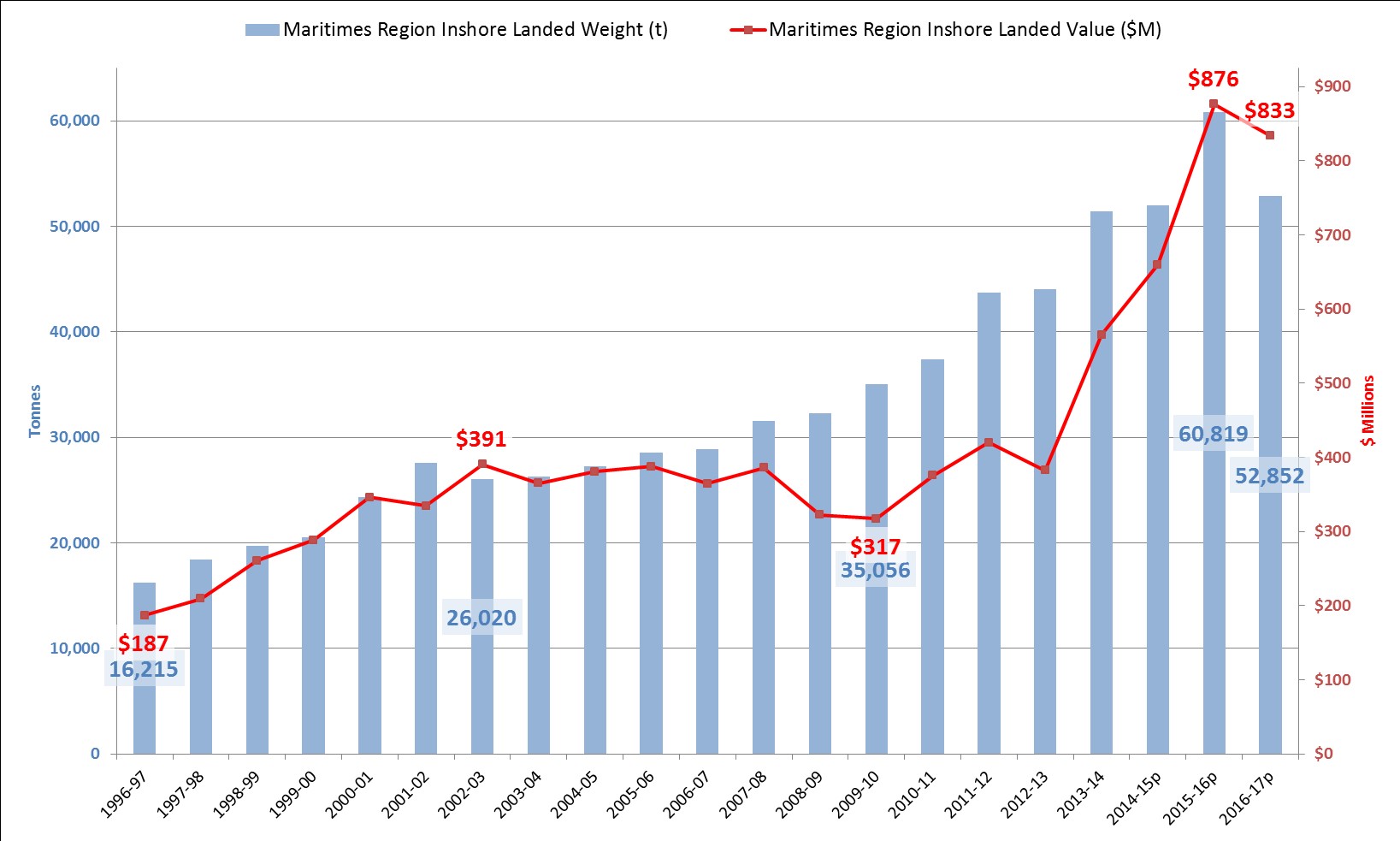

Lobster landings (as measured as landed weight) in the inshore lobster fishery in Maritimes Region rose almost uniformly year after year over the 1995-96 through 2015-16 seasons, increasing from just under 15,000 tonnes in 1995-96 to a record 60,819 tonnes in 2015-16. Preliminary landings for 2016-17 of just under 53,000 tonnes show a decline from the previous season’s peak, but still similar to the high landings levels of 2013-14 and 2014-15, which were in excess of 51,000 tonnes. From a landings perspective, 2016-17 is expected to be 2nd all-time for Maritimes Region’s inshore lobster fishery though preliminary data for 2017-18 suggest it will be above 2016-17.

The landings increase during the 2008-09 through 2012-13 period coincided with the aftermath of the global financial crisis, which saw several years of lower-than-average prices due to increased supply, a weak market and a strong Canadian dollar. By 2014-15, the market improved and the Canadian dollar weakened against the US dollar, increasing average landed prices and revenues to lobster licence holders in alignment with the historically high landings levels.

Inshore lobster nominal landed value averaged about $350 million over the 15 year period through the 2012-13 season. In just 3 years following the 2012-13 season, inshore lobster landed value more than doubled, rising dramatically from $383 million to $876 million. Preliminary figures for the 2016-17 season suggest a landed value of around $833 million and 2nd all-time high for the region.

Figure 7 shows Maritimes Region inshore lobster landed weight and landed value by season from 1995-96 to 2016-17 (preliminary). See Appendix 3 for the annual figures.

Figure 7: Maritimes Region inshore lobster landed weight and landed value.

Description

Figure 7: This chart shows Maritimes Region inshore lobster landed weight and landed value for the period 1996 to 2017, with the latest years’ data as preliminary.

| Tonnes | Maritimes (t) | Maritimes |

| Maritimes Region Inshore Landed Weight (t) | Maritimes Region Inshore Landed Value ($M) | |

| 1996-97 | 16,215 | $186.6 |

| 1997-98 | 18,400 | $209.6 |

| 1998-99 | 19,736 | $260.7 |

| 1999-00 | 20,554 | $288.2 |

| 2000-01 | 24,369 | $346.1 |

| 2001-02 | 27,549 | $334.8 |

| 2002-03 | 26,020 | $390.6 |

| 2003-04 | 26,254 | $364.8 |

| 2004-05 | 27,231 | $380.4 |

| 2005-06 | 28,523 | $387.5 |

| 2006-07 | 28,888 | $364.7 |

| 2007-08 | 31,518 | $385.7 |

| 2008-09 | 32,274 | $322.3 |

| 2009-10 | 35,056 | $317.4 |

| 2010-11 | 37,419 | $375.4 |

| 2011-12 | 43,714 | $420.0 |

| 2012-13 | 44,029 | $382.6 |

| 2013-14 | 51,408 | $565.0 |

| 2014-15p | 51,965 | $660.1 |

| 2015-16p | 60,819 | $876.0 |

| 2016-17p | 52,852 | $833.0 |

3.3.2 Landed weight and value by LFA

In Maritimes Region, inshore lobster landings (i.e. landed weight) vary by LFA based on factors, such as the relative resource abundance, the length of the fishing season and the number of licences. LFA 34 has the greatest number of inshore licences (979) and relatively high resource abundance, generating the highest overall lobster landings in the region.

Figure 8 shows the relative landings by LFA in Maritimes Region6, as well as the landings trends within each LFA from the 2007-08 season through to the 2016-17 season (data is preliminary).

Figure 8: Maritimes Region inshore lobster landed weight by LFA.

Description

Figure 8 : Ce graphique montre les prises débarquées relatives par ZPH dans la région des Maritimes, ainsi que les tendances à cet égard dans chaque ZPH, de 2007-2008 à 2016-2017 (données préliminaires).

| LFA 27 | LFA 29 | LFA 30 | LFA 31A | LFA 31B | LFA 32 | LFA 33 | LFA 34 | LFA 35 | LFA 36 | LFA 38 | LFA 38b | |

| 1996-97 | 1,290 | 40 | 80 | 50 | 98 | 247 | 1,783 | 10,645 | 738 | 681 | 551 | 0 |

| 1997-98 | 1,263 | 52 | 70 | 72 | 128 | 309 | 2,103 | 12,065 | 837 | 788 | 701 | 0 |

| 1998-99 | 1,332 | 50 | 70 | 78 | 139 | 316 | 2,129 | 13,062 | 920 | 826 | 809 | 0 |

| 1999-00 | 1,397 | 54 | 54 | 85 | 212 | 448 | 2,241 | 13,444 | 910 | 878 | 826 | 0 |

| 2000-01 | 1,716 | 66 | 98 | 102 | 204 | 433 | 2,460 | 16,190 | 1,074 | 1,032 | 989 | 0 |

| 2001-02 | 1,292 | 57 | 78 | 103 | 210 | 358 | 2,764 | 19,043 | 1,218 | 1,261 | 1,145 | 12 |

| 2002-03 | 1,540 | 125 | 73 | 152 | 279 | 389 | 2,320 | 17,613 | 1,234 | 1,155 | 1,073 | 54 |

| 2003-04 | 1,735 | 190 | 84 | 213 | 305 | 289 | 1,955 | 17,801 | 1,337 | 1,169 | 1,133 | 35 |

| 2004-05 | 1,919 | 402 | 112 | 426 | 498 | 403 | 2,519 | 17,250 | 1,172 | 1,143 | 1,363 | 15 |

| 2005-06 | 1,848 | 658 | 187 | 672 | 825 | 602 | 2,555 | 17,009 | 1,234 | 1,295 | 1,595 | 32 |

| 2006-07 | 1,914 | 792 | 216 | 827 | 1,061 | 631 | 3,033 | 16,583 | 1,191 | 1,138 | 1,413 | 80 |

| 2007-08 | 2,711 | 1,076 | 413 | 962 | 1,031 | 704 | 2,598 | 17,143 | 1,488 | 1,477 | 1,855 | 47 |

| 2008-09 | 2,072 | 1,088 | 452 | 956 | 1,270 | 829 | 3,401 | 17,262 | 1,617 | 1,596 | 1,638 | 79 |

| 2009-10 | 2,424 | 914 | 371 | 911 | 1,001 | 657 | 3,377 | 19,749 | 1,898 | 1,594 | 2,035 | 113 |

| 2010-11 | 2,542 | 727 | 383 | 757 | 925 | 758 | 3,909 | 20,401 | 2,546 | 1,916 | 2,348 | 200 |

| 2011-12 | 2,590 | 729 | 416 | 807 | 1,080 | 922 | 5,126 | 23,295 | 3,247 | 2,488 | 2,744 | 259 |

| 2012-13 | 3,588 | 607 | 461 | 671 | 740 | 862 | 5,345 | 22,770 | 3,168 | 2,739 | 2,682 | 384 |

| 2013-14 | 3,670 | 768 | 455 | 806 | 1,148 | 1,239 | 5,839 | 25,427 | 3,941 | 3,325 | 4,196 | 578 |

| 2014-15p | 3,649 | 722 | 424 | 754 | 1,036 | 1,087 | 7,071 | 24,148 | 3,723 | 3,524 | 5,045 | 766 |

| 2015-16p | 3,716 | 791 | 417 | 724 | 1,072 | 1,289 | 10,024 | 29,131 | 3,482 | 3,681 | 5,711 | 774 |

| 2016-17p | 5,250 | 874 | 580 | 841 | 1,214 | 1,238 | 8,020 | 22,684 | 3,072 | 3,382 | 4,915 | 800 |

| 2017-18p | 5,861 | 1,160 | 633 | 916 | 1,182 | 1,120 | 8,431 | 23,958 | 3,632 | 4,072 | 4,438 | 837 |

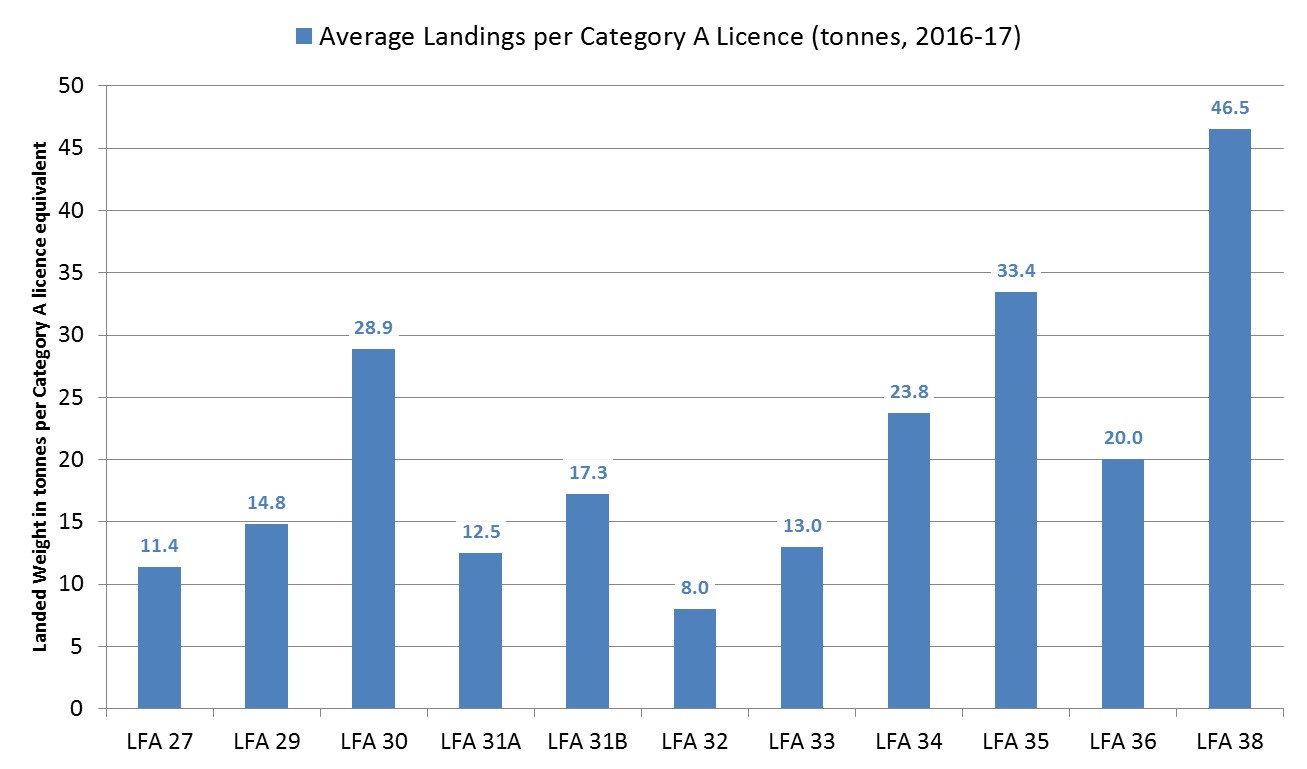

Figure 9 shows the average landed weight per licence by LFA, with the area licence count converted to Category A equivalent (i.e., partnership/stacked licences at 0.75, Category B licences at 0.30). The LFAs with the highest 2016-17 landings per licence were LFA 38, LFA 35 and LFA 30.

Figure 9: Maritimes Region inshore lobster average landed weight per licence.

Description

Figure 9: This chart shows the average landed weight per licence by LFA, with the area licence count converted to Category A equivalent (i.e., partnership/stacked licences at 0.75, Category B licences at 0.30). The LFAs with the highest 2016-17 landings per licence were LFA 38, LFA 35 and LFA 30.

| LFA 27 | LFA 29 | LFA 30 | LFA 31A | LFA 31B | LFA 32 | LFA 33 | LFA 34 | LFA 35 | LFA 36 | LFA 38 | |

| Licence Count (Category A equivalent) | 460.7 | 59.0 | 20.0 | 67.2 | 70.3 | 152.7 | 617.9 | 955.0 | 91.9 | 168.8 | 122.8 |

| Landed Weight (tonnes, 2016-17) | 5,250.0 | 874.0 | 580.0 | 841.0 | 1,214.0 | 1,238.0 | 8,020.0 | 22,684.0 | 3,072.0 | 3,382.0 | 5,715.0 |

| Average Landings per Category A Licence (tonnes, 2016-17) | 11.4 | 14.8 | 28.9 | 12.5 | 17.3 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 23.8 | 33.4 | 20.0 | 46.5 |

| Relative to 38 | 24.5% | 31.8% | 62.1% | 26.9% | 37.1% | 17.2% | 27.9% | 51.0% | 71.8% | 43.1% | 100.0% |

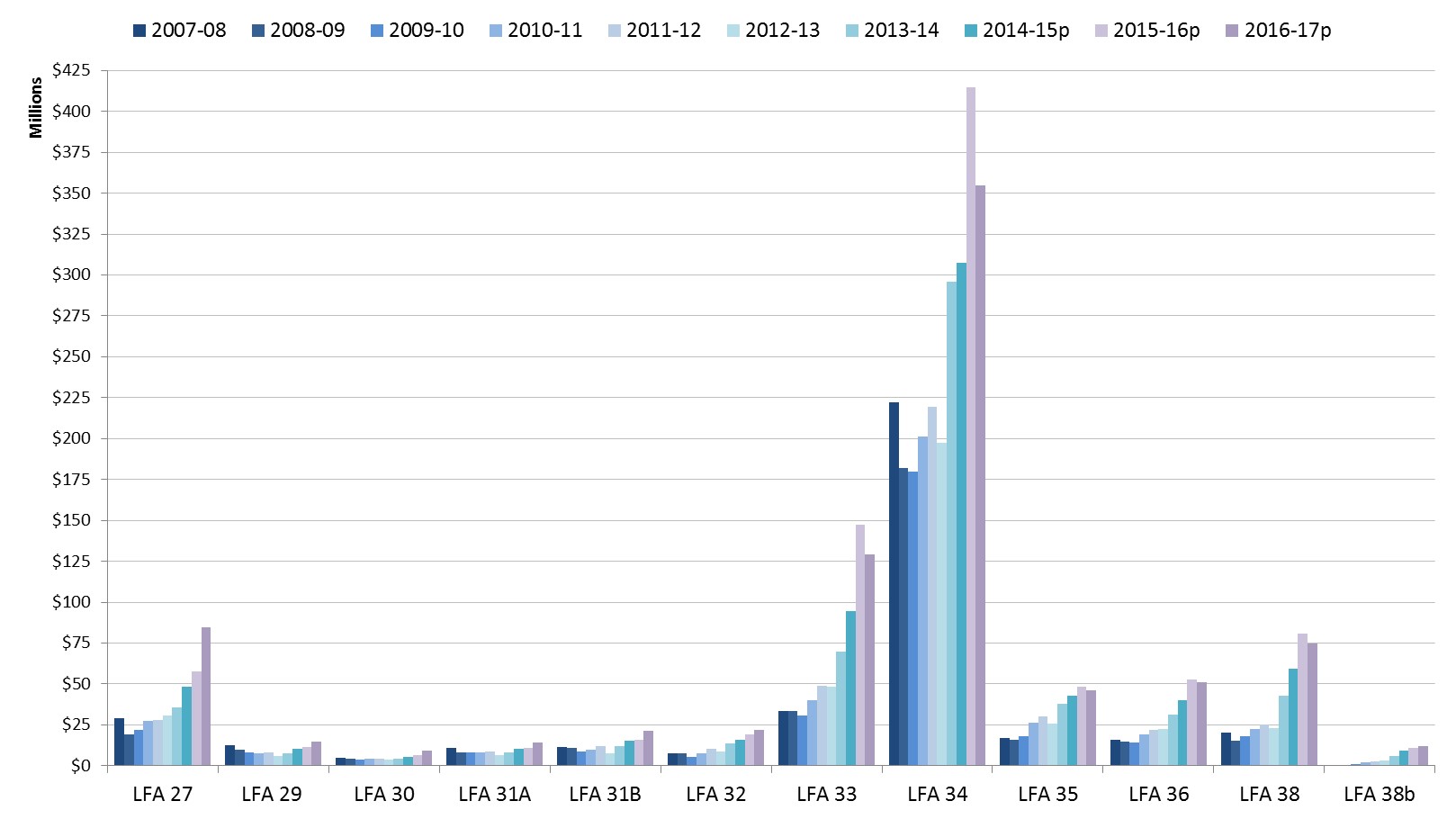

Figure 10 shows inshore lobster landed value by LFA from the 2007-08 season through 2016-17 (data is preliminary).

Figure 10: Maritimes Region inshore lobster landed value by LFA.

Description

Figure 10: This chart shows inshore lobster landed value by LFA from the 2007-08 season through 2016-17 (data is preliminary).

| LFA 27 | LFA 29 | LFA 30 | LFA 31A | LFA 31B | LFA 32 | LFA 33 | LFA 34 | LFA 35 | LFA 36 | LFA 38 | LFA 38B | |

| 2007-08 | $29,199 | $12,315 | $4,875 | $10,632 | $11,366 | $7,771 | $33,665 | $222,078 | $16,811 | $15,918 | $20,448 | $506 |

| 2008-09 | $18,988 | $9,816 | $4,483 | $8,358 | $11,060 | $7,475 | $33,513 | $182,187 | $15,999 | $14,460 | $15,363 | $486 |

| 2009-10 | $21,854 | $7,947 | $3,548 | $7,933 | $8,531 | $5,617 | $30,877 | $179,557 | $18,041 | $14,225 | $18,122 | $1,037 |

| 2010-11 | $27,574 | $7,570 | $4,331 | $7,906 | $9,491 | $7,761 | $40,018 | $201,157 | $26,388 | $18,925 | $22,386 | $1,804 |

| 2011-12 | $27,980 | $8,065 | $4,519 | $8,895 | $11,907 | $10,209 | $48,826 | $219,602 | $29,976 | $22,130 | $25,105 | $2,627 |

| 2012-13 | $30,590 | $5,828 | $3,973 | $6,292 | $7,639 | $8,499 | $48,041 | $197,505 | $25,674 | $22,264 | $22,797 | $3,410 |

| 2013-14 | $35,723 | $7,616 | $4,433 | $7,962 | $11,924 | $13,364 | $69,876 | $295,854 | $37,592 | $31,420 | $42,938 | $6,119 |

| 2014-15 | $48,357 | $10,221 | $5,596 | $10,522 | $15,123 | $15,988 | $94,745 | $307,543 | $42,851 | $40,250 | $59,378 | $9,296 |

| 2015-16p | $58,266 | $11,607 | $6,699 | $10,703 | $15,946 | $19,315 | $149,419 | $419,669 | $48,000 | $53,158 | $82,031 | $10,332 |

| 2016-17p | $84,303 | $14,436 | $9,289 | $13,945 | $21,467 | $21,929 | $129,000 | $356,000 | $45,791 | $49,854 | $74,750 | $12,134 |

3.3.3 Lobster landings by jurisdiction

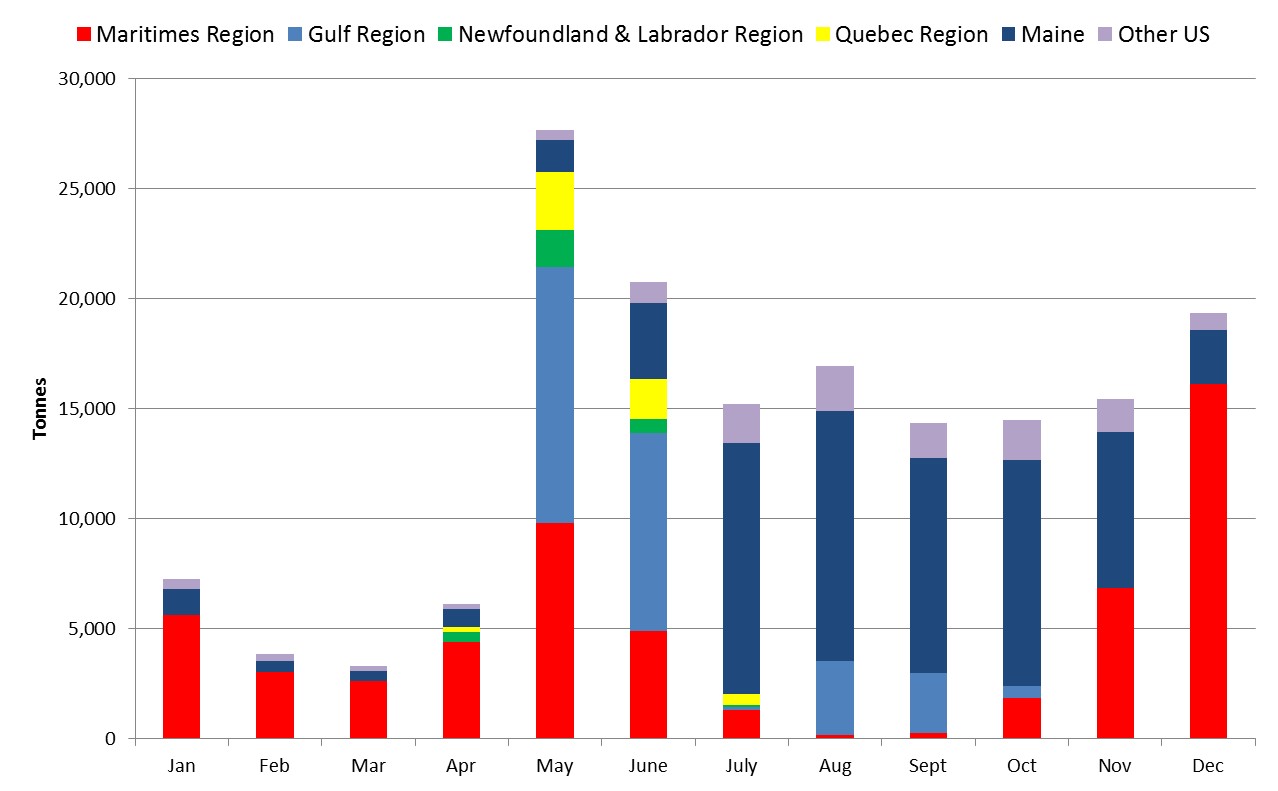

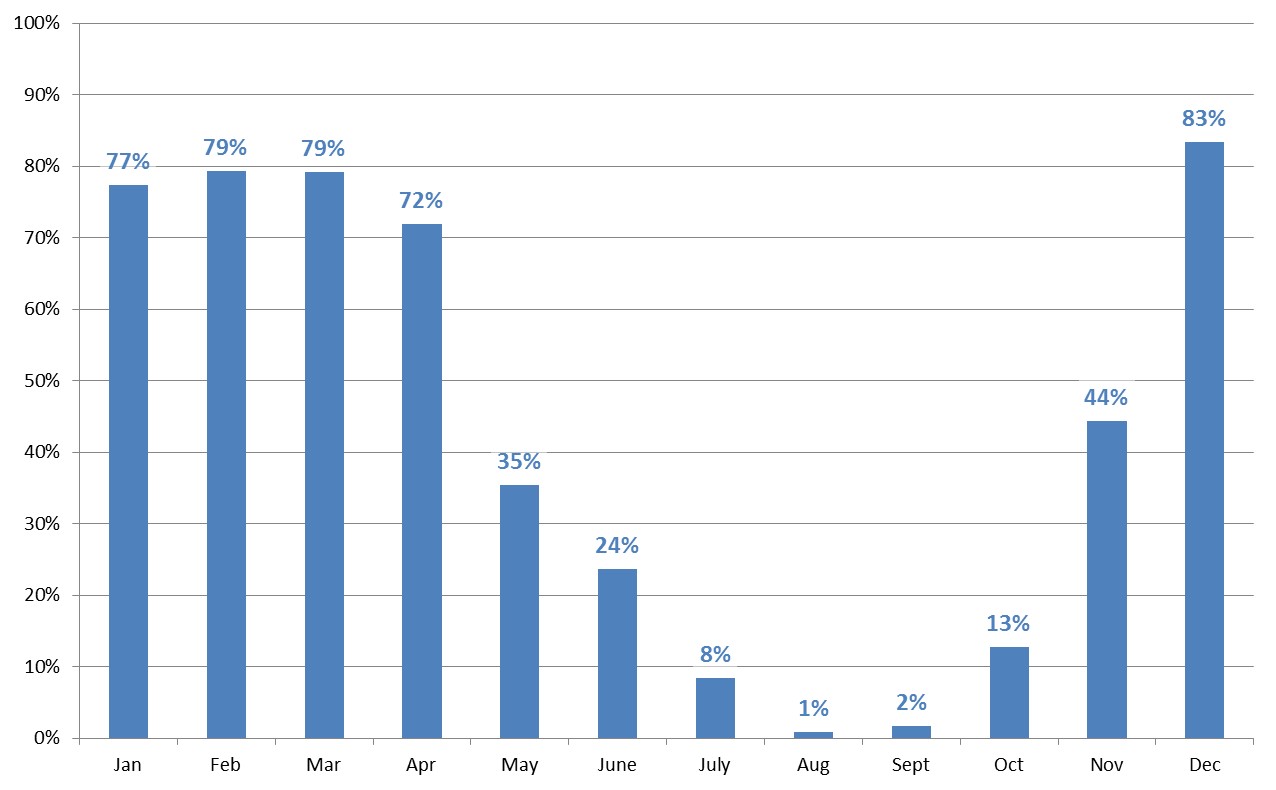

Figure 11 shows how the landings of inshore lobster in Maritimes Region during the year relate to landings in other Canadian and American management jurisdictions (2016 data). Figure 12 shows the % share of Maritimes Region inshore lobster landings relative to the total supply.

While total supply tends to be low from January through April, Maritimes Region lands the majority, between 72% and 79%, depending on the month. Some portion of sales made early in the year tend to come from lobster caught at the end of the previous year. Although landings in Maritimes Region increase in May, the share of total supply declined to 35% in 2016 and declined further to 24% in June and 8% in July. Supply from Maritimes Region in 2015 was extremely low (1-2%) in August and September via the relatively small LFA 38b fishery and the sale of lobster from harvesters’ inventory.

In October, with LFA 35 opening and fishing activity in other jurisdictions, such as Gulf Region, winding down, the Maritimes Region share increases (to 13% in October 2016). LFAs 36 and 38 open mid-November and LFAs 33 and 34 open at the end of November, bringing the Maritimes Region share for November 2016 to 44%. For December 2016, Maritimes Region accounted for 83% of lobster landings (sales), with some portion of the December catch held for sale into January of the next year.

Figure 11: North American landings of inshore lobster by jurisdiction, 2016.

Description

Figure 11: This chart shows how the landings of inshore lobster in Maritimes Region during the year relate to landings in other Canadian and American management jurisdictions (2016 data).

| 2016 Month | Landings (Sales) (t) | Maritimes Region % of Total North American Lobster Landings (Sales) (2016) | ||||||||||

| Maritimes Region | Gulf Region | Newfoundland & Labrador Region | Quebec Region | Canada Total | Maine | Other US | Maine as % of US Total | US Total | Canada + US Total | LFA 41 Portion | ||

| Jan | 5,595 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,595 | 1,176 | 461 | 71.8% | 1,637 | 7,232 | 77.4% | 69 |

| Feb | 3,032 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,032 | 490 | 302 | 61.9% | 793 | 3,825 | 79.3% | 78 |

| Mar | 2,614 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,614 | 442 | 246 | 64.3% | 688 | 3,302 | 79.2% | 97 |

| Avr | 4,380 | 0 | 455 | 240 | 5,075 | 791 | 231 | 77.4% | 1,022 | 6,097 | 71.8% | 105 |

| May | 9,784 | 11,663 | 1,676 | 2,615 | 25,739 | 1,482 | 419 | 77.9% | 1,901 | 27,639 | 35.4% | 121 |

| June | 4,894 | 9,000 | 645 | 1,801 | 16,340 | 3,455 | 933 | 78.7% | 4,388 | 20,727 | 23.6% | 191 |

| July | 1,279 | 155 | 77 | 522 | 2,032 | 11,384 | 1,779 | 86.5% | 13,162 | 15,195 | 8.4% | 108 |

| Aug | 158 | 3,367 | 0 | 5 | 3,530 | 11,363 | 2,018 | 84.9% | 13,382 | 16,911 | 0.9% | |

| Sept | 240 | 2,756 | 0 | 0 | 2,996 | 9,743 | 1,602 | 85.9% | 11,344 | 14,340 | 1.7% | |

| Oct | 1,856 | 539 | 0 | 0 | 2,395 | 10,281 | 1,794 | 85.1% | 12,075 | 14,470 | 12.8% | 19 |

| Nov | 6,826 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,826 | 7,085 | 1,497 | 82.6% | 8,582 | 15,408 | 44.3% | 45 |

| Dec | 16,117 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16,117 | 2,425 | 802 | 75.2% | 3,227 | 19,344 | 83.3% | 28 |

| 2016 Totals | 56,775 | 27,480 | 2,853 | 5,182 | 92,290 | 60,116 | 12,084 | 83.3% | 72,200 | 164,490 | 34.5% | 789 |

| 2015 Totals | 55,662 | 27,633 | 2,732 | 5,900 | 91,927 | 55,521 | 11,028 | 83.4% | 66,549 | 158,476 | 35,1% | |

| 2014 Totals | 57,336 | 28,360 | 2,138 | 5,353 | 93,187 | 56,412 | 10,706 | 84.0% | 67,119 | 160,306 | 35.8% | |

| 2013 Totals | 44,830 | 26,685 | 2,200 | 4,286 | 78,002 | 57,798 | 10,134 | 85.1% | 67,932 | 145,933 | 30.7% | |

| 2006 Totals | 31,091 | 17,279 | 2,644 | 3,241 | 54,255 | 32,962 | 8,590 | 79.3% | 41,551 | 95,807 | 32.5% | |

Figure 12: Maritimes Region monthly lobster landings (sales) as share of North American total inshore lobster landings, 2016.

Description

Figure 12: This chart shows the percentage share of Maritimes Region inshore lobster landings relative to the total supply.

| 2016 Month | Landings (Sales) (t) | Maritimes Region % of Total North American Lobster Landings (Sales) (2016) | ||||||||||

| Maritimes Region | Gulf Region | Newfoundland & Labrador Region | Quebec Region | Canada Total | Maine | Other US | Maine as % of US Total | US Total | Canada + US Total | LFA 41 Portion | ||

| Jan | 5,595 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,595 | 1,176 | 461 | 71.8% | 1,637 | 7,232 | 77.4% | 69 |

| Feb | 3,032 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,032 | 490 | 302 | 61.9% | 793 | 3,825 | 79.3% | 78 |

| Mar | 2,614 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,614 | 442 | 246 | 64.3% | 688 | 3,302 | 79.2% | 97 |

| Apr | 4,380 | 0 | 455 | 240 | 5,075 | 791 | 231 | 77.4% | 1,022 | 6,097 | 71.8% | 105 |

| May | 9,784 | 11,663 | 1,676 | 2,615 | 25,739 | 1,482 | 419 | 77.9% | 1,901 | 27,639 | 35.4% | 121 |

| June | 4,894 | 9,000 | 645 | 1,801 | 16,340 | 3,455 | 933 | 78.7% | 4,388 | 20,727 | 23.6% | 119 |

| July | 1,279 | 155 | 77 | 522 | 2,032 | 11,384 | 1,779 | 86.5% | 13,162 | 15,195 | 8.4% | 108 |

| Aug | 158 | 3,367 | 0 | 5 | 3,530 | 11,363 | 2,018 | 84.9% | 13,382 | 16,911 | 0.9% | |

| Sept | 240 | 2,756 | 0 | 0 | 2,996 | 9,743 | 1,602 | 85.9% | 11,344 | 14,340 | 1.7% | |

| Oct | 1,856 | 539 | 0 | 0 | 2,395 | 10,281 | 1,794 | 85.1% | 12,075 | 14,470 | 12.8% | 19 |

| Nov | 6,826 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,826 | 7,085 | 1,497 | 82.6% | 8,582 | 15,408 | 44.3% | 45 |

| Dec | 16,117 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16,117 | 2,425 | 802 | 75.2% | 3,227 | 19,344 | 83.3% | 28 |

| 2016 Totals | 56,775 | 27,480 | 2,853 | 5,182 | 92,290 | 60,116 | 12,084 | 83.3% | 72,200 | 164,490 | 34.5% | 789 |

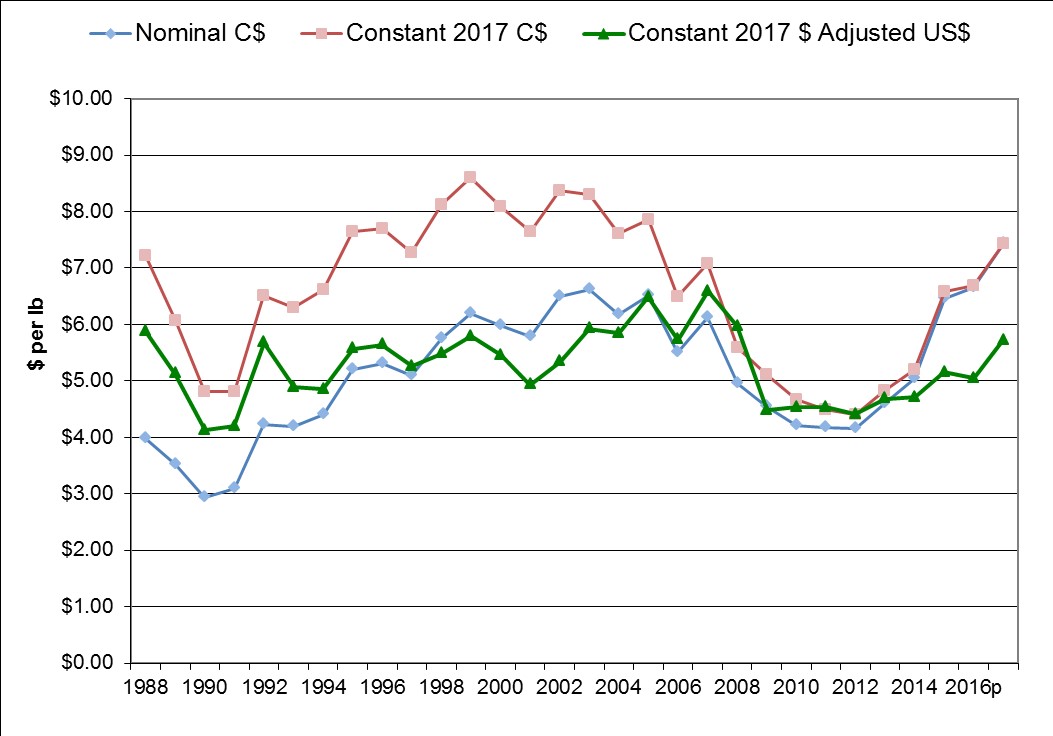

3.3.4 Average price

The average nominal inshore price for lobster in the Maritimes Region has fluctuated greatly over the period 1988 through 2017 (preliminary), reaching a low of just below $3.00 per pound in 1990 before rising to $6.62 in 2003. As lobster is considered a luxury food item, its price is relatively high among fish and seafood products, with this price appearing to be sensitive to macro-economic conditions and related changes to income levels.

Following the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, coupled with an increased supply of lobster and a stronger Canadian dollar, the average price dropped to a low of $4.16 in 2012 before rising again to an all-time high of $7.43 in 2017. The nominal price history is represented by the blue line in Figure 13.