Geoduck clam (Panopea generosa): Anatomy, Histology, Development, Pathology, Parasites and Symbionts

Normal Histology - Excretory (Heart-Kidney) System

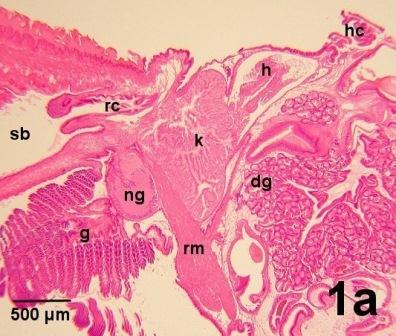

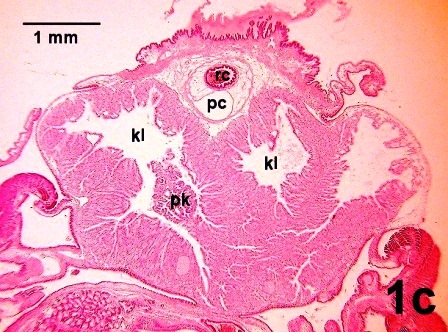

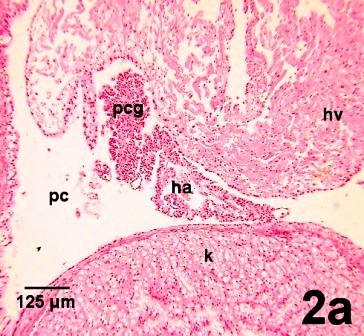

The excretory process in geoduck clams (as for most bivalves) occurs in the heart-kidney complex (Fig. 1a) which lies in the visceral mass ventral to the hinge and slightly posterior to the umbo (see anatomy sketch for location). The kidney (nephridial sacs or organs of Bajanus) can be visualised as two parallel tubes consisting of a proximal aglandular portion and distal glandular section that has collapsed into itself resulting in the two aglandular tubes being enveloped by a fused bilobed glandular section (Fig. 1b). Thus, the kidney forms a large, extensively folded gland that is located ventral to the rectum and posterior and ventral to the pericardium (Figs. 1b and c). The pericardial gland (reddish brown organ or Keber's gland) located mainly on the surface of the auricles (Fig. 2a) filters the haemolymph. The filtrate accumulates in the pericardial space from which it is drained by two short renopericardial ducts, one on each side of the body, into the kidneys. Within the kidneys, substances within the filtrate are resorbed at the apical (internal) surfaces of the kidney cells and either stored in the kidney cells or returned to the haemolymph that passes on the external surfaces of the kidney epithelium. In addition, haemocytes within the surrounding haemolymph pass on wastes to the kidney cells and these wastes are discharged into the kidney lumen by apocrine secretion (Morse and Zardus 1997). The effluent leaves the kidneys through two renopores (nephropores) which empty in common with the gonads into the mantle cavity (Martin 1983).

Figure 1a. A longitudinal view through the heart (h) and kidney (k), ventral to the hinge complex (hc) and posterior to the digestive gland (dg). Surrounding organs include the foot retractor muscle (rm), the visceral (posterior) nerve ganglion (ng), gills (g) and the rectum (rc). Effluent is released into the suprabranchial chamber (sb) of the mantle cavity and exit the geoduck clam via the excurrent channel of the siphon.

Figure 1b. An oblique cross section towards the anterior end of the heart (h) which arcs over an extension of the viscera showing a section through the rectum (rc) containing digestive wastes and the intestine (i). Ventral to the heart, the fused lobes of the distal part of the kidney (dk) surround two branches of the foot retractor muscle (rm) and contain the two aglandular proximal regions of the kidney (pk).

Figure 1c. A cross section posterior to the heart through the pericardial space (pc) that surrounds the rectum (rc) which contains digestive wastes. The large lumina (kl) in the glandular distal part of the kidney and one of the two aglandular proximal regions of the kidney (pk) are evident in this section.

Figures 1a to 1c. Histological sections of juvenile geoduck clams demonstrating the organs associated with the excretory system. The dorsal surface of each clam is at the top of each image. Haematoxylin and eosin stain.

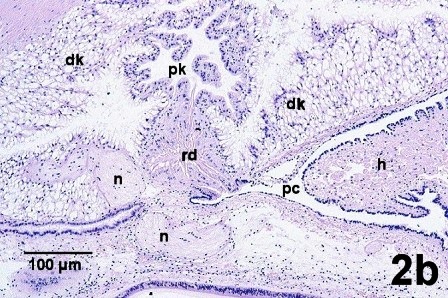

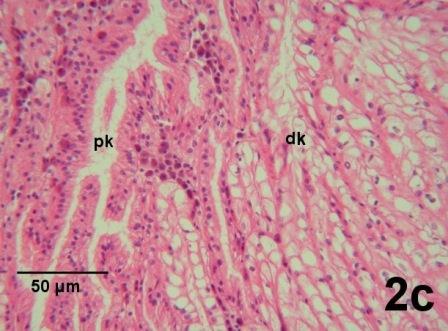

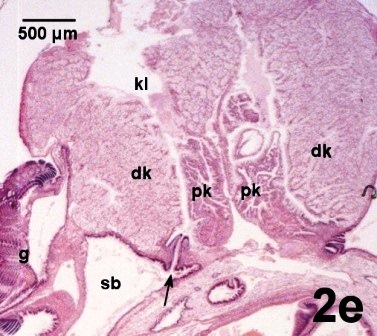

The pericardial gland consisting of podocytes (brownish in colour) is mainly associated with the surface of the auricles (right and left). The podocytes filter the haemolymph and are located on membranes that separate the haemocoel from the pericardial cavity (Fig. 2a). In the geoduck clam, the renopericardial duct, which connects the pericardial cavity to the proximal part of the kidney, is short and lined with cells bearing long cilia, (Fig 2b). The kidney consists of two components, two proximal, thinner, aglandular tubes with highly convoluted surfaces and a fused distal deeply folded glandular mass (Figs 2c and d). Typically, the proximal part of the kidney is resorptive and the distal part excretory (Andrews 1988). Effluent in the lumen of the kidney empties into the suprabranchial chamber of the mantle cavity via two nephropores (renopores, ducts), one on each side of the body, in the lateral ventral region of the kidney (Fig. 2e) and exits to the environment by way of the excurrent channel of the siphon.

Figure 2a. Podocytes (eosinophilic cells) of the pericardial gland (pcg) on the internal surface of the pericardial cavity separate the haemocoel from the lumen of the pericardial cavity (pc). Most of the podocytes are associated with the surface of the heart auricle (ha) but they are also thinly scattered on other internal surfaces of the pericardial cavity (pc) including surfaces against the heart ventricle (hv) and the kidney (k).

Figure 2b. Epithelial cells with long cilia line the internal surface of the renopericardial duct (rd) which connects the pericardial cavity (pc) surrounding the heart (h) to the aglandular proximal part of the kidney (pk) located within the glandular part of the distal kidney (dk). The renopericardial duct is adjacent to bundles of nerve fibers (n).

Figure 2c. Depiction of the morphological difference between the aglandular epithelial cells of the proximal part of the kidney (pk) and the glandular cells of the distal regions of the kidney (dk).

Figure 2d. The convoluted proximal aglandular part of the kidney (pk) is surrounded by the distal glandular part of the kidney which contains numerous channels (kc) connected to the kidney lumen (kl).

Figure 2e. The contents of the kidney lumen (kl) exit through the nephropore (arrow) into the suprabranchial chamber (sb) of the mantle cavity posterior to the gills (g). The two proximal components of the kidney (pk) are evident between the glandular tissues of the distal kidney (dk).

Figures 2a to 2e. Histological sections illustrating details of the heart-kidney complex. Haematoxylin and eosin stain.

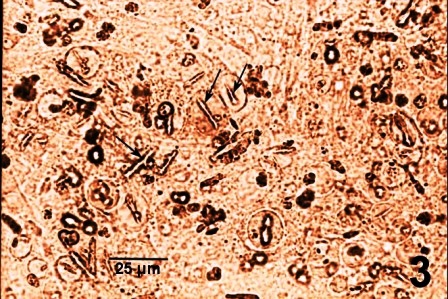

Vacuoles within some cells of the glandular distal region of the kidney contain crystal-like inclusions. These inclusions are most evident when observed in a fresh tissue preparation (Fig. 3) because they are partially soluble in the histological fixative. Presumably, these are concretions (concrements) held within lysosomal vacuoles. Secretion of the accumulated concretions occurs by apocrine discharge into the kidney lumen. Large extracellular masses formed from the concretions are carried outside the body (Morse and Zardus 1997) through the kidney openings (nephropore) into the mantle cavity (Fig. 2e).

Figure 3. An unstained wet mount squash of the glandular region of the kidney of a juvenile geoduck clam that illustrates the crystal-like inclusions (arrows), some of which appear to be in vacuoles.

A pair of muscle bands that pass through the left and right ventral regions of the kidney (labeled rm in Fig. 1b), join and continue along the posterior curve of the visceral mass (labeled rm in Fig. 1a) to the base of the foot, forming the posterior retractor muscle for the foot.

References

Andrews, E.B. 1988. Excretory Systems of Molluscs. In: The Mollusca. Volume 11, Form and Function. Edited by E.R. Trueman and M.R. Clarke. Academic Press, San Diego. pp. 381-448.

Barnes, R.D. 1968. Invertebrate Zoology, 2nd ed. W. B. Saunders Company, Toronto, 743 pp.

Eble, A.F. 2001. Chapter 4. Anatomy and histology of Mercenaria mercenaria. 4.10 Excretory system. In: Biology of the Hard Clam. Edited by J.N. Kraeuter and M. Castagna. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam. pp. 175-182.

Martin, A.W. 1983. Excretion. In: The Mollusca, Volume 5, Physiology, Part 2. Edited by A.M.S. Saleuddin and K.M. Wilbers. Academic Press, New York. pp. 353-405.

Morse, M.P. and Zardus, J.D. 1997. Bivalva. In: Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates, Volume 6A Mollusca II. Edited by F.W. Harrison and A.J. Kohn. Wiley-Liss, Inc, New York. pp. 7-118.

Quayle, D.B. 1848. Some aspects of the Biology of Venerupis pullastra (Montagu) University of Glasgow Ph. D. Thesis 1948.

Citation Information

Bower, S.M. and Blackbourn, J. (2003): Geoduck clam (Panopea generosa): Anatomy, Histology, Development, Pathology, Parasites and Symbionts: Normal Histology - Excretory (Heart-Kidney) System.

Date last revised: August 2020

Comments to Susan Bower

- Date modified: