National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas

Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Vision

- 3.0 Network Goals

- 4.0 What is a Marine Protected Area?

- 5.0 Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas

- 6.0 Bioregions for the National Network of Marine Protected Areas

- 7.0 Benefits and Costs of a Marine Protected Area Network

- 8.0 Guiding Principles

- 9.0 Network Design

- 10.0 Bioregional MPA Network Planning

- 11.0 Next Steps

- Annex 1: Glossary

- Annex 2: IUCN Guidelines

- Annex 3: Federal, Provincial and Territorial Legislation and Regulations Related to Marine Protected Areas and Related Conservation Measures

On September 1, 2011, Canada's federal, provincial and territorial members of the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers reviewed and approved in principle this National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas.

This document was prepared with the involvement of a federal, provincial and territorial Oceans Task Group ( OTG ). Members of the OTG who actively participated in development of the document represented the Governments of:

(Canada) Fisheries and Oceans Canada ( OTG co-chair); Parks Canada; Environment Canada; and, Province of British Columbia ( OTG co-chair), Province of Manitoba; Province of New Brunswick; Province of Newfoundland and Labrador; Province of Nova Scotia; Province of Ontario; Province of Prince Edward Island; Northwest Territories; Nunavut Territory; and, Yukon Territory.

Preface

The National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas (National Framework) provides strategic direction for the design of a national network of marine protected areas (MPAs) that will be composed of a number of bioregional networks. This is an important step towards meeting Canada's domestic and international commitments to establish a national network of marine protected areas by 2012. The National Framework outlines the proposed overarching vision and goals of the national network; establishes the network components, design properties, and eligibility criteria for which areas will contribute to the network; describes the proposed network governance structure; and provides the direction necessary to promote national consistency in bioregional network planning. The document has been drafted by a federal-provincial-territorial government Technical Experts Committee established by the Oceans Task GroupFootnote 1 that reports to the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers.

Consultation on the National Framework began in August 2009 and incorporated 10 weeks of web-based public review that ended in late February 2011. Comments from federal-provincial-territorial government agencies; national Aboriginal, industry and non-government organizations; academia and the public at large have been considered in preparing this final version being submitted for approval by the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers.

Figures and Tables

1. Introduction

This National Framework for Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas provides strategic direction for establishment of a national network of marine protected areas that conforms to international best practices and helps to achieve broader conservation and sustainable development objectives identified through Integrated Oceans Management and other marine spatial planning processes. Key terms used in this document are defined in the Glossary (Annex 1).

The important role of marine protected area networks in protecting marine biodiversity is reflected in a number of national and international commitments. Federally, the 1996 Oceans Act assigns responsibility to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans to lead and coordinate development and implementation of a national system (or network) of marine protected areas on behalf of the Government of Canada, within the context of integrated management of estuarine, coastal and marine environments. Canada's Oceans Strategy (2002) and the corresponding Canada's Oceans Action Plan (2005) and Health of the Oceansfunding (2007) all further committed the government to making significant progress in planning and advancing a national marine protected area network in Canada's three oceans. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada and Environment Canada each have specific but complementary mandates for establishing marine protected areas (MPAs). In 2005 the Ministers of these federal agencies released Canada's Federal Marine Protected Areas StrategyFootnote 2, which outlines how their respective marine protected area programs can collectively contribute to a network.

The provinces and territories with marine waters are important partners in marine protected area network planning. Their mandates include conservation and protection of the environment and cultural resources, natural resource management, commerce, economics, and social wellness. In some cases joint management arrangements in marine areas have also been established. In November 1992, the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers responsible for the Environment, Parks and Wildlife signed A Statement of Commitment to Complete Canada's Networks of Protected Areas, which stated: “ … in the interest of present and future generations of Canadians, Council members will make every effort to complete Canada's networks of protected areas representative of land-based natural regions, by the year 2000 and accelerate the protection of areas that are representative of marine natural regions.”

Key among other domestic and global commitments Canada has made to establishing a national network of marine protected areas are the following:

- United Nations 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity Article 8a: “Each Contracting Party shall, as far as possible and as appropriate, establish a system of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity.”

- The 1995 Canadian Biodiversity Strategy direction to: “make every effort to complete Canada's networks of protected areas representative of land-based natural regions by the year 2000, and accelerate the protection of areas that are representative of marine natural regions”.

- The 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development commitment to establish representative networks of MPAs by 2012;

- The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 2004 Program of Work on Protected Areas commitment to establish a comprehensive MPA network within an overall ecosystem approach by 2012; and

- The 2010 Conference of the Parties to the CBD commitment to a global target of “at least... 10% of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services...conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures…integrated into the wider landscape and seascape” by 2020.

2. Vision

The vision for Canada's national network of marine protected areas is: An ecologically comprehensive, resilient, and representative national network of marine protected areas that protects the biological diversity and health of the marine environment for present and future generations.

3. Network Goals

There are three goals for the national network of marine protected areas; the first one is the primary goal, the other two are secondary:

- To provide long-term protection of marine biodiversity, ecosystem function and special natural features.

- To support the conservation and management of Canada's living marine resources and their habitats, and the socio-economic values and ecosystem services they provide.

- To enhance public awareness and appreciation of Canada's marine environments and rich maritime history and culture.

4. What is a Marine Protected Area?

4.1 Definition

Canada has adopted the following International Union for the Conservation of Nature / World Commission on Protected Areas (IUCN/WCPA) 2008Footnote 3 definition of a protected area for its national network of marine protected areas:

A clearly defined geographical space recognized, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.

Details about the IUCN definition are provided in Annex 2.1. In the Canadian context, MPAs must have as their main objective the conservation of nature, and fall within IUCN categories I-VI (Annex 2.2). “Legal means” refers to federal/provincial/territorial legislative or regulatory mechanisms for establishing protected areas with a marine component (see Annex 3). “Other effective means” refers to enhanced protection achieved through non-regulatory mechanisms, such as stewardship agreements or management plans in areas owned or managed by Aboriginal or non-government organizations.

When the Spotlight on Marine Protected Areas in CanadaFootnote 4 report was released in June 2010, it illustrated that existing marine areas identified by the federal, provincial and territorial governments as protected in some manner covered approximately 56,000 km² - about 1% of Canada's oceans and Great Lakes. Not all of these protected areas will necessarily be part of the national network of marine protected areas. To be included, existing MPAs will have to meet the national marine protected area network criteria defined in Section 5.2, below.

Other marine conservation tools have the potential to contribute to MPA network goals, such as someFisheries Act closures; marine mammal management areas; critical habitat protected under the Species at Risk Act (SARA); National Historic Sites of Canada; Protected Heritage Wrecks; Designated Underwater Cultural Heritage sites; First Nations “community conserved areas”; and coastal lands owned or managed by non-government organizations like the Nature Conservancy of Canada and Ducks Unlimited Canada. However, in most cases these areas will not qualify as MPAs according to the definition indicated above.

5. Canada's Network of Marine Protected Areas

5.1 Definition

Canada has adopted the IUCN 2007Footnote 5 definition of a network of marine protected areas, namely:

A collection of individual marine protected areas that operates cooperatively and synergistically, at various spatial scales, and with a range of protection levels, in order to fulfill ecological aims more effectively and comprehensively than individual sites could alone.

5.2 Eligibility Criteria

To be considered for the national network, it must be demonstrated that a given MPA:

- Meets Canada's network definition of a marine protected area, including each of the key terms as described by the IUCN (see Section 4 and Annex 2.2); and

- Contributes to MPA network goal #1; and

- Has a management plan, or protection guidance explicitly specified in supporting legislation or regulations, and is being effectively managed for achievement of the MPA network goal(s).

5.3 Geographic scope

The geographic scope of Canada's network of marine protected areas covers tidal waters of the Canadian portion of the Arctic, Atlantic and Pacific oceans from the high-water mark outwards to the edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone, as well as the Great Lakes and any wetlands associated with those areas.

Although the Great Lakes are not truly marine, they have been described as “freshwater seas” because of their size (245,000 km² in total). They are the world's largest freshwater lake system, displaying many of the same attributes as marine environments. They connect to the Atlantic Ocean through the Saint Lawrence Seaway and other channels, linking the health of the Great Lakes to the health of the marine environment. The Great Lakes is included within the geographic scope of the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act administered by Parks Canada. Since the United States' national system of marine protected areas also includes areas established within the Great LakesFootnote 6, the overall health of Great Lakes ecosystems will benefit from domestic action and international coordination.

6. Bioregions for the National Network of Marine Protected Areas

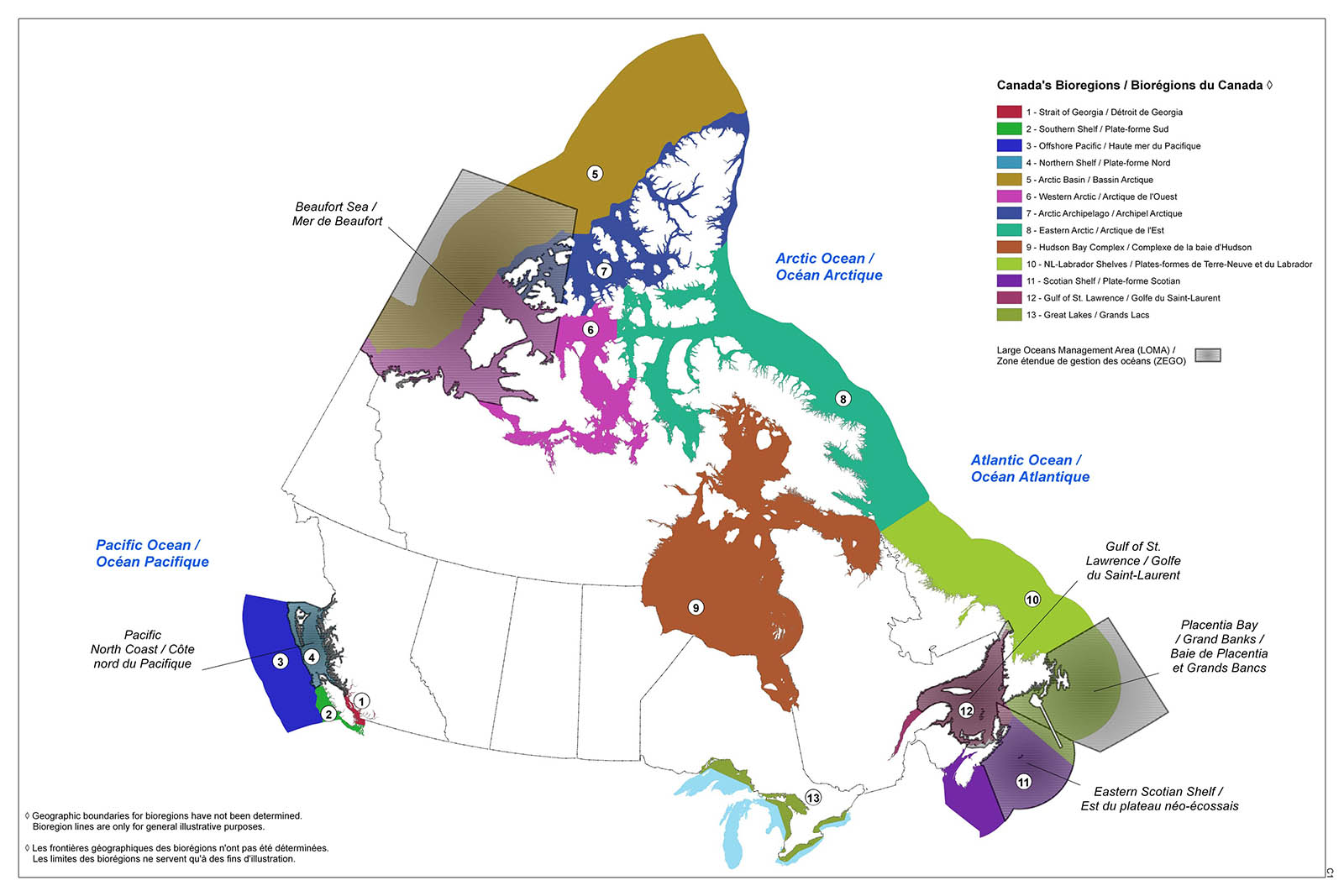

The spatial planning framework for Canada's national network of MPAs is 13 ecologically defined bioregions that cover Canada's oceans and the Great Lakes (Figure 1).

Note that the geographic boundaries for biogregions have not been determined; the bioregion lines are only for general illustrative purposes.

Network planning in these bioregions will share a common foundation—including the vision, goals, principles, eligibility criteria, design and management approach included in this National Framework. Bioregions may be subdivided into smaller planning areas, but for simplicity, the general term “bioregional network planning” is used to encompass different scales of regional planning.

The 12 oceanic bioregions were identified through a national science advisory processFootnote 7 that considered oceanographic and bathymetric similarities, important factors in defining habitats and their species.

By ocean, the marine bioregions are:

- Atlantic Ocean (3) - the Scotian Shelf (which includes the Bay of Fundy/Gulf of Maine); the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelves; and the Gulf of St. Lawrence;

- Pacific Ocean (4) - the Northern Shelf; the Strait of Georgia; the Southern Shelf; and the Offshore Pacific;

- Arctic Ocean (5) - the Hudson Bay Complex; the Arctic Archipelago; the Arctic Basin; the Eastern Arctic; and the Western Arctic.

The Government of Canada has established five Large Ocean Management Areas, or LOMAs, to advance collaborative, integrated marine planning. They are the Pacific North Coast, Beaufort Sea, Gulf of St. Lawrence, Eastern Scotian Shelf, and Placentia Bay/ Grand Banks Integrated Management Areas (Figure 1). Ecosystem health and economic development issues within the LOMA boundaries are addressed and suitably managed through comprehensive Integrated Oceans Management (IOM) governance processes (see Section 10.1). Since LOMAs were defined based on a blend of ecological and administrative considerations and pre-date the bioregions, most encompass more than one bioregion. Only the Pacific North Shelf and the Gulf of St. Lawrence bioregions generally conform to their associated LOMAs. Section 10.1 describes how LOMA governance bodies can be used to facilitate MPA network planning.

7. Benefits and Costs of a Marine Protected Area Network

Oceans and their living resources support a broad range of consumptive and non-consumptive uses ranging from renewable and non-renewable resource extraction to ecotourism. As technology evolves, new industries will also vie for ocean space. While IOM processes strive to maximize benefits to be derived from oceans while still conserving and maintaining ecological processes, marine ecosystems have a limited capacity to adjust to these increasing stresses. The role of a network of marine protected areas is to protect those areas needed to bolster ecosystem functioning so that the overall health of the ocean is not jeopardized by human uses.

7.1 Benefits

There is a wealth of scientific evidence that well managed and strongly protected individual MPAs − including those in temperate waters − can provide environmental benefitsFootnote 8. Although there are fewer studies on the effectiveness of MPA networks (since few countries have had established networks for very long), there is mounting evidence that effective networks can scale up the contribution of individual MPAs to achieve ecological benefits, which can translate into economic, social and cultural benefits.Footnote 9

With respect to ecological benefits, networks of marine protected areas can contribute by:

- Protecting examples of all types of biodiversity (both species and ecosystems);

- Helping to maintain the natural range of species;

- Facilitating the protection of unique, endemic, rare, and threatened species over a fragmented habitat;

- Enabling adequate mixing of the gene pool to maintain natural genetic characteristics of the population; and

- Facilitating the protection of ecological processes essential for ecosystem functioning, such as spawning and nursery habitats and large-scale processes (e.g., gene flow, genetic variation and connectivity), which promote an ecosystem-based approach to management.

With respect to climate change mitigation and adaptation, networks of marine protected areas can contribute by:

- Protecting habitats that capture and store carbon (i.e., coastal salt marshes, sea grasses and kelp forests);

- Protecting multiple examples of (replicating) all ecosystem types and special ecological features such as underwater canyons or critical habitats (including spawning or breeding sites), as “insurance” against catastrophic events;

- Protecting coastal ecosystems, such as wetlands, that buffer against impacts from extreme weather events;

- Providing refuge for marine species displaced by habitat change (i.e., access to similar habitat in new areas); and

- Enhancing the ecological resilience (the ability to resist or recover) of marine areas to disturbances from climate change.

There are also a number of social and economic benefits which can result from the establishment of a network of MPAs, such as:

- Sustained fisheries;

- Enhanced recreation opportunities;

- Promotion of cultural heritage;

- Enhanced planning of ocean uses, including regional coordination;

- Increased support for marine conservation;

- More effective outreach and education; and

- Enhanced research and monitoring opportunities.

There could be additional benefits where adjacent national networks of MPAs are linked (e.g., Canada/US; Canada/Denmark)Footnote 10:

- Facilitating the protection of an ecosystem or species that cannot be adequately protected in one country, such as migratory species;

- Enhancing the level of attention given to transboundary protected areas;

- Sharing effective conservation approaches across similar sites in different regions;

- Developing collaboration between neighbouring countries to address common challenges and issues; and

- Strengthening capacity by sharing experiences and lessons learned, new technologies and management strategies, and by increasing access to relevant information.

7.2 Costs

Not all ocean-based activities will necessarily be compatible with the goals of a network of marine protected areas. Several types of MPAs and other conservation measures explicitly prohibit certain classes of industrial activities (e.g., close the area to fishing or to future oil and gas development). Consequently, the establishment of a network may generate actual or potential social and economic costs, depending on the location and nature of the human activities in relation to network design/configuration. Bioregional network design processes (described in greater detail in Section 10.2) will consider opportunities to mitigate socio-economic impacts.

There is also the potential for MPA networks to offset some socio-economic impacts. In the case of the fishing industry and other industries that rely on living resources, some economic impacts may be lessened over time due to the anticipated ecological benefits of MPA networks as described above (i.e., increases in ecological resilience of the marine ecosystems should result in increased biological productivity). Other types of industries (e.g., oil and gas; renewable wind/tidal energy; shipping) that require certainty of access to particular marine areas in order to conduct their activities will benefit from the advance notice of ecologically important areas in need of protection that a network design provides.

Human use considerations come into play in the context of Integrated Oceans Management. Once an assessment of ecologically important areas has been made within a planning area, ocean managers work with activity regulators to minimize the impacts of human activities on the ecologically important areas. A risk analysis is then undertaken to determine where ecological vulnerabilities continue to occur. The most vulnerable areas tend to be those that are of greatest ecological importance yet also subject to multiple, cumulative impacts that cannot be adequately mitigated. These are the areas that can most benefit from marine protected area network planning.

In designing the network, planners may consider a range of conservation measures in order to select the most appropriate means that would complement MPAs in achieving the desired conservation goal(s). In planning a new MPA, it will be configured and sited to accommodate socio-economic considerations to the extent possible without jeopardizing achievement of the conservation goal(s).

Given that marine protected area network planning is spatial in nature, MPA network planners need to work with the full picture of socio-economic information available, and call upon the professional services of experts in cost/benefit and socio-economic impact analysis. Computer modeling tools can be used to show stakeholders and decision-makers different options or scenarios for network design, with the goal of maximizing ecological benefit and minimizing socio-economic costs. There may be areas where the ecological importance is so great that some socio-economic considerations cannot be accommodated, and conversely there may be areas of such high socio-economic significance that they are deemed inappropriate for setting aside as marine protected areas by decision-makers.

8. Guiding Principles

All stages in the development of Canada's network of marine protected areas will be guided by the following principles:

- Coherent approach. Where possible, ensure that networks of marine protected areas are linked to broader Integrated Oceans Management initiatives, including those in adjacent marine and terrestrial areas. Capitalize on the potential of established and proposed MPAs and other spatial conservation measures to achieve marine protected area network goals.

- Respect existing rights and activities:

- respect federal / provincial / territorial government mandates and authorities;

- respect relevant provisions of applicable land claims agreements and treaties; and

- take into consideration harvesting by Aboriginal groups and others, and other activities carried out in accordance with existing licenses, regulations and legal agreements.

- Ensure open and transparent processes. Employ open, transparent and inclusive processes, with opportunities for partnership, participation, consultation and timely information exchange. Enhance awareness, promote benefits, and encourage public support.

- Take socio-economic considerations into account. Once the ecological conservation needs have been identified, consider socio-economic information to achieve an optimal, cost-effective network design and also to plan individual new network MPAs.

- Apply appropriate protection measures. Ensure that the level of protection afforded is appropriate to the stated goals for the network. Network MPAs should have a high enough level of protection that ecosystems are functioning naturally and are not significantly affected by human activities.

- Conform to best management practices. Apply the precautionary approach; apply sustainable development, integrated oceans management and ecosystem-based management principles; utilize the full suite of best available knowledge (i.e., scientific, traditional, industry, community, etc.); and practice adaptive management (i.e., adjust management policies and practices on an ongoing basis in response to new ecological or socio-economic information and emerging issues with respect to network design or implementation).

9. Network Design

To meet conservation goals, Canada's national network of MPAs will be guided by network design recommendations of the international community. For example, the CBD scientific publication commonly known as the Azores ReportFootnote 11 sets out three main components of MPA network design:

- Scientific criteria for identifying Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs);

- Scientific guidance for the selection of areas to form a representative network of MPAs; and

- Recommendations for configuring networks based on additional network design properties.

The Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) housed in Fisheries and Oceans Canada has held a number of national workshops to further develop these design recommendations.Footnote 12 This science advice is being incorporated into a technical guidance companion document to this National Framework.

9.1 Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas

Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs) are spatially defined areas that provide important services - either to one or more species or populations in an ecosystem, or to the ecosystem as a whole. They meet one or more of seven criteria, as referenced in the Azores Report:

- Uniqueness or rarity (e.g., persistent polynyas (stretches of open water surrounded by ice), hydrothermal vents, seamounts);

- Special importance for life-history stages of species (e.g., breeding grounds, spawning areas, habitats of migrating species);

- Importance for threatened, endangered or declining species and/or habitats (e.g., critical habitat of species listed under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA), or similar provincial / territorial legislation);

- Vulnerability, fragility, sensitivity or slow recovery (e.g., species with low reproductive rate or slow growth; species such as corals and sponges with structures that provide benthic habitats);

- Biological productivity (e.g., estuaries, upwellings, continental margins);

- Biological diversity (areas containing comparatively higher diversity, e.g., seamounts, coral communities, sponge communities); and

- Naturalness (the selection of the more natural examples of habitats).

The Oceans Act and Fisheries Act administered by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canada Wildlife Act, Migratory Birds Convention Act and SARA administered by Environment Canada, the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act of Parks Canada and provincial/territorial protected area tools can all contribute to the protection of EBSAs.

9.2 Ecological Representation (or Representativity)

The Azores Report also gives guidance on how to include representation (referred to in the report to as “representativity”) within a network to protect biodiversity and maintain (or if necessary, restore) ecological integrity. At its most basic, broad scale, this means protecting relatively intact, naturally functioning examples of the full range of ecosystems and habitat diversity found within a given planning area such as a bioregion or Parks Canada marine region. Various jurisdictions in Canada have legislative mandates to select representative areas for protection. For example, Parks Canada has a mandate to establish a system of national marine conservation areas that are representative of the 29 marine regions identified for Canada's three oceans and Great Lakes within its system planning framework. Such representative MPAs will contribute significantly to the overall national MPA network.

In practice, an MPA network bioregion includes a number of habitat types and many species that will not be encompassed within a single large-scale representative MPA. Establishing a network of MPAs that captures examples of all habitat types within the bioregion will ensure that the finer-scale elements of biodiversity (e.g., species, communities) and physical characteristics (e.g., oceanographic conditions, bathymetry, geology) are also protected. The different habitat types in a bioregion can be identified and delineated using habitat classification schemes based on the best available physical and biological informationFootnote 13.

9.3 Additional Design Properties

To maximize the ecological benefits from protection of EBSAs and representative areas, there are additional network design properties that should be considered in configuring MPA networks. As described in the Azores Report, these properties are:

- Connectivity - ensuring that individual MPAs can benefit from each other, for example by establishing functional linkages between larval production areas and other geographically separate areas required for subsequent life stages;

- Replication - ensuring that more than one example of each ecological feature (i.e., species such as whales, fish, seabirds, invertebrates; habitats such as seamounts, banks, basins, canyons; ecological processes such as upwellings) is protected to safeguard against unexpected loss from natural events or human disturbance; and

- Adequacy/viability - ensuring that all MPAs in the network have the size and protection necessary for ecological viability and integrity. MPAs need to be large enough and sited appropriately to protect and maintain ecological processes that help to maintain biodiversity (such as nutrient flows, disturbance regimes and food-web interactions).

9.4 Culturally Important Areas

While the main objective of Canada's National Network of MPAs is conservation of nature (consistent with the MPA definition), there are many sites that are important to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal coastal communities and Canadians in general for social and cultural reasons. These areas could be considered for inclusion in the network where they are compatible with national network goals and eligibility criteria. Areas of social, cultural, or educational value include:

- Special importance for cultural heritage: an area where use of the marine environment and living marine resources are or have been of particular cultural or historical importance (e.g., for the support of traditional subsistence activities for food, social or ceremonial use; significant historical and archaeological sites, heritage wrecks);

- Public use and enjoyment: an area that offers outstanding recreational opportunities and aesthetic and/or spiritual values (e.g., sport fishing, boating, sea kayaking, diving, wildlife viewing);

- Education: an area that offers an exceptional opportunity to inform the public about the value of protecting the marine environment or to enhance awareness of particular natural and cultural features or phenomena (e.g., through outreach programs, visitor centres).

In practice, all three of these will often be achieved within a single MPA.

10. Bioregional MPA Network Planning

10.1 Governance

Governance for MPA network planning will be established at the bioregional scale, preferably using existing multi-sector Integrated Oceans Management governance structures developed within the fiveLOMAs described in Section 6. The general IOM governance model includes an executive-level oversight committee, a director-level management committee, a stakeholder advisory committee and a technical working group. MPA network planning is already encompassed within the mandates of the government agencies participating in these bodies. In some instances there are Memoranda of Understanding in place that identify conservation planning as a specific area of collaboration (e.g., between Canada and British Columbia; between Canada and Nova Scotia). For the purpose of developing a bioregional MPAnetwork, it is anticipated that a bioregional network planning team will be formed (perhaps as a sub-group of the technical working group) composed of federal and provincial/territorial government representatives working in partnership.

In the bioregions that do not have adequate IOM governance associated with them, there may be other existing governance processes to build on. In the eastern Arctic, for example, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement sets out legal requirements for governance. In the Great Lakes, the Canada-United States International Joint CommissionFootnote 14 could be approached as a potential forum for marine protected area network planning. Where there are new governance processes to work out, it will take longer to establish relationships and get underway with marine protected area network planning. Even within the bioregions that do have adequate IOM governance associated with them, it may be easier to make progress by focusing initially on network planning within the LOMAs, then expanding to the rest of the bioregion(s) in a subsequent planning phase.

Individual jurisdictions will participate in bioregional network planning within their areas of accountability and through their respective planning and reporting processes. Government agencies, Aboriginal groups, economic stakeholders (fishing, oil and gas, renewable energy, aquaculture, shipping and other industries), environmental stakeholders (e.g., non-government organizations) and other interested parties vary regionally and need to be effectively engaged from the onset of network planning. Since conservation needs already exist, processes currently underway to identify and establish new MPAs will continue while network planning gains momentum.

National MPA program coordination will be maintained in the long-term to ensure that bioregional network planning evolves with appropriate national consistency, as well as to coordinate Canada's efforts with those of the international community. National coordination encompasses information sharing on progress and best practices across the bioregions.

10.2 Planning Process for Bioregional Networks of Marine Protected Areas

Once an MPA network planning team has been struck formally by engaging the relevant federal, provincial and territorial government agencies, a process similar to the eight-step process described below could be followed, in adherence to the Guiding Principles (see Section 8), to plan the bioregional network.

- Identify and involve stakeholders and others. The planning team identifies and invites additional government bodies, Aboriginal groups, stakeholders and other interested parties to be directly involved in the planning process from the onset and throughout, building on existing governance structures and processes.

- Compile available information. Existing scientific, traditional, economic and community information for the bioregion (e.g., ecosystem and species status reports, research studies, natural resources assessments, human activity atlases, traditional use studies, and reports from consultation sessions) is compiled, analysed and geo-referenced for mapping. Knowledge gaps and science/research needs are identified.

- Set clear, measurable network objectives and conservation targets for each bioregion. Objectives for the bioregional network are identified, consistent with national MPA network goals. Consideration is given to the network objectives of adjoining bioregions to maximize synergistic effects. Conservation targets are defined to specify (and prioritize) how much of each ecological feature, function, or value needs to be protected within the network.

- Apply network design features and properties, identify areas of high conservation value and perform gap analysis. Internationally recognised network design features and properties are applied to develop a preliminary bioregional network design (see Section 9). This preliminary bioregional network design identifies multiple areas of high conservation value that collectively satisfy the network objectives and conservation targets. Conservation planning software may be employed at this stage to optimize network design from an ecological perspective. A gap analysis is then undertaken to determine where existing MPAs and other protection measures overlap with priority areas and where new MPAs or other conservation tools are needed in order to complete protection within the bioregional network. The gap analysis should identify where existing protection measures fall short and if there is any overlap or duplication in current protection. Network design is an iterative process that continues in the next step.

- Consider potential economic and social impacts; finalize network design. In the determination of where MPAs and other conservation tools are needed, seek to understand and minimize potential economic and social consequences. However, flexibility in placement of an MPA will not always be possible (e.g., unique habitats such as underwater canyon or hydrothermal vent). Conservation planning software may be employed again at this stage to support discussions with stakeholders and the public and inform decision-making. The software can produce different MPA network scenarios (e.g., by altering targets) that allow people to visualize possible network designs. Design of the network is finalized.

- Finalize a bioregional network action plan that includes the network sites, appropriate conservation measures and responsible authorities. Bioregional network planners and partners identify priorities for action and the specific network gaps that their individual mandates allow them to address. A bioregional network of marine protected areas action plan for moving forward is finalized. The network action plan should include estimated budget and resource requirements. The action plan could also identify ecologically meaningful targets for the percent of a bioregion to be protected by a specific date.

- Undertake site-specific planning and implementation. Bioregional network planners and partners develop new conservation measures, including MPAs, according to the bioregional network action plan and their individual priorities and resources. Seek to understand and minimize potential economic and social consequences at the site-specific level (i.e., zoning and other management approaches can be applied to respond to socio-economic concerns), using existing information. Public involvement is an essential element of this step.

- Manage and monitor the MPA network. Once the network starts to take shape, ongoing research, monitoring and adaptive management will be needed to ensure management practices are achieving network goals and objectives. This monitoring should be above and beyond monitoring that takes place at the site level. Reporting to Canadians on the effectiveness of bioregional networks of marine protected areas in achieving their stated goals and objectives will occur routinely.

11. Next Steps

Best practices for implementing this National Framework and proceeding with bioregional network planning need to be elaborated on through federal-provincial-territorial collaboration and consultative processes. This documentation will help to bring consistency to the overall national network of marine protected areas. Since Canada has had limited experience with marine protected area network planning, the technical guidance will be developed through practice as well as through science advice. While the aim is to have an overall blueprint, technical guidance and some initial action plans or bioregional network designs for Canada's network of marine protected areas in place by 2012, developing the remaining action plans and populating the network with new areas will be incremental over time as resources allow.

Annex 1: Glossary

- Adaptive management

- A systematic process for continually improving management policies and practices by learning from the outcomes of previously employed policies and practices.

- Bathymetric

- Pertaining to measurement of the depth of water in oceans or lakes.

- Biological diversity

- The full range of variety and variability within and among living organisms and the ecological complexes in which they occur; the diversity they encompass at the ecosystem, community, species and genetic levels; and the interaction of these components.

- Biological productivity

- The production of plant and animal matter; nature's ability to reproduce and regenerate living matter.

- Bioregion

- A biogeographic division of Canada's marine waters out to the edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone, and including the Great Lakes, based on attributes such as bathymetry, influence of freshwater inflows, distribution of multi-year ice, and species distribution.

- Bioregional network planners

- The federal, provincial and territorial government agencies in a given bioregion that have authority to establish MPAs or administer lands, regulate activities, etc., that are of direct relevance to MPA planning, plus any other parties that have mechanisms for protecting areas.

- Community knowledge

- Knowledge or expertise held by communities (e.g., fishing community), characterized by common or communal ownership.

- Conservation

- The maintenance or sustainable use of the Earth's resources in order to maintain ecosystem, species and genetic diversity and the evolutionary and other processes that shape them (CBD 1992). In the context of the IUCN definition of an MPA, conservation refers to the in situmaintenance of ecosystems and natural and semi-natural habitats and of viable populations of species in their natural surroundings.

- Ecological resilience

- Ability of a system to undergo, absorb and respond to change and disturbance whilst maintaining its functions and controlsFootnote 15.

- Ecosystem approach

- A strategy for the integrated management of land, water and living resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way (CBD 2004).

- Ecosystem integrity

- Refers to the degree to which a given area (potential MPA) functions as an effective, self-sustaining ecological unit. MPAs should be designed at an ecosystem level, recognizing patterns of connectivity within and among ecosystems. In general, an MPA which is designed to protect a diverse array of habitat types will also conserve the ecological processes and integrity of the ecosystemFootnote 16.

- Ecosystem services

- The benefits people obtain from ecosystems, including provisioning services such as food and water; regulating services such as regulation of floods, drought, land degradation, and disease; supporting services such as soil formation and nutrient cycling; and cultural services such as recreational, spiritual, religious and other nonmaterial benefits (from IUCN definition of a protected area, 2008).

- Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

- An area of the sea stretching from the seaward edge of the territorial sea out to 200 nautical miles from the coast, within which a country has sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving and managing living and non-living resources of the water, sea-bed and subsoil. [Where the territorial sea is defined as an area of the sea extending 12 nautical miles from the coast.]Footnote 17

- Integrated Oceans Management (IOM)

- A continuous process through which decisions are made for the sustainable use, development and protection of areas and resourcesFootnote 18.

- Large Ocean Management Area (LOMA)

- One of five marine areas established by the Government of Canada as pilots for Integrated Oceans Management planning. Each LOMA is typically hundreds of square kilometres in size.

- Marine (in the context of Canada's national network of MPAs)

- Canada's oceans estate extending to and including the Great Lakes, from the high water mark in coastal or shoreline areas to the outer edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone.

- MPA authorities

- The individual federal-provincial-territorial jurisdictions that have specific mandates and objectives for establishing MPAs.

- Precautionary approach

- A management approach which recognizes that the absence of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing decisions where there is a risk of serious or irreversible harm.

- Protection

- Any regulatory or other provision to reduce the risk of negative impact of human activities on an area.

- Sustainable development

- Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needsFootnote 19.

- Sustainable use

- The use of components of biological diversity in a way and at a rate that does not lead to the long-term decline of biological diversity, thereby maintaining its potential to meet the needs and aspirations of present and future generations" (1995 Canadian Biodiversity Strategy).

- Traditional Knowledge

- Knowledge gained from generations of living and working within a family, community or culture (1995 Canadian Biodiversity Strategy).

Annex 2: IUCN Guidelines

2.1 Key elements of the IUCN definition of a marine protected area

Key elements of the IUCN definition of a protected areaFootnote 20 are listed and described below.

- Clearly defined

- implies a spatially defined area with agreed and demarcated borders. These borders can sometimes be defined by physical features that move over time (e.g., river banks) or by management actions (e.g., agreed no-take zones).

- Geographical space

- includes land, inland water, marine and coastal areas or a combination of two or more of these. “Space” has three dimensions, e.g., as when the airspace above a protected area is protected from low-flying aircraft or in marine protected areas when a certain water depth is protected or the seabed is protected but water above is not: conversely subsurface areas sometimes are notprotected (e.g., are open for mining).

- Recognized

- implies that protection can include a range of governance types declared by people as well as those identified by the state, but that such sites should be recognised in some way (in particular through listing on the World Database on Protected Areas - WDPA).

- Dedicated

- implies specific binding commitment to conservation in the long term, through, e.g., international conventions and agreements; national, provincial and local law; customary law; covenants of non-government organizations; private trusts and company policies; and certification schemes.

- Managed

- assumes some active steps to conserve the natural (and possibly other) values for which the protected area was established; note that “managed” can include a decision to leave the area untouched if this is the best conservation strategy.

- Legal or other effective means

- means that protected areas must either be gazetted (that is, recognised under statutory civil law), recognised through an international convention or agreement, or else managed through other effective but non-gazetted, means, such as through recognised traditional rules under which community-conserved areas operate or the policies of established non-governmental organisations.

- To achieve…

- implies some level of effectiveness. Although the category will be determined by objective, management effectiveness will progressively be recorded on the World Database on Protected Areas and over time will become an important contributory criterion in identification and recognition of protected areas.

- Long-term

- protected areas should be managed in perpetuity and not as short term or a temporary management strategy.

- Conservation

- refers to the in situ maintenance of ecosystems and natural and semi-natural habitats and of viable populations of species in their natural surroundings.

- Nature

- always refers to biodiversity, at genetic, species and ecosystem level, and often also refers to geodiversity, landform and broader natural values.

- Associated ecosystem services

- ecosystem services that are related to but do not interfere with the aim of nature conservation (e.g., provisioning services such as food and water; regulating services such as regulation of floods, drought, land degradation, and disease; supporting services such as soil formation and nutrient cycling; and cultural services such as recreational, spiritual, religious and other nonmaterial benefits).

- Cultural values

- includes those that do not interfere with the conservation outcome (all cultural values in a protected area should meet this criterion), including in particular those that contribute to conservation outcomes (e.g., traditional management practices on which key species have become reliant) and those that are themselves under threat.

2.2 Summary of IUCN protected area management categories and their use in evaluating marine protected areas

The 2008 IUCN document also includes a full description of each of the six categories of protected area management. Brief summaries of these descriptions are given below.

- Category Ia

- Strictly protected areas set aside to protect biodiversity and also possibly geological/ geomorphological features, where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values. Such protected areas can serve as indispensable reference areas for scientific research and monitoring.

- Category Ib

- Usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.

- Category II

- Large natural or near natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities.

- Category III

- Set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, sea mount, submarine cavern, geological feature such as a cave or even a living component such as a specific coralline feature. They are generally quite small protected areas and often have high visitor value.

- Category IV

- Aim to protect particular species or habitats and management reflects this priority. Many category IV protected areas will need regular, active interventions to address the requirements of particular species or to maintain habitats, but this is not a requirement of the category.

- Category V

- Areas where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character with significant ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value: and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values.

- Category VI

- Conserve ecosystems and habitats, together with associated cultural values and traditional natural resource management systems. They are generally large, with most of the area in a natural condition, where a proportion is under sustainable natural resource management and where low-level non-industrial use of natural resources compatible with nature conservation is seen as one of the main aims of the area.

Annex 3: Federal, Provincial and Territorial Legislation and Regulations Related to Marine Protected Areas and Related Conservation Measures

Table 1. Federal/provincial /territorial legislation or regulation under which protected areas or related marine management measures are established (current as of April 2011)

In keeping with Guiding Principle #2, MPAs should be established in a manner consistent with applicable land claims agreements and treaties, not listed in this Annex.

| Legislation / Regulation | Type of Area | Department/Agency | Purpose |

| FEDERAL GOVERNMENT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oceans Act, 1996, c.31 | Oceans Act Marine Protected Area (OAMPA) | Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) | To conserve and protect fish, marine mammals, and their habitats; unique areas; areas of high productivity or biological diversity |

| Fisheries Act, 1985, c.43 | Fishery closure | As above | To conserve and protect fish and fish habitat; to manage inland fisheries (among other purposes) |

| Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act, 2002, c. 18 | National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA) | Parks Canada Agency (PC) | To conserve and protect representative examples of Canada's natural and cultural marine heritage and provide opportunities for public education and enjoyment |

| Canada National Parks Act, 2000, c.32 | National Park | As above | To protect representative examples of Canada's natural heritage for the benefit, education and enjoyment of Canadians |

| Canada Wildlife Act, R.S., 1985, c. W-9 | National Wildlife Area (NWA) | Environment Canada (EC) | To conserve and protect habitat for a variety of wildlife, including migratory birds and species at risk |

| Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 | Migratory Bird Sanctuary (MBS) | As above | To conserve and protect habitat for migratory bird species |

| Species at Risk Act, 2002 | Protected critical habitat | DFO, PC and EC | To protect and recover wildlife species at risk in Canada |

| Canada Shipping Act, 2001, art 136. (1), f) | Vessel Traffic Services Zone | Transport Canada | To regulate or prohibit the navigation, anchoring, mooring or berthing of vessels for the purposes of promoting the safe and efficient navigation of vessels and protecting the public interest and the environment |

| BRITISH COLUMBIA (BC) | |||

| Park Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 344 | Park | Ministry of the Environment | To protect representative ecosystems, and special natural, cultural and recreation features; and to provide outdoor recreation in natural environments for the inspiration, use and enjoyment of the public |

| As above | Conservancy | As above | Conservancies are set aside for protection of biological diversity, natural environments and recreational values, and the preservation and maintenance of First Nations' social, ceremonial and cultural uses |

| Ecological Reserve Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 103 | Ecological Reserve | As above | Reserve Crown land for ecological purposes, including areas suitable for research and education, that are representative of natural ecosystems in British Columbia, that are examples of modified environments that can be studied for their recovery, and that are habitats of rare, endangered or unique species. |

| Environment and Land Use Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 117 | Protected Area | As above | To protect representative examples of: ecosystems; recreational and cultural heritage; and special natural, cultural heritage and recreational features |

| Land Act | Designated Wildlife Reserve | Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations | Sensitive habitat or habitat important for the conservation or well-being of species may be protected for specified time periods (e.g. 5-60 years), often as an interim measure before their ultimate establishment as a wildlife management area |

| Wildlife Act 2003 | Wildlife Management Area | As above | To conserve and protect fish, wildlife and their habitats |

| MANITOBA (MB) | |||

| The Provincial Parks Act, C.C.S.M., c. P-20 | Provincial Park | Manitoba Conservation | Purpose depends on park type: wilderness parks preserve natural landscapes; heritage parks preserve human / cultural resources; natural parks preserve natural landscapes and accommodate recreation and resource use; recreation parks provide outdoor recreation |

| As above | Park Reserve | As above | Park reserve status is used to temporarily protect (up to 5 years) an area being considered for full protected area status |

| The Ecological Reserves Act, C.C.S.M., c. E-5 | Ecological Reserve | As above | Preserve unique and rare natural (biological and geological) features of the province; provide for ecosystem and biodiversity preservation, research, education and nature study |

| The Wildlife Act, C.C.S.M., W130 | Wildlife Management Area | As above | Wildlife Management Areas exist for the benefit of wildlife and for the enjoyment of people; they play an important role in biodiversity conservation and provide for a variety of wildlife-related forms of recreation (often including hunting and trapping) |

| The Forest Act, C.C.S.M., F150 | Provincial Forest | As above | Protection of ecologically significant forest landscapes |

| ONTARIO (ON) | |||

| Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act 2006 | Provincial Park | Ministry of Natural Resources | Permanent protection of a system of provincial parks and conservation reserves that includes ecosystems that are representative of all of Ontario's natural regions; protects provincially significant elements of natural and cultural heritage; maintains biodiversity; and provides opportunities for compatible, ecologically sustainable recreation |

| As above | Conservation Reserve | As above | As above |

| Wilderness Areas Act 1990 | Wilderness Area | As above | Protection; intended to protect the natural state of a specific area |

| QUEBEC (QC) | |||

| Natural Heritage Conservation Act, R.S.Q. c.C-61.01 |

Aquatic reserves | Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs | Protect all or part of a body of water or watercourse, including associated wetlands, because of the exceptional value it holds from a scientific, biodiversity-based viewpoint, or to conserve the diversity of its biocenoses or biotopes |

| As above | Biodiversity reserves | As above | Maintain biodiversity and in particular an area established to preserve a natural monument — a physical formation or group of formations — and an area established as a representative sample of the biological diversity of the various natural regions of Québec |

| Parks Act, R.S.Q. 1977, c. P-9 | National Parks (conservation / recreation) | As above | National parks in Quebec are actually provincial parks protected for conservation and recreation uses. Federally protected National Parks exist in Quebec but are referred to as National Parks of Canada |

| Ecological Reserves Act, R.S.Q. 1977, c. R-26.1 | Ecological Reserves | As above | Conserve habitat in a natural state; reserve habitats of scientific, and in some cases educational, interest; and protect threatened or vulnerable species of plants and wildlife |

| An Act respecting the Saguenay - St. Lawrence Marine Park | Saguenay - St. Lawrence Marine Park | As above | Specifically for protecting the designated area of the Saguenay - St. Lawrence encompassed in this protected area |

| An Act respecting the conservation and development of wildlife | Waterfowl Gathering Areas | As above | Protection of habitat specifically for waterfowl, 352 of which include intertidal or subtidal components |

| NEW BRUNSWICK (NB) | |||

| Parks Act, S.N.B 1982, c. P-2.1 | Provincial Parks | New Brunswick Tourism; Department of Natural Resources | Provincial parks include areas protected as recreational parks, campgrounds, beaches, wildlife parks, picnic grounds, resource parks or reserves. Primarily managed by Department of Tourism |

| Protected Natural Areas Act (replaced: Ecological Reserves Act) | Protected Natural Areas (class 1) | As above | Lands and waters permanently set aside for conservation of biological diversity. All activities are prohibited except by permit from DNR |

| see above | Protected Natural Areas (class 2) | As above | Areas permanently set aside for the conservation of biological diversity, where certain recreational activities having minimal impact will be allowed |

| Crown Lands and Forests Act | N/A | As above | Legislative basis for the development, utilization, protection, and integrated management of Crown land resources, including access and recreation on Crown lands as well as rehabilitation of Crown lands |

| NOVA SCOTIA (NS) | |||

| Wilderness Areas Protection Act, S.N.S. 1998, c. 27 | Wilderness Areas | Department of Environment | Protect typical examples of Nova Scotia's natural landscapes, biological diversity, and wilderness recreation activities |

| Provincial Parks Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c. 367 | Provincial Parks | Department of Natural Resources | Protection of land for wilderness recreation and ecological preservation |

| Special Places Protection Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c. 438 | Protected Sites/Nature Reserves | Department of Tourism, Culture & Heritage/ Department of Environment | Protect areas of archeological or historical significance/ areas of ecological significance |

| Beaches Act | Protected Beaches | Department of Natural Resources | Protects designated beaches and their associated dune systems and regulates and controls land-use activities on the beach that may negatively impact the beach ecosystem |

| Conservation Easements Act | Conservation Easements | Department of Natural Resources | Designated organizations may hold conservation easements granting rights and privileges over the owner's land for the purposes of protecting, restoring or enhancing areas of ecological or archaeological significance |

| Wildlife Act | Wildlife Management Areas | Department of Natural Resources | Wildlife Management Areas exist for the benefit of biodiversity conservation, wildlife habitat protection and management, and for the enjoyment of people; they play an important role in biodiversity conservation and provide for a variety of wildlife-related forms of recreation (often including hunting and trapping); allowable activities are described in regulation |

| PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND (PEI) | |||

| Natural Areas Protection Act, R.S.P.E.I. 1988, c. N-2 | Natural Areas | Department of Environment, Energy and Forestry | Protection of ecologically significant sites including sand dunes, marshes, offshore islands, marine areas |

| Wildlife Conservation Act | Wildlife Management Areas | As above | Protection of wildlife habitat |

| Recreation Development Act, R.S.P.E.I. 1988, c. R-8 | Provincial Parks | Department of Tourism and Culture | Legislation that can be used to create Provincial Parks, supports and provides direction for the management of Provincial Parks, clarifies activities that are permitted / prohibited in these parks, can protect beaches. These Parks are primarily protected for the purpose of Tourism and recreation |

| NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR (NL) | |||

| Wilderness and Ecological Reserves Act, R.S.N. 1990, c. W-9 | Wilderness / Ecological Reserves | Department of Environment and Conservation | Protection of natural heritage and biodiversity and provide opportunities for learning, research and recreation |

| Provincial Parks Act, R.S.N. 1990, c. P-32 | Provincial Parks | As above | Protect the natural environment including flora and fauna through promotion of conservation and prohibiting certain activities such as hunting and resource harvesting |

| Wild Life Act,RSNL 1990 Chapter W-8 | Wildlife Reserves | Department of Environment and Conservation | An area set aside for protection, preservation or propagation of wildlife through restrictions on activities such as fishing |

| Endangered Species Act, SNL 2001 Chapter E-10.1 | Recovery and Critical Habitat | As above | Legislation is not specifically designed to create protected areas but it can prescribe land-use activities and has implications for the establishment and management of protected areas |

| Lands Act, SNL 2001 Chapter 36 | Crown Reserves | Department of Environment and Conservation | S.8 of the Lands Act allows the minister to create a reserve up to 100ha. Reserves over 100ha must be approved by the Lieutenant-Governor in Council. Crown land is then set aside for a specific purpose and is referred to as alienated crown land. |

| As above | Special Management Areas (SMAs) | As above | S.57 of the Lands Act allows the Lieutenant-Governor in Council to grant temporary or permanent protection to an area - declare an SMA. S.58 allows administration and control of the SMA to be designated to the minister of another department. |

| Water Resources Act,SNL 2002 cW-4.01 | N/A | Department of Environment and Conservation | Legislation is used to ensure the continuing availability of clean water for the environmental, social and economic well-being of the province. Provisions under this act can have positive implications towards conservation of coastal and marine areas |

| YUKON TERRITORY (YT) | |||

| Parks and Land Certainty Act, S.Y. 2001, c. 46 | Ecological reserves | Department of Environment | Protect unique natural / ecological areas or habitat for rare plants or animals |

| As above | Natural Environment parks | As above | Protect representative / unique landscapes |

| As above | Wilderness Preserves | As above | Protect an ecological unit in it's natural state e.g. watershed |

| As above | Recreation Parks | As above | Provide outdoor recreation / education opportunities |

| As above | Special Management Areas | As above | Protected areas established within a Traditional Area of a Yukon First Nation under a final agreement |

| Wildlife Act | Habitat Protection Areas | As above | Provide protection for natural habitat and the species that depend on it in a specific area |

| Yukon First Nation Final Agreement (Note: this is not legislation) | Special Management Areas | As above | Protected areas established within a Traditional Area of a Yukon First Nation under a final agreement |

| NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (NT) | |||

| Territorial Parks Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c. T-4 | Cultural Conservation Areas | Department of Industry, Tourism and Investment | Protect culturally significant sites or landscapes |

| As above | Heritage Parks | As above | Preserve and protect significant cultural / historical natural areas, physical features, or built environments |

| As above | Natural Environment Parks | As above | To preserve and protect unique, representative, or aesthetically significant natural areas |

| As above | Recreation Parks | As above | To encourage an appreciation for the natural environment or to provide for recreational activities |

| As above | Wayside Parks | As above | To provide for the enjoyment or convenience of the traveling public |

| As above | Wilderness Conservation Areas | As above | To protect core representative areas that contribute to regional biodiversity, such as landforms, watersheds or wildlife habitats |

| NUNAVUT (NU) | |||

| Territorial Parks Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c. T-4… | See NWT details above | Department of Environment | See NT details above (still in review phase following consolidation of Act and its regulations from NWT) |

| Wildlife Act (Nunavut) | Special Management Areas | As above | To benefit one or more prescribed classes of wildlife or habitat; to preserve the ecological integrity of the area; to preserve biodiversity; or to provide for the application of special wildlife management rules for the area |

| As above | Critical Habitat | As above | Where necessary or advisable to protect a listed species, other than a species of special concern |

| As above | Wildlife Sanctuary | As above | For species management (these areas are continued from previous legislation, and no new ones are to be created) |

- Date modified: