Atlantic herring Division 4S (Herring Fishing Area 15)

Foreword

(Clupea harengus)

The purpose of this Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) is to identify the main objectives and requirements of the herring fishery on the Quebec North Shore in NAFO Division 4S (Herring Fishing Area 15) and the management measures that will be used to achieve these objectives. The IFMP is an evergreen working document produced by DFO, in collaboration with industry, and will be updated periodically. This document also provides background information and information related to management of this fishery to staff of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), co-management boards established by law under the regulations on territorial claims (if applicable) and other stakeholders. This IFMP provides a common interpretation of the fundamental “rules” that govern sustainable management of fisheries resources.

This IFMP is not a legally binding instrument which can form the basis of a legal challenge. The IFMP can be modified at any time and does not fetter the Minister’s discretionary powers set out in the Fisheries Act. The Minister can, for reasons of conservation or for any other valid reasons, modify any provision of the IFMP in accordance with the powers granted pursuant to the Fisheries Act.

Where DFO is responsible for the implementing obligation under land claim agreements or from Supreme Court judgments in relation to aboriginal rights, the IFMP will be implemented in a manner consistent with these obligations. In the event that an IFMP is inconsistent with obligations under land claim agreements, the provisions of the land claim agreements will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.

Maryse Lemire

Regional Director, Fisheries Management

DFO, Quebec Region

Table of Contents

1. Overview of the fishery

- 1.1 History

- 1.2 Type of fishery

- 1.3 Participants

- 1.4 Location of the fishery

- 1.5 Fishery characteristics

- 1.6 Governance

- 1.7 Approval process

5. Objectives

11. Glossary

12. Bibliography

13. Acronyms

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Changes in the number of herring fishing licences in Division 4S between 2010 and 2017, by gear type

- Appendix 2: Departmental contacts

- Appendix 3: Safety of fishing vessels at sea

Liste of figures

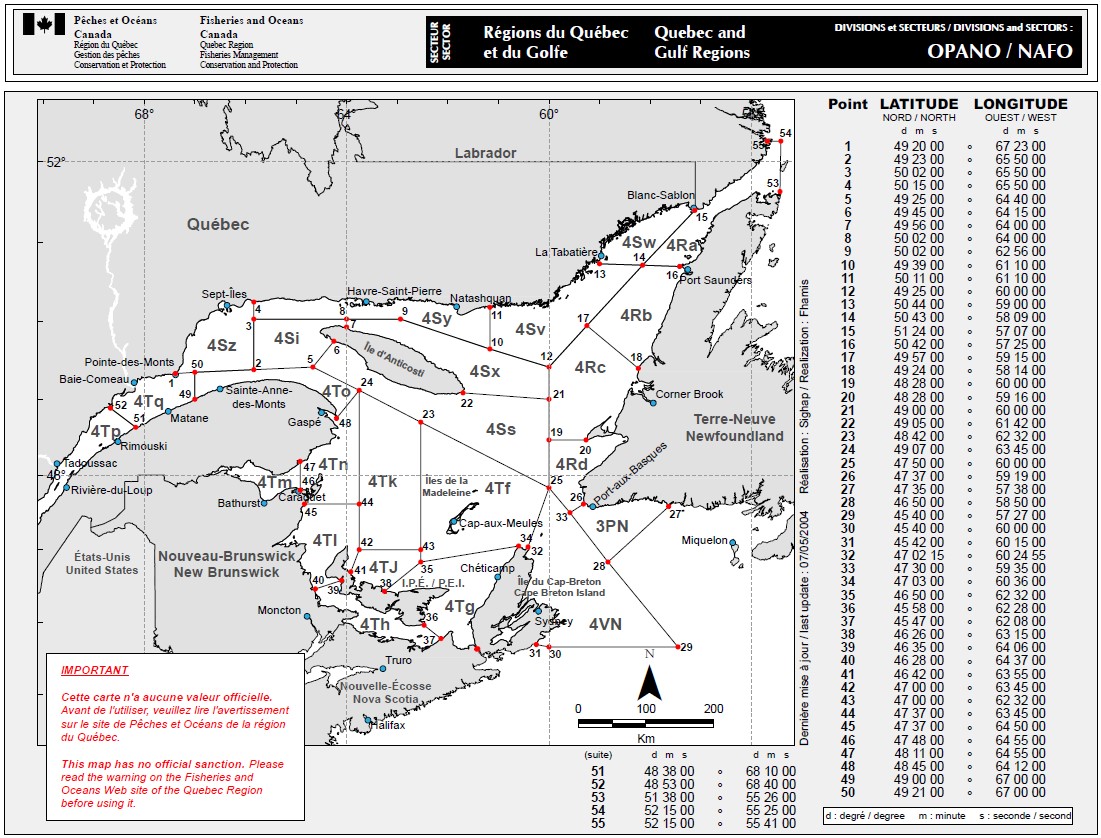

- Figure 1: NAFO divisions and areas in the Quebec and Gulf regions

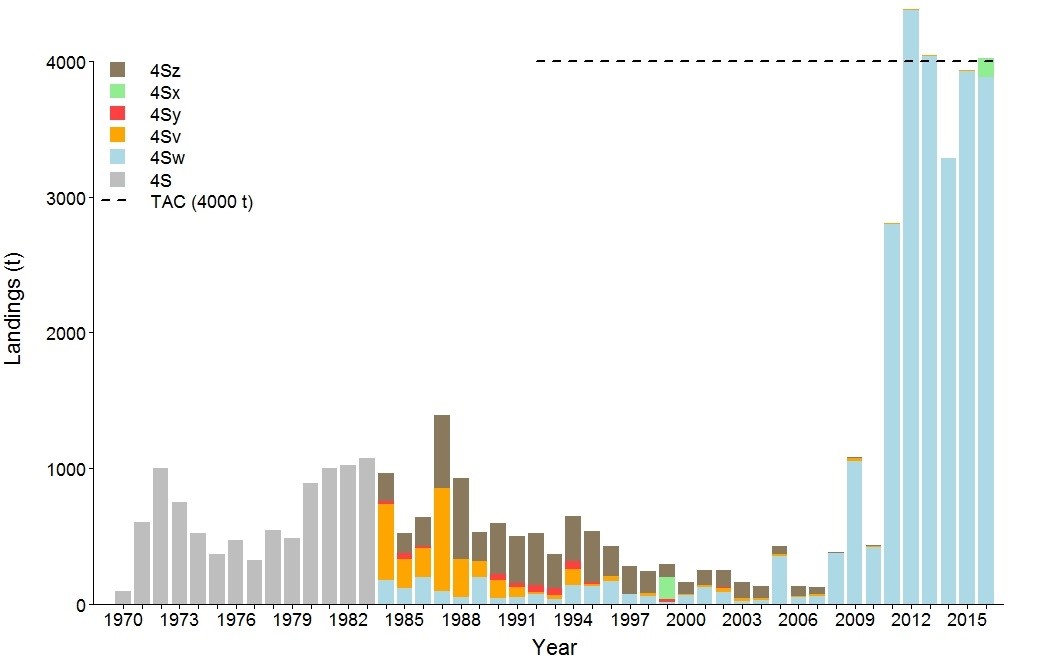

- Figure 2: Herring cumulative commercial landings (tonnes) for the unit areas of Quebec’s North Shore (NAFO Division 4S) from 1970 to 2016

- Figure 3: Biomass index (with standard error) of the spring-spawning stock (in green) and fall-spawning stock (in red) of herring in 4Sw, located in the eastern part of the Quebec LNS, as estimated by the acoustic surveys

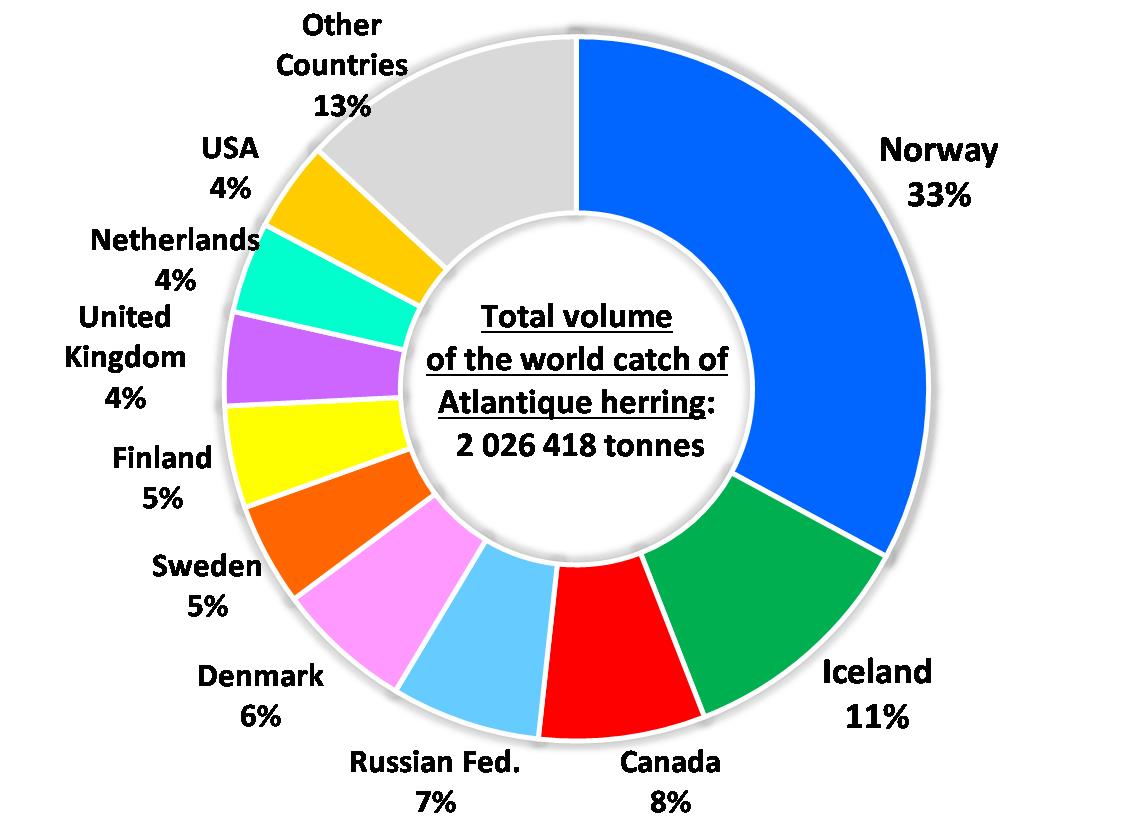

- Figure 4: Breakdown of the world Atlantic herring catch by country, 2000 to 2016 average

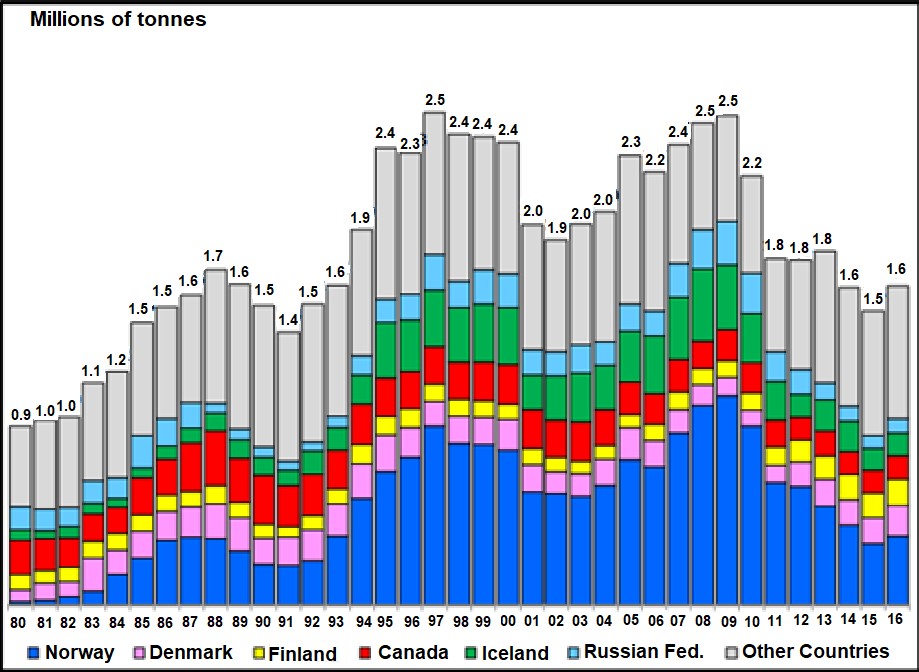

- Figure 5: Breakdown of the world Atlantic herring catch by country, 1980 to 2016

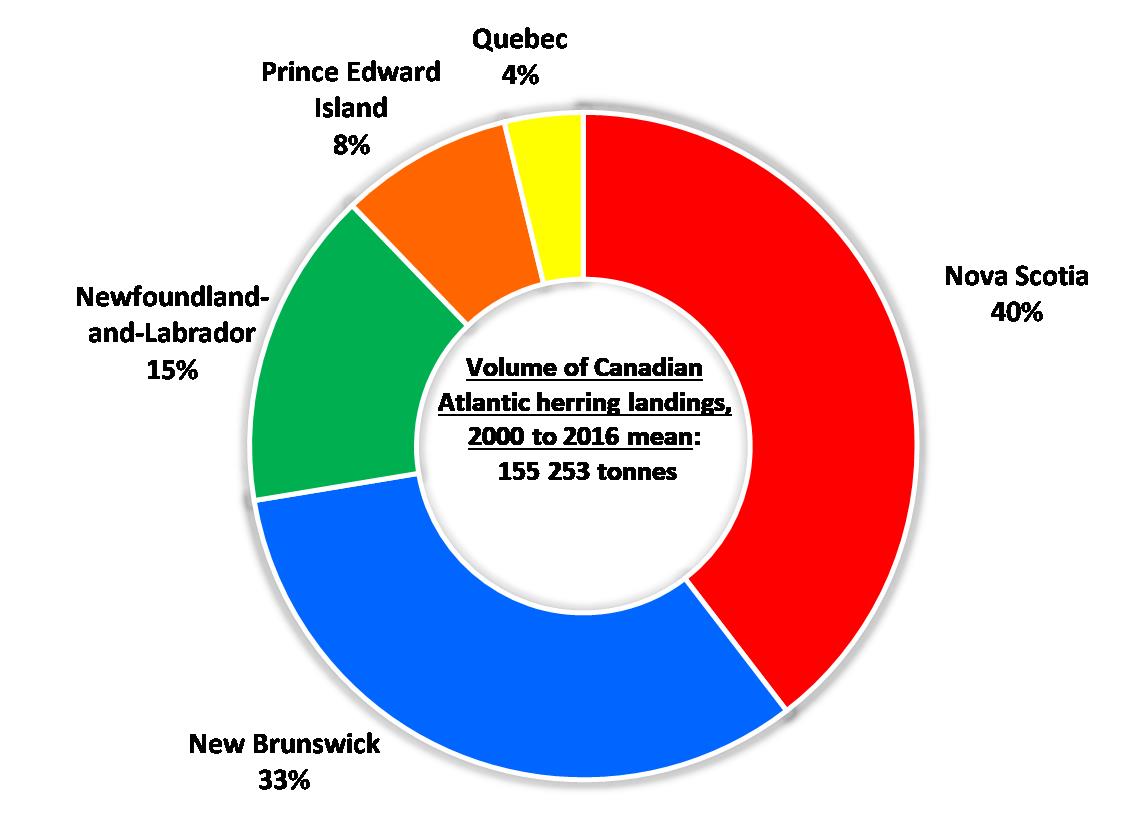

- Figure 6: Breakdown of Canadian Atlantic herring landings by province, 2000 to 2016 average

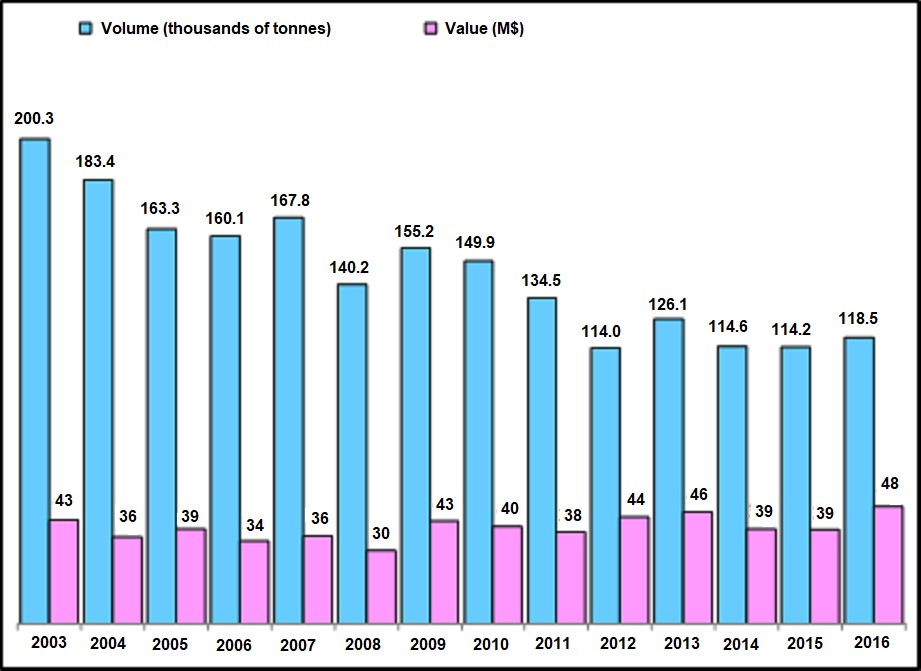

- Figure 7: Changes in volume and value of Canadian Atlantic herring landings, 2000 to 2016

- Figure 8: Changes in Quebec’s Atlantic herring landings by maritime area, 2003 to 2017

- Figure 9: Atlantic herring landed prices, average by maritime area, Quebec and Canada, 2000 to 2017

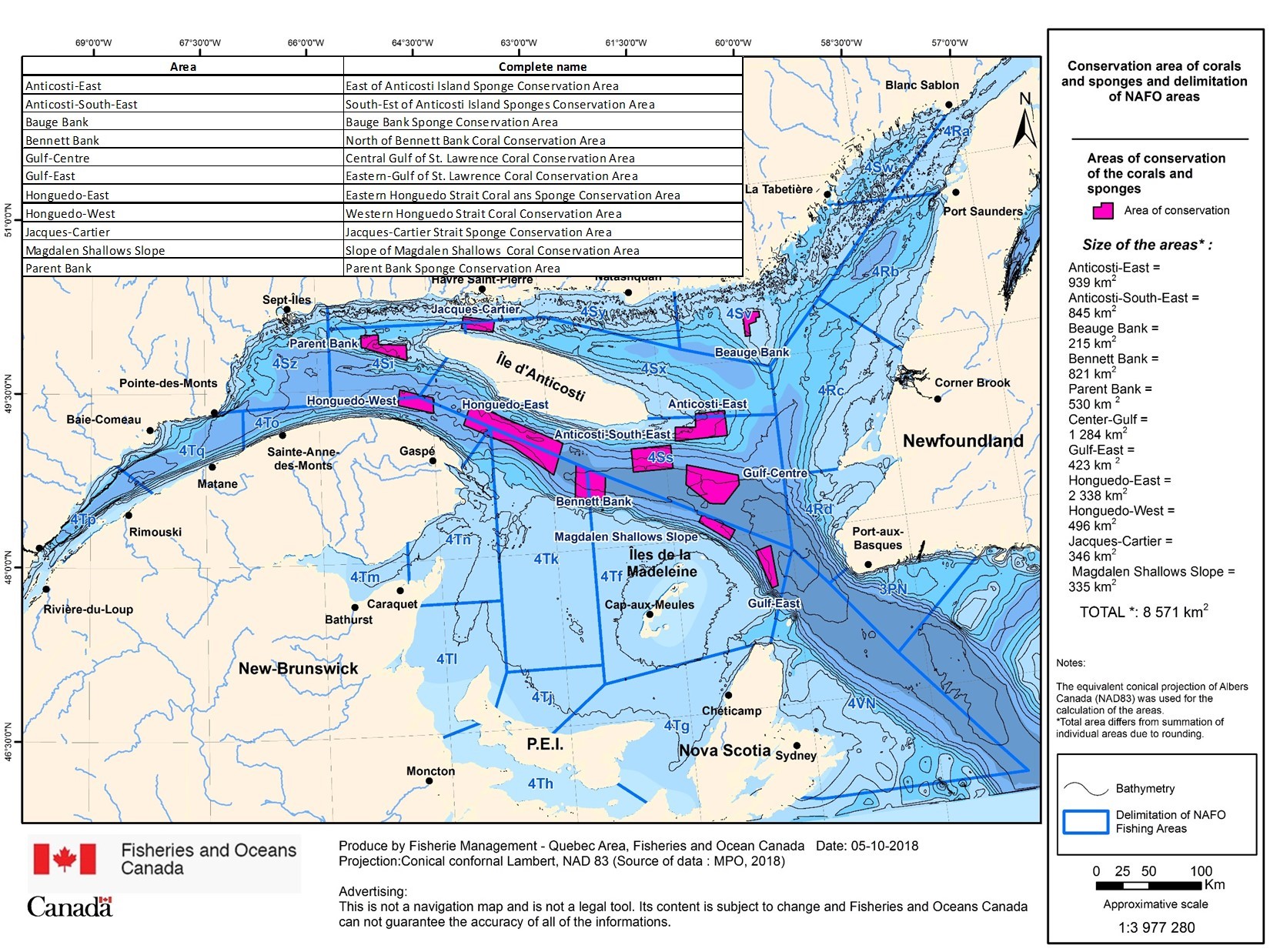

- Figure 10: Coral and Sponge Conservation Areas and NAFO Fishing Area Boundaries

1. Overview of the fishery

1.1 History

Development of the herring fishery

Atlantic herring has been commercially harvested since the late 1800s. Herring fishing and processing are highly diversified throughout the Atlantic regions. This diversity is explained by the multiple methods for preserving and using this resource. Over the years, herring has been preserved in a variety of ways—salted, smoked, pickled, canned and frozen—used as bait for other fisheries and as fertilizer, and reduced to meal and oil. More recently, herring has been harvested mainly for its eggs (roe) and sperm (milt).

The herring industry in the Maritimes and Quebec was developed in three phases. The first phase, pre-1960s, saw the development of the traditional processing industry. It was characterized by the creation of the Bay of Fundy canneries, the production of sardines from the Gulf of St. Lawrence gillnet fishery, and the production of barrels of pickled herring, sourced from the area west of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. During this period, landings fluctuated significantly from one year to the next.

The second phase stretched from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s. The onset of this phase coincided with the collapse of European herring stocks. At the same time, Canadian herring catches increased as large seiners focused their fishing effort on this species. From the early 1970s, higher European demand, combined with diminished stocks, lead to a sharp rise in herring prices, prompting increased interest by fishers in the species. In those years, several plants began processing herring along the North Shore (La Tabatière and Baie-Trinité). Harvesting and landings of Canadian herring stocks increased (Tremblay and Powles 1982).

In the late 1970s, European demand began to decline. At the same time, it became clear that the main Canadian stocks had been overharvested, resulting in a decline in interest in this resource.

In 1980, the reduction of the TAC for seiners contributed to the recovery and growth of herring stocks. The recovery of stocks, combined with poor groundfish markets, rekindled interest in the herring fishery. This change paved the way for the third phase, during which the Eastern European market opened up to processed and frozen Canadian herring. During this period, production of frozen herring roe also rose sharply to supply the new Japanese market.

In the 1980s, significant annual variation in landings was observed as a result of the fluctuating demand for herring, the main market being as bait for crab, lobster and groundfish fisheries.

Evolution of the fishery (1990 to 2005)

The successive moratoria on the cod fishery in the early 1990s and on the crab fishery in the early 2000s had a significant impact on the fishing industry and on the local communities of the North Shore, which, because of their geographic isolation, rely heavily on marine resources.

In addition, between 1995 and 2006, New Brunswick’s large seiners applied for several exploratory licences to assess the potential of the herring fishery in Division 4S (Figure 1), an area in which directed herring fishing effort was historically low. Except from 2004 to 2006, the applications were always turned down by the industry, the province of Quebec and DFO in order to protect the North Shore’s traditional inshore fleet.

It is against this backdrop that the Area 15 Herring Advisory Committee was set up. It met for the first time in September 2004, and that meeting led to the drafting of a short-term action plan that included objectives related to the economic outlook for North Shore herring.

North Shore stakeholders’ development plan for pelagic species (2005 to 2018)

Pressure from fishers from other provinces for access to the pelagic resources in area 4S prompted the Quebec industry to structure and develop itself on the North Shore. During a period of challenging economic times for the Lower North Shore (LNS) fishing industry, the first regional development plan for the 4S herring fishery was developed in 2005 by a working committee of fishers’ associations, Aboriginal groups and processors. The objective of the plan was to increase fishers’ stability and versatility and to facilitate the restructuring of North Shore fleets. Meanwhile, between 2006 and 2010, DFO and the industry jointly developed the first Area 15 integrated fisheries management plan (IFMP) to ensure the sustainable development of the North Shore herring fishery.

In 2007, the herring fishery’s regional development plan was included in a five-year plan for the sustainable development of pelagic species in Quebec’s North Shore. The main thrusts of the plan were as follows:

- improving knowledge of herring stock jointly with DFO;

- enhancing the capability of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal fishers by activating unused licences;

- facilitating joint work between the various fishing industry stakeholders;

- developing marketing and product diversification strategies.

The plan was updated in 2013, and the objective of the second five-year plan was to ensure the sustainability of the pelagic species industry. Industry stabilization and fisheries diversification remain the plan’s key objectives.

Fishery management

Since the early 1970s, the herring fishery has been managed through a total allowable catch (TAC) and the allocation of quotas. A preventive quota of 1000 t was in place until 1991. That year, an additional quota of 3,000 t was allocated for over-the-side sales, for a TAC of 4,000 t. The prohibition of over-the-side sales in 1993 ensured that the entire TAC in Division 4S would be reserved for vessels less than 50 ft in the inshore fishery. The preventive TAC of 4,000 t remains in effect in 2018. A formal TAC cannot be established due to a lack of scientific information.

Fishing methods

Prior to 1981, anchored gillnets were the only gear used for herring. From 1984 to 2007, 85% of the catch reported in Division 4S had been fished with gillnets. However, as of 2005, fishing methods became more diversified. Herring caught with traps peaked at 1,576 t in 2012. Between 2008 and 2010, trap catches averaged 73% of the annual catch in the eastern area of the Division.

Though historically marginal, purse seine catches increased substantially starting in 2011. This highly effective method, which is used exclusively in the Blanc-Sablon area, resulted in a significant increase in landings, and in 2012, the TAC was met for the first time. Since 2011, 80% of herring landings are caught with purse seines, 18% with traps and less than 2% with gillnets (DFO 2017).

First Nations

The development of DFO’s Aboriginal Fisheries Program gained momentum with the 1990 Sparrow decision, which provides a thorough analysis of subsection 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, which recognizes and affirms the ancestral and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, including the right to fish. An initial Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) was implemented in 1992 with the objective of governing the Aboriginal food, social and ceremonial fishery and providing Aboriginal peoples with the opportunity to participate in fisheries management.

Under this program, DFO concluded agreements with First Nations to establish a regulatory framework for the management of their fisheries. These agreements also aim to integrate Aboriginal people into commercial fishing, provide economic benefits and determine subsistence fishery allocations.

In 1994, improvements were made to the strategy following the implementation of the allocation transfer program, which facilitated First Nations’ entry into the commercial fishery without increasing pressure on stocks. Commercial fishers could voluntarily sell their allocations to DFO, which would re-allocate them to First Nations groups through communal licences.

In principle, DFO intended to buy back licence holdings and issue them to First Nations to give them access to various species in order to support their fishing businesses. Herring gillnet licences were reissued to North Shore Innu communities, as were food, social and ceremonial (FSC) fishing allocations. Still today, First Nations members seldom fish herring with nets, traps or beach seines.

1.2 Type of fishery

There is both a commercial and bait fishery for herring. Herring is not currently fished for food, social and ceremonial (FSC) purposes. A certain quantity of herring nonetheless remains reserved for this type of fishery.

1.3 Participants

In 2017, there were 254 herring licence holders in Division 4S. However, only 14 licences (5.5%) were active, meaning that they reported at least one landing (Table 1). No Aboriginal communities participated in the herring fishery in 2017. Appendix 1 shows the changes in the number of herring fishing licences in Division 4S, between 2010 and 2017, for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, by fishing gear type.

| Aboriginal | Non-Aboriginal | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing gear | Active | Inactive | Active | Inactive | |

| Gillnet | 0 | 13 | 3 | 201 | 217 |

| Trap | 0 | 1 | 5 | 19 | 25 |

| Purse seine | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Purse seine (exploratory) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 0 | 14 | 14 | 226 | 254 |

1.4 Location of the fishery

Herring Fishing Area 15 corresponds to NAFO Division 4S, which stretches from Pointe-des-Monts to Blanc-Sablon, including the waters surrounding Anticosti Island (Figure 1). Despite the very large size of Division 4S, most historical landings are concentrated at either end of this area. Between 1984 and 2007, an average of 56% of catches were from the western area (4Sz). However, the fishing effort has shifted considerably since 2008, with more than 97% of the catch being fished in the eastern area, largely concentrated at the east end of 4Sw, between Vieux-Fort and Blanc-Sablon (DFO 2017). This shift can be partly explained by fact that herring fishers on the Upper and Middle North Shore (UMNS) withdrew from the herring fishery in favour of other, more lucrative fisheries, such as the snow crab, clam and groundfish fisheries. For their part, fishers on the Lower North Shore diversified their fishing activities by developing the pelagic fisheries sector, which includes herring. Harbour facilities on the Lower North Shore were upgraded, and the acquisition of pumps for unloading their catches fish resulted in a significant increase in landings of pelagic species.

1.5 Fishery characteristics

Under the Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985 (AFR 1985), herring fishing on the North Shore is authorized from January 1 to December 29. However, fishing activities are typically concentrated from spring to late summer in 4Sz (western sector), and from spring to early autumn in 4Sv and 4Sw (eastern sector).

The AFR 1985 prohibits the catching of herring less than 26.5 cm in length. However, this minimum size does not apply to herring caught with gillnets.

1.6 Governance

Fishing activities are first and foremost subject to the Fisheries Act and its regulations, specifically, the AFR 1985 and the Fishery (General) Regulations. The Species at Risk Act, which was passed in 2002, sets out rules for endangered and threatened species.

The management of herring fishing in Herring Fishing Area 15 is the responsibility of the Resource and Aquaculture Management and Aboriginal Affairs (RAMAA) Direction in Québec. The herring management plan for Herring Fishing Area 15, including the TAC, is approved by the Regional Director, Fisheries Management (RDFM). Decision making by the RDFM is supported by various recommendations, including those of industry. Meetings with industry, held via an advisory committee or workshop, are coordinated by the North Shore Area Director. The recommendations arising from these meetings are taken into account in discussions among several stakeholders, including the other Area Directors, Science Branch, and the senior advisor for the species. The final recommendations are presented to the RDFM.

1.7 Approval process

The development of the IFMP is coordinated by the RAMAA in Quebec City. The document drafting and consultation process involves the Resource Management and Aquaculture Division in Quebec City and on the North Shore, Strategic Services and Regional Science Branch (Quebec Region), fishers’ organizations, First Nations, the processing industry and the province of Quebec. The final draft of the IFMP is approved by the RDFM, Quebec Region. The approved IFMP is sent to the fishery stakeholders and publicly released. The Regional Director approves the posting of the IFMP on the DFO website.

2. Stock assessment, scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge

2.1 Biological synopsis

Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) is a pelagic fish found in cold Atlantic waters. Its range in Canada extends from the coasts of Nova Scotia to the coasts of Labrador. It spawns near the coast and overwinters in deeper waters. It travels in tight schools between its spawning, feeding and over-wintering areas, returning to the same sites year after year. This homing phenomenon is attributed to a learning behaviour with the recruitment of young year-classes in a population.

At spawning, eggs attach themselves to the sea floor, forming a carpet a few centimetres thick. Egg incubation time and larval growth are linked to ambient environmental characteristics such as water temperature. Most herring reach sexual maturity at 4 years of age, at a total length of about 25 cm. The herring populations of the Quebec North Shore are characterized by two groups or spawning stocks. Spring herring generally spawn in April and May, and fall herring spawn in August and September. According to the observations of some fishermen, exchanges could take place between the herring stock in sector 4Sw and that in division 4R.

2.2 Ecosystem interactions

Herring is a very important link in the food chain of the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. According to models of the marine ecosystem of the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence (NAFO divisions 4RS), predation is the main cause of herring mortality. Over the years, this forage species has been found, to varying degrees, in the diet of many species, including redfish (Sebaste spp.), large cod (Gadus morhua), harp seals (Phoca groenlandica), cetaceans and grey seals (Halichoerus grypus).

Herring feeds mainly on small (less than 5 mm, mostly copepods) and large zooplankton (more than 5 mm, euphausids and amphipods). Recent research has shown that herring recruitment from the west coast of Newfoundland and the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence (NAFO divisions 4RT) is influenced by zooplankton dynamics, and to a lesser extent , by the environmental physical conditions (Brosset et al., 2018). These results suggest that changes in zooplankton abundance, species composition and phenology may affect the productivity of herring stocks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

2.3 Aboriginal traditional and ecological knowledge

Management decisions take into account Aboriginal traditional knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge provided in the form of observations and comments by Aboriginal groups.

Several industry representatives suggested that the resource would respond to variations in environmental conditions. Over the past decade, some fishers have reportedly observed the presence of herring outside traditional fishing areas, particularly in deeper waters than in the past.

2.4 Stock assessment

The spring and fall herring spawning components in NAFO Division 4S are considered to be discrete stocks and, as such, are evaluated separately. The assessment of herring stock status is based primarily on an analysis of biological indicators (age structure, length and weight at age, and condition) calculated using commercial fishery samples. Annual samples are collected throughout the fishing season, in the main landing ports of Quebec’s North Shore.

Annual catch-at-age composition indicates that both spawning components of the Quebec North Shore are characterized by the periodic occurrence of dominant year-classes. Among both spring and fall spawners, the most recent year-class is 2005, and to a lesser extent, 2008. However, the 2005 year-class (11-year-old fish) continued to dominate commercial catches in 2016. This year-class alone represented 28% of spring-spawner catches and 40% of fall-spawner catches.

Among spring spawners, a new year-class, 2013, seems to have entered the fishery in 2016. It will take several years before its size can be assessed.

To obtain fishery-independent abundance indices for both herring spawning stocks in Quebec’s North Shore, the first acoustic survey covering the entire 4S coastal zone was conducted in autumn 2016. The most significant acoustic signals were measured near Havre-Saint-Pierre. For the entire 4S coastal zone, the total biomass index was estimated at 830 t for spring spawners and 21,477 t for fall spawners. The survey is scheduled to be conducted every two years.

Four acoustic surveys were also conducted between 2009 and 2013 at the east end of the area, around Blanc-Sablon. These acoustic surveys revealed that the biomass index of spring spawners in 4Sw plummeted between 2009 and 2016, from 1,041 t to 41 t (Figure 3). In 2009, spring herring accounted for 16% of the biomass of both spawning stocks, compared with just under 3% in 2016. The biomass index of fall spawners in 4Sw also dropped sharply between 2010 and 2016, from 27,087 t to 1,518 t (Figure 3).

The is available in the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) section of our website.

2.5 Stock scenarios

The results of the acoustic surveys conducted by DFO in 4Sw from 2009 to 2016 suggest an almost complete disappearance of spring-spawning herring as well as a sharp decrease in the abundance of fall-spawning herring. Both stocks consist mainly of fish ages 10 and older.

Catches between 2009 and 2016 were supported primarily by the dominant 2005 year-class of fall spawners. Due to natural mortality and fishing mortality, the abundance of old fish that have supported the fishery in recent years will continue to decline.

Given the lack of significant recruitment, the older age of fish in catches, and the decrease in the 4Sw biomass index, the current 4Sw catch level may lead to a local depletion of the resource. During the last herring stock assessment in Division 4S in 2016, DFO scientists recommended identifying measures to better distribute fishing effort along the north shore. Moreover, the TAC of 4,000 t should not be increased given the total biomass index in 4S. If measures are not implemented to reduce fishing effort in 4Sw, the TAC should be reduced. Management measures should also be implemented to protect the spring spawning period.

2.6 Precautionary approach

The precautionary approach in fisheries management involves exercising caution when conclusive scientific evidence is unavailable, and not using the absence of relevant scientific data as a reason for failing to take action or delaying action to prevent serious harm to fish stocks or their ecosystems. This approach is widely accepted as an essential part of sustainable fisheries management. Applying the precautionary approach to fisheries management decisions entails establishing a harvest strategy that:

- identifies three stock status zones (healthy, cautious and critical) according to upper stock and limit reference points;

- sets the removal rate at which fish can be harvested within each stock status zone;

- adjusts the removal rate according to fish stock status variations (i.e. spawning stock biomass or another index/metric relevant to population productivity), based on decision rules.

Within the framework of the precautionary approach, biomass reference points have been established for both herring spawning stocks. For now, no analytical assessment has been conducted for the two herring spawning stocks on Quebec’s North Shore. Once the new series of acoustic surveys for the entire 4S division is long enough, it will be possible to analytically assess both herring spawning groups, as well as establish limit reference points to define a strategic framework based on the precautionary approach for the fishery.

2.7 Research

A primary goal of the DFO Science branch is to provide high quality knowledge, products and scientific advice on Canadian aquatic ecosystems and living resources, with the aim of safe, healthy, productive waters and aquatic ecosystems. DFO conducts research activities both independently and in collaboration with other organizations.

The work deemed a priority by the last peer review aims to:

- continue and refine the acoustic survey;

- improve commercial and acoustic sampling (more sampling, better dispersion);

- improve the agreement rate for age estimation between otolith readers, especially for ages ≥ 9;

- determine the causes of the spring herring’s near disappearance;

- examine potential exchange between 4R and 4S herring, via otolith assessment for example;

- investigate the possibility of developing a gillnet survey in 4S, as is the case for 4T.

3. Economic, social and cultural importance of the fishery

Atlantic herring is one of the most abundant marine species in the world, living in the open ocean and gathering in large schools that are constantly on the move. It is found on both sides of the Atlantic. Specifically, it is found in the Gulf of Maine, the Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Labrador Sea, the Davis Strait, the Beaufort Sea, the Denmark Strait, the Norwegian Sea, the North Sea, the Baltic Sea the English Channel, the Celtic Sea and the Bay of Biscay.

3.1 World landings of Atlantic herring

The Atlantic herring fishery is conducted by about 20 countries, most of which are European. Between 2000 and 2016, Norway dominated world landings, accounting on average for one-third of the world total, or about 667,000 t. Iceland ranked second with 11% of world landings, or about 227,000 t. Canada was third with a market share of 8%, or about 155,000 t. These countries were followed by the Russian Federation, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States.

Source: FAO, United Nations.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

Description

Figure 4: The Atlantic herring fishery is conducted by about 20 countries, most of which are European. Between 2000 and 2016, Norway dominated world landings, accounting on average for one-third of the world total, or about 667,000 t. Iceland ranked second with 11% of world landings, or about 227,000 t. Canada was third with a market share of 8%, or about 155,000 t. These countries were followed by the Russian Federation, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States (FAO, compilation of Strategic Service (DFO Quebec)).

The Atlantic herring fishery is conducted by about 20 countries, most of which are European. Between 2000 and 2016, Norway dominated world landings, accounting on average for one-third of the world total, or about 667,000 t. Iceland ranked second with 11% of world landings, or about 227,000 t. Canada was third with a market share of 8%, or about 155,000 t. These countries were followed by the Russian Federation, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States.

In terms of commercial value, the world’s largest Atlantic herring stock by far is the Norwegian spring-spawning stock in the Northeast Atlantic. This stock is fished by many countries and is subject to a management plan signed between the European Union, the Faroe Islands, the Russian Federation, Norway and Iceland. Fluctuations in the total world Atlantic herring catch are very strongly correlated with Norway’s total catch of this stock, as shown in figure 5.

Source: FAO, United Nations.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

Description

Figure 5: Between 2009 and 2016, Atlantic herring catches dropped by one-third, from 2.5 to 1.6 t. Catches of the three main producing countries (Norway, Iceland and the Russian Federation) in those years declined by 67%, 65% and 67%, respectively. The low recruitment rate of the resource, possibly related to environmental conditions, was cited as an explanation for the significant decline in biomass, although this explanation was not formally backed by scientific studies (FAO, compilation of Strategic Services (DFO Quebec)).

In the early 2000s, the low recruitment of the North Sea stock (fall-spawning herring) coupled with the reduction in Scandinavian-Atlantic quotas by one-third caused a sharp decline in catches in several Northern European countries, putting upward pressure on herring prices.

Between 2009 and 2016, Atlantic herring catches dropped by one-third, from 2.5 to 1.6 t. Catches of the three main producing countries (Norway, Iceland and the Russian Federation) in those years declined by 67%, 65% and 67%, respectively. The low recruitment rate of the resource, possibly related to environmental conditions, was cited as an explanation for the significant decline in biomass, although this explanation was not formally backed by scientific studies.

The world supply of herring is therefore highly dependent on the Norwegian catch and fluctuates significantly over the years, depending on changes in the quotas of the Norwegian stock. As a result, the world price of Atlantic herring, which is highly correlated with the world supply, also fluctuates considerably.

3.2 Canadian landings of Atlantic herring

In Canada, the Atlantic herring commercial fishery is conducted mainly on the southwest coast of Nova Scotia and in the Bay of Fundy, in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, and on the east and west coasts of Newfoundland-and-Labrador. In recent years, efforts have also been made to develop the herring fishery on Quebec’s North Shore (NAFO Division 4S).

Between 2000 and 2016, Canadian landings of Atlantic herring averaged 155,300 t. In terms of volume, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick landed nearly three-quarters (73%) of the total Atlantic herring catch in Canada. Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and Quebec followed, with a relative share of 15%, 8% and 4%, respectively. In terms of value, the provinces’ relative share of Atlantic herring catches is very similar to their share of landed volume.

Source: DFO, Quebec Region, Newfoundland and Labrador Region, Gulf Region and Maritimes Region.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

Description

Figure 6: Between 2000 and 2016, Canadian landings of Atlantic herring averaged 155,300 t. In terms of volume, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick landed nearly three-quarters (73%) of the total Atlantic herring catch in Canada. Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and Quebec followed, with a relative share of 15%, 8% and 4%, respectively. In terms of value, the provinces’ relative share of Atlantic herring catches is very similar to their share of landed volume (DFO, data coming directly from the Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Gulf and Maritimes Regions, compilation of Strategic Services (DFO Quebec)).

The Atlantic herring fishery is important for the Maritimes and Quebec. In Canada, Atlantic herring catches alone account for 70% of the total pelagic catch and 19% of the total catch all species combined. In terms of value, this fishery accounts for 42% of the total catch value of pelagic species and for 2% of the total catch value of all species combined.

Between 2003 and 2016, Canadian landings of Atlantic herring gradually decreased from 200,300 t to 118,500 t, a 41% decline. Specifically, landings declined by 46% in Nova Scotia, 53% in New Brunswick and 73% in Prince Edward Island, due to the decrease in the quota in Division 4T. In contrast, they increased by 3% in Quebec and 34% in Newfoundland, reflecting the observed increase in herring landings from Divisions 4R and 4S.

Source: DFO, Quebec Region, Newfoundland and Labrador Region, Gulf Region and Maritimes Region.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

3.3 Quebec landings of Atlantic herring

The Atlantic herring fishery in maritime Quebec is important for several reasons. Herring is fished both for human consumption and for use as bait in lobster, crab and whelk traps. Between 2003 and 2017, in Quebec, Atlantic herring catches alone represented on average 72% of the total catch of pelagic species and 10% of the total catch of all species combined.

In 2017, herring landings in Quebec totalled 5,600 t, for a value of $1.8 million. Between 2003 and 2017, Atlantic herring landings in Quebec’s maritime areas were as follows: 57% in the Gaspé Peninsula, 27% on the North Shore and 16% in the Magdalen Islands.

Herring catches for personal use as bait are not accurately reflected in landing statistics, which contributes to a slight underestimation of reported annual landings of herring. As well, in rare years, North Shore herring fishers have landed their catches in Newfoundland. However, given the small number of these fishers, statistics on these landings cannot be disclosed due to confidentiality concerns.

Source: DFO, Quebec Region.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

Description

Figure 8: In 2017, herring landings in Quebec totalled 5,600 t, for a value of $1.8 million. Between 2003 and 2017, Atlantic herring landings in Quebec’s maritime areas were as follows: 57% in the Gaspé Peninsula, 27% on the North Shore and 16% in the Magdalen Islands (DFO, data coming directly from the Quebec Region, compilation of Strategic Services (DFO Quebec)).

Prior to 2005, the Gaspé Peninsula and Magdalen Islands accounted for the largest share of herring landings in Quebec, whereas catches on the North Shore were minimal. In 2003, the Magdalen Islands and the North Shore accounted for 39% and 3%, respectively, of total herring landings in Quebec. In 2017, the North Shore accounted for 56% of total herring landings, ahead of the Gaspé Peninsula (43%), whereas herring landings in the Magdalen Islands accounted for only 1% of the total.

On the North Shore, better access to herring markets through plants in Newfoundland has greatly contributed to the development of this fishery since 2011. Between 1979 and 2010, annual reported herring landings in Division 4S averaged 590 t, ranging from a maximum of 2,885 t in 1983 to a minimum of 120 t in 2007. Between 2010 and 2011, landings increased sharply, from 429 t to 2,100 t, an increase of 397%. Between 2012 and 2017, annual herring landings on the North Shore averaged 3,700 t, very close to the annual preventive TAC of 4,000 t, which was exceeded in 2013. In contrast, in the Magdalen Islands, herring have disappeared from the waters around the archipelago, which explains the drop in herring landings.

Since 2011, the landed value of Atlantic herring in Quebec has exceeded $2 million, reaching a record high of $3.2 million in 2012. Between 2003 and 2017, the catch value of Atlantic herring in Quebec represented on average 58% of the value of total catches of pelagic species, but only 1% of the total value of all species combined. The herring fishery is not considered lucrative for fishers because of the low average landed price they receive. Despite its low value, the fishery is nevertheless vitally important as one of the main sources of bait fish used in other fisheries (snow crab, lobster, whelk, tuna, etc.).

Source: Seafood Price Current – Urner Barry’s COMTELL; DFO, Quebec Region.

Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region.

Description

Figure 9: Since 2000, landed herring prices have trended upwards. Between 2000 and 2017, the annual landed price of herring in Quebec and Canada increased by 104% and 168%, respectively. During the same period, the landed price increased by 185% in the Gaspé Peninsula, 75% in the Magdalen Islands and 55% on the North Shore (Seafood Price Current – Urner Barry’s COMTELL; DFO, Quebec Region, compilation of Strategic Services (DFO Quebec)).

The landed price of Atlantic herring in Quebec and Canada is based on herring prices in Norway. As the world’s largest producer, Norway is the reference market for world prices of Atlantic herring. Between 2010 and 2017, the average annual landed price of herring in Quebec and Canada was $0.16/lb. In the Gaspé Peninsula, it was $0.22/lb, but on the North Shore it was $0.08/lb.

Nearly all herring bought by the three North Shore facilities was redirected, unprocessed, to the Barry Group facility in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, for processing. This explains the low average landed price paid to North Shore herring fishers.

Since 2000, landed herring prices have trended upwards. Between 2000 and 2017, the annual landed price of herring in Quebec and Canada increased by 104% and 168%, respectively. During the same period, the landed price increased by 185% in the Gaspé Peninsula, 75% in the Magdalen Islands and 55% on the North Shore.

3.4 Quebec production of Atlantic herring

In Quebec, herring is fished for human consumption and for use as bait. These two fisheries account for 63% and 37% of total sales, respectively. On the North Shore, annual bait herring production is stored by facilities to supply mainly crab and lobster fishing vessels throughout the following year’s fishing season. In the other maritime areas (Gaspé peninsula and Magdalen Islands), there is also a small local market for whole fresh herring. Herring roe, the most lucrative product, is exported entirely and exclusively to the Japanese market. Smoked herring ("bloater" herring) is destined for the Caribbean market, whose main destinations are the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica and the Netherlands Antilles. Smoked herring is also exported to the United States, which is very popular with American consumers of Caribbean origin.

Year after year, the sales value of herring production by facilities is nearly four times that of herring landings. This difference corresponds to the value added resulting from the processing of herring before it is sold on the local market or exported abroad.

3.5 Economic spin-offs of the area 15 herring fishery

In terms of jobs, the herring fishing industry in Quebec helps create jobs in the three maritime areas where the job market is often precarious and seasonal.

The change in the regional profile of herring landings had repercussions on the number of jobs in the primary sector of the herring fishery in the maritime areas. Between 2002 and 2017, the total number of fishers (captains and crew) active in the Quebec herring fishery decreased from 598 to 337, a 44% drop. On the North Shore, the number of fishers (captains and crew) continued to decline, from 111 in 2002 to 31 in 2017, a 72% drop, despite the significant increase in herring landings noted since 2011.

In Quebec’s secondary herring processing sector, the total number of jobs is estimated at 431, divided between the three maritime areas as follows: 356 in Gaspé–Lower St. Lawrence, 70 on the North Shore, and 5 in the Magdalen Islands. These workers represented about 10% of the total number of jobs in Quebec’s marine product processing industry.

3.6 Economic issues of the herring fishery

The North Shore herring fishing industry is affected by several economic issues.

- The primary issue is the absence of a herring processing facility on the Lower North Shore. The Barry’s Group facilities in Blanc-Sablon and I & S Seafood (Irving Roberts) in Rivière-Saint-Paul buy Lower North Shore herring landings and ship them all to Newfoundland for processing.

- The Lower North Shore’s isolation and lack of road links with the rest of Quebec hinder development of a bait herring industry. In addition, the lack of freezer capacity precludes the storage of bait for other local fisheries. Several fisheries require bait (whelk, rock crab, snow crab, and lobster). Bait is typically imported and is not fresh when it arrives on the North Shore.

4. Management issues

This section gives an overview of the management issues specific to the herring fishery in Division 4S. The issues addressed here take into account the various policies and fisheries frameworks in place to ensure the conservation and sustainability of the commercial fishery, including the Sustainable Fisheries Framework, which encompasses several frameworks and policies for conservation and sustainable resource use. This framework and its various related policies are available in the Fisheries Policies and Frameworks section of our website.

The key issues were identified on the basis of advisory committee proceedings, scientific advice, and the five-year plan for the sustainable development of the pelagic species of Quebec’s North Shore (2013 to 2018), and in consultation with the industry. They are grouped into five themes:

- Fishery conservation and sustainability

- Habitat and ecosystem

- Fishery governance

- Economic prosperity

- Compliance

4.1 Fishery conservation and sustainability

Since 1992, the herring fishery in this fishing area has been managed by a preventive total allowable catch (TAC) of 4,000 t, without distinction for spawning groups, due to the lack of scientific information for the establishment of a formal TAC. In addition, potential spawning areas and spawning dynamics are not identified. This makes it difficult to protect the spawning biomass so as to promote herring recruitment. The lack of information on the various biological components of herring in Division 4S limits the implementation of adapted management measures, including a strategic framework for the herring fishery based on the precautionary approach.

4.2 Habitat and ecosystem

The loss or abandonment of fishing gear at sea can have major impacts on the ecosystem. These impacts may include ghost fishing, entanglement (of sea turtles, marine mammals and seabirds) and alteration of the benthic environment. The lack of information about these impacts makes it difficult to implement appropriate measures to reduce the impact of herring fishing on the ecosystem.

DFO relies on the Species at Risk Act (SARA), among other things, to ensure the protection of Canada’s biodiversity. Recovery strategies for species at risk aim to meet specific objectives relating to commercial fisheries. Further information on aquatic species at risk and their recovery strategies is available in the Aquatic Species at Risk section of our website.

In addition, certain species may be present in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence such as: Striped Bass (St. Lawrence Estuary population), North Atlantic Right Whale, Blue Whale (Atlantic population), Beluga Whale (St. Lawrence Estuary population) and Great White Shark. Please refer to section 7.4 for more information on the requirements of the SARA.

Conservation of cold-water corals and sponge reefs

The Government of Canada is committed to protecting 5% of Canada’s marine and coastal areas by 2017 and 10% by 2020. The 2020 target is both a domestic target (Canada’s Biodiversity Target 1) and an international target as reflected in the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Target 11 and the United Nations General Assembly’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development under Goal 14. The 2017 and 2020 targets are collectively referred to as Canada’s marine conservation targets. More information on the background and drivers for Canada’s marine conservation targets is available on our website.

The DFO is establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and “other effective area-based conservation measures” (OEABCM) in consultation with industry, non-governmental organizations, and other interested parties that help meet these targets. An overview of these tools, including a description of the role of fisheries management measures that qualify as OEABCM, is available on our website.

Specific measures for the conservation and protection of cold water corals and sponges that affect the herring fishery in Division 4S qualify as OEABCM and therefore contribute to Canada’s marine conservation targets. More information on these management measures and their conservation objectives is provided in section 7.5 (Management Measures) of this IFMP.

4.3 Fishery governance

Governance entails the implementation of a structure and management mechanism to ensure shared management by DFO and industry in the development of management measures that taken into account the economic realities of the sectors.

The Area 15 Herring Advisory Committee is the primary mechanism set up to ensure sound governance of this fishery. The participation of the fishing industry in the decision-making process is important to ensuring sound governance of the fishery. Exchanges and collaboration between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal fishers are required to promote sound governance. The established governance structure ensures the harmonious use of fishing grounds and minimizes use conflicts.

4.4 Economic prosperity of the fishery

The profitability of fishing enterprises is important to the economy of the North Shore regions, particularly the Lower North Shore, given its geographical remoteness and given the very important role marine resources play in its economy. The industry can take action to develop markets, promote fishery products and increase processing capacity so as to boost the economic prosperity of 4S herring fishers.

4.5 Compliance

The collection of data on catches, landings, fishing locations, impacts on ecosystems, and compliance is critical to managing the herring fishery in Division 4S. Fishery monitoring requirements must be identified in order to obtain timely, reliable and accessible data for effective fishery management.

5. Objectives

The objectives defined in this section are intended to address the management issues covered in the previous section; these have been developed with the industry.

5.1 Fishery conservation and sustainability

To ensure the sustainability of the fishery and the conservation of the resource, the collection of missing data is critical. Data related to the spring- and fall-spawning stocks and to spawning ground locations must be acquired in order to develop a precautionary approach in the Division 4S herring fishery. The following actions must be put in place to ensure the sustainability of the fishery and the conservation of herring:

5.1.1 Carry out the necessary work for the collection of data in order to develop a precautionary approach in the Division 4S herring fishery;

5.1.2 Protect spawning biomass and promote herring recruitment.

5.2 Habitat and ecosystem

Marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (OEABCMs) must be implemented to preserve species and their habitats. Specifically, the use of bottom-contact gear is prohibited in coral and sponge conservation sites. Moreover, the loss or abandonment of fishing gear at sea can have major impacts on the ecosystem. These impacts may include ghost fishing, entanglement (of sea turtles, marine mammals and seabirds) and alteration of the benthic environment. The management of the herring fishery must avoid undermining the conservation, protection and recovery of species at risk, other species likely to be impacted by fishing, and the environment.

In addition, injury and mortality related to interactions with fishing gear pose a serious threat to marine mammals. Interactions between these species and herring fishing activities are possible and may therefore be an issue in the recovery of some species. The lack of information about these impacts hinders the implementation of appropriate measures to reduce the impact of the herring fishery on the ecosystem. Through the monitoring of lost fishing gear, information can be collected to assess the extent of the problem.

5.2.1 Maintain and, where necessary, adjust conservation measures to reduce the impact of the herring fishery in protected marine and coastal areas;

5.2.2 Monitor lost or abandoned fishing gear to assess the extent of the problem;

5.2.3 Contribute to species at risk recovery strategies by maintaining and, where necessary, adjusting conservation measures to reduce the impact of the herring fishery on species at risk.

5.3 Fishery governance

Decision-making and collaboration between Aboriginal and non‑Aboriginal people are critical to ensuring sound governance of the herring fishery in Division 4S.

5.3.1 Promote collaboration between First Nations, non-Aboriginal fishers and the processing industry.

5.4 Economic prosperity of the fishery

The objectives below address the various issues related to the economic prosperity of herring fishers in Division 4S presented in Section 4.4.

5.4.1 Within DFO’s limits and mandate, support industry initiatives to develop marketing strategies and promote fishery products;

5.4.2 Within DFO’s limits and mandate, ensure equitable allocation of the resource, taking into account its proximity to communities, the reliance of coastal communities on the resource, and the fleet’s viability and mobility.

5.5 Compliance

Obtaining reliable, timely and accessible data on the fishery is critical to the conservation of the resource, in terms not only of target species but also bycatch and ecosystem components. Specific objectives for the Division 4S herring fishery must be defined to ensure proper monitoring of the fishery.

Compliance in the herring fishery is ensured by an adapted monitoring plan that makes it possible to adjust priorities according to the nature of offences. The focus of efforts by fishery officers to ensure compliance is highly dependent on the priorities identified each year. Raising fishers’ awareness to the importance of complying with regulations is an important component that promotes compliance from the start of the season.

5.5.1 Establish compliance monitoring objectives based on fishery monitoring requirements;

5.5.2 Adapt and, where necessary, adjust the surveillance and compliance monitoring plan according to conservation objectives and violations reports;

5.5.3 Raise fishers’ awareness of the importance of complying with resource conservation regulations.

6. Access and allocations

The Division 4S herring fishery is a competitive fishery, which means that fishers participating in this fishery can fish until the quota is reached. Therefore, there is no quantity of herring reserved for each licence holder. Since the early 1990s, a preventive quota of 4,000 t has been in effect for this area due to the lack of information on the status of the stocks.

7. Management measures

7.1 Total Allowable Catch (TAC)

When determining the TAC, Fisheries Management considers the scientific advice resulting from the herring stock assessment. Because of the lack of information on the herring fishery, the fishery has been managed by a preventive TAC of 4,000 t since the early 1990s, with no distinction made between the spawning groups.

7.2 Fishing seasons and areas

Although herring fishing in Division 4S is authorized from January 1 to December 29, licence holders must have valid licence conditions. Licence conditions are typically valid between April and December, but landings usually begin in late June and end in September.

To comply with Science’s guidelines with respect to the 2017 stock assessment, additional management measures were introduced to limit the fishing effort in the east end of Division of 4S and to protect the spawning period. These measures include a change in the authorized fishing period for seine licence holders. These measures are re-assessed annually.

7.3 Control and surveillance of removals

Gear authorized for use in the herring fishery includes purse seines (mobile gear) as well as gillnets and traps (fixed gear). Specifics related to the gear are set out in notices to fishers and conditions of licence.

All 4S herring fishers must complete the “combined form” logbook. Fishers with licences that allow the use of purse seines or traps are subject to dockside monitoring of their landings. Only purse seine fishers are required to have a vessel monitoring system that transmits their position every 30 minutes during herring fishing activities.

7.4 Requirements of the Species at Risk Act (SARA)

Pursuant to the Species at Risk Act (SARA), no person shall kill, harm, harass, capture, take, possess, collect, buy sell or trade an individual or any part or derivate of a wildlife species designated as extirpated, endangered or threatened. The species at risk in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence likely to be captured during herring fishery are: Spotted Wolffish, Northern Wolffish and Leatherback Turtle. Other species could be added during the year.

However, under section 83(4) of SARA, the recovery plans for species at risk listed above allow fishers to engage in commercial fishing activities subject to conditions. All bycatch of these species by fish harvesters must be immediately returned to the water and, if the fish is still alive, in a manner that causes it the least harm. Information related to species at risk catches must be reported in the “Species at risk” section of the logbook. Furthermore, information regarding interactions with all species at risk, including the species listed above as well as the North Atlantic Right Whale, the Striped Bass (St. Lawrence Estuary population), the Blue Whale (Atlantic population), the Beluga Whale (St. Lawrence Estuary population) and the Great White Shark must be recorded in the Species at Risk section of the logbook.

7.5 Habitat and biodiversity protection measures

In 2017, fishery closures were implemented as part of the Coral and Sponge Conservation Strategy for Eastern Canada. This strategy aims to protect coral and cold-water sponge species, their communities and habitats in the Atlantic region, including the estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. A total of 11 significant areas of coral and sponge concentration have been identified were selected for protection. The use of bottom-contacting fishing gear, including gillnets and traps used by herring harvesters, is prohibited as of December 15, 2017 in the coral and sponge conservation areas, some of which are found in NAFO Division 4S (n°15 herring fishing area) (Figure 10). These conservation areas also qualify as OEABCM and therefore contribute to national marine conservation targets. More details on each of these areas are available on our website.

These closures would have a negligible impact on the herring fishery in NAFO Division 4S. There is no overlap between these closed areas and the fishing grounds traditionally used by fishers as described in section 1.4.

Source: DFO, Quebec Region.

8. Shared stewardship arrangements

A herring stock assessment in Division 4S is scheduled every two years. An industry‑DFO advisory committee meeting is typically held after each stock assessment. Quebec’s North Shore fishing associations, processors and Aboriginal groups—which have formed a working committee on the development of a North Shore pelagic species fishery—participate in the advisory committee meetings and make recommendations to DFO on the management of the fishery. Workshops can also be held between stock assessments when the industry must be consulted on a new management measure. The recommendations of the advisory committees or workshops are transmitted in accordance with the process described in Section 1.6 on governance.

9. Compliance plan

9.1 Conservation and Protection (C&P) program description

The Conservation and Protection (C&P) Program promotes and ensures compliance with the acts, regulations and management measures for the conservation and sustainable exploitation of Canada’s aquatic resources and protection of species at risk, fish habitat, oceans and marine protected areas (Ex: corals and sponges).

Implementing the Program follows a balanced approach of management and enforcement, including:

- Promoting compliance with laws and regulations through education and shared stewardship,

- Inspection, monitoring and surveillance activities;

- Management of major case/special investigation in relation to complex compliance issues; and

- Compliance and enforcement Program capacity.

9.2 Delivery of the Regional Compliance Program

The C&P program is responsible, in whole or in part, for compliance and enforcement activities for all regional fisheries including, but not limited to, habitat, the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program (CSSP), marine protected area activities to ensure seabed protection, marine mammal protection, species at risk protection and all other activities related to the protection of aquatic species. Therefore, the amount of patrolling time allocated to a particular fishery is based largely on risk assessment for the resource and setting priorities. The C&P Branch surveillance efforts may vary from one year to another for a given fishery based on set priorities.

C&P monitoring activities of the herring harvesters in Gulf of St. Lawrence mainly focus on the catch, fishing gear compliance, compliance with conditions of licence and landings.

9.2.1 Catch and compliance with conditions of licence

C&P ensures compliance of fishing activities through its aerial surveillance program. During surveillance flights, herring fishing vessels are identified and their position is determined. The validity of fishing licences and conditions of licence is verified, including compliance with fishing area. Use of the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) is also verified. A video recording is made of each vessel observed during aerial patrols.

Through its mid-shore patrol vessel program, C&P also ensures compliance of fishing activities. Fishery officers on board patrol boats may board any fishing vessel they consider appropriate. During boardings, they check compliance of fishing gear, logbooks, catch size, bycatch, VMS operation, and any other relevant information related to fishing activity.

9.2.2 Landings

Fishery officers ensure herring fishers’ compliance by auditing landings, validating fishers’ logbook information and conducting any other relevant compliance audits related to the target fishery.

9.3 Consultations

C&P actively participates in the preparation and meetings of the Area 15 Herring Advisory Committee. C&P makes recommendations to resource managers on the development and implementation of management measures. Discussions or occasional working meetings are also held between DFO and fleet representatives. C&P also participates in informal interactions with all parties involved in the fishery on the wharf, during patrols or in the community to promote conservation.

9.4 Compliance performance

Surveillance efforts are generally shown as hours of work spent in the various fishing areas, number of at-sea interventions, number of boardings of vessels conducting fishing activity, and number of citations in comparison with the total number of interventions during the season.

C&P has also put in place a compliance follow-up program for the various fishing fleets. Aspects related to all forms of regulation violations are calculated and are used to generate a fleet compliance index.

9.5 Current compliance priorities

9.5.1 Compliance with fishing areas

Herring fishers have access to vast fishing areas. These areas are often shared with other types of fishing activity directed at species other than herring. Fishery officers ensure compliance with each fishery’s respective areas within a given sector.

9.6 Compliance issues

Daily updating of logbooks and recording of accurate data, as set out in the conditions of licence, are necessary for orderly management of the fishery. Logbooks are an important source of information used in assessing herring stocks, among other things. Fishery officers ensure follow-up of the information recorded in logbooks.

9.7 Compliance strategy

Dockside and at-sea checks are performed to ensure fishing compliance. Fishery officers regularly patrol the wharves before, during and after the fishing season. Meetings are held with fishers to go over the important points of regulations and conditions of licence, and to answer questions on how to interpret regulations. Fishing gear is checked for compliance. At all times, poaching incidents are given priority.

10. Performance review

This section of the IFMP defines the indicators that will assess progress towards the objectives identified in Section 5. A list of qualitative and quantitative indicators is proposed. Progress towards achieving the objectives based on the performance indicators for herring fishing area 15 is updated at each North Shore Small Pelagics Advisory Committee. Last update: May 18th 2021.

| Specific objectives | Performance indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Carry out the necessary work for the collection of data in order to develop a precautionary approach in the Division 4S herring fishery. | Percentage of work and studies mentioned in the Research section (section 2.7) of the IFMP completed. | From 6 projects and studies listed: 17% are completed, 33% are in progress and 50% are still planned. In detail:

Planned:

|

| Protect spawning biomass and promote herring recruitment. | Variation in spawning biomass of spring and fall stocks. |

Since 2018, the spring spawning stock biomass index in unit area 4Sw has been increasing. Fall spawning stock biomass index has remained relatively stable. A new year class (2017) was observed in 2020 in the spring component. A new year class (2016) was also observed in 2020 in the fall component. Number of potential spawning sites: a survey of anglers to identify the current location of major herring spawning grounds in 4S was conducted in 2019. Analyses are underway and a research paper presenting the survey results is expected to be published in 2021-2022. |

| Specific objectives | Performance indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Maintain, and adjust if necessary, conservation measures to reduce the impact of the herring fishery in protected marine and coastal areas. | Compliance with the prohibition of fishing in the closure areas for the protection of the corals and sponges; Adjustment of management measures that contribute to the achievement of the objectives of other marine protected areas. |

Since 2019 no violations for fishing in closed area and no adjustments required. |

| Monitor lost or abandoned fishing gear to assess the extent of the problem for this situation. | Documentation and reduction of the number of fishing gear lost or left at sea. | 2020 : Start contribution program for ghost gear recovery. No declaration for herring fishing area 15 since 2020. |

| Contribute to the objectives of species at risk recovery strategies by identifying existing conservation measures. These help to reduce the impacts of the herring fishery on species at risk by adapting existing measures or adding new measures where appropriate. | Number of conservation measures identified, adapted, or implemented in the management of the 4S herring fishery that contribute to the objectives of the species at risk recovery plans. | Measures currently in place:

|

| Specific objectives | Performance indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Promote collaboration between First Nations, non-indigenous fishers and the processing industry. | Number of consultative processes involving First Nations, non-indigenous fishers and processing industry stakeholders. | There is one advisory committee every two years and last ones were held in 2019 and 2021. Invitations are sent to all stakeholders from: First Nations, non-indigenous fishers, the small pelagic advisory committee and processing industry. |

| Specific objectives | Performance indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Within DFO’s limits and mandate, support industry initiatives to develop marketing strategies and promote fishery products. | Number of industry initiatives to improve marketing and promote fishery products. | In 20221 or 2022, there will be a meeting between industry and MAPAQ to see if they offer grant programs to support industry initiatives. |

| Within DFO’s limits and mandate, ensure equitable allocation of the resource, taking into account its proximity to communities, the reliance of coastal communities on the resource, and the fleet’s viability and mobility. | Number of NAFO areas actively harvested in the 4S commercial herring fishery to promote fishery products. | One sector (4Sw) of NAFO actively fished for the 4S commercial herring fishery. |

| Specific objectives | Performance indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Establish compliance monitoring objectives based on fishery monitoring requirements. | Number of monitoring objectives established. | Routine at sea patrol, dockside landing checks, VMS verification. |

| Adapt and, where necessary, adjust the surveillance and compliance monitoring plan according to conservation objectives and violations reports. | Annual update of the compliance enforcement plan. | The monitoring plan remained unchanged due to the low number of violations. 2019 : 2020 : |

| Raise fishers’ awareness of the importance of complying with resource conservation regulations. | Number of awareness-raising interventions. | At each inspection and advisory committee, fishermen are made aware of regulations. |

11. Glossary

Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK): knowledge that is held by and unique to Aboriginal peoples. It is a living body of knowledge that is cumulative and dynamic, and adapted over time to reflect changes in the social, economic, environmental, spiritual and political spheres of the Aboriginal knowledge holders. It often includes knowledge about the land and its resources, spiritual beliefs, language, mythology, culture, laws, customs and medicines.

Abundance: number of individuals in a stock or a population.

Age Composition: proportion of individuals of different ages in a stock or in the catches.

Biomass: total weight of all individuals in a stock or a population.

By-catch: the unintentional catch of one species when the target is another species.

Communal Commercial Licence: licence issued to Aboriginal organizations pursuant to the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations for participation in the general commercial fishery.

Division/sector: Area defined by NAFO in the Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries and described in the Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985.

Ecosystem-Based Management: taking into account species interactions and the interdependencies between species and their habitats when making resource management decisions.

Fish: As described in the Fisheries Act, fish includes:

- parts of fish,

- shellfish, crustaceans, marine animals and any parts of shellfish, crustaceans or marine animals, and

- the eggs, sperm, spawn, larvae, spat and juvenile stages of fish, shellfish, crustaceans and marine animals.

Fishing Effort: Quantity of effort using a given fishing gear over a given period of time.

Fishing Mortality: Death caused by fishing, often symbolized by the Mathematical symbol F.

Fixed Gear: Fishing gear other than mobile gear, angling gear, a drift net, a crab trap, a lobster trap or a dip net.

Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC): a fishery conducted by Aboriginal groups for food, social and ceremonial purposes.

Gillnet: fishing gear - a layer of net with weights at the bottom and floats at the top used to catch fish. Gillnets can be installed at various depths and are held in place by means of anchors.

Groundfish: species of fish living near the bottom such as cod, haddock, halibut and flatfish.

Homing: The behaviour of a species returning to the spawning ground where it was born.

Landings: quantity of a species caught and landed.

Management measure: Measure put in place to manage the fishery in order to ensure the conservation of the resource.

Mesh Size: size of the meshes of a net. Different fisheries have different regulations regarding minimum mesh size.

Mobile Gear: Trawls, purse seines and scallop drags.

Natural Mortality: mortality due to natural causes, represented by the mathematical symbol M.

Non-Aboriginal: In Canada, any person who is not of Amerindian or Inuit origin.

Otolith: structure of the fish's inner ear, made of calcium carbonate. Also called "petrotympanic bone" or "otocomy". Otoliths are examined to determine the age of fish, since annual growth rings can be counted. Daily rings are also visible on the otoliths of the larvae.

Pelagic: A pelagic species, such as herring, lives in midwater or close to the surface.

Population: group of individuals of the same species, forming a breeding unit, and sharing a habitat.

Precautionary Approach: set of agreed cost-effective measures and actions, including future courses of action, which ensures prudent foresight, reduces or avoids risk to the resource, the environment, and the people, to the extent possible, taking explicitly into account existing uncertainties and the potential consequences of being wrong.

Quota: portion of the Total Allowable Catch that a fleet, vessel class, association, country, etc. is permitted to take from a stock in a given period of time.

Recruitment: Amount of individuals becoming part of the exploitable stock e.g. that can be caught in a fishery.

Research Survey: Survey at sea, on a research vessel, allowing scientists to obtain information on the abundance and distribution of various species and/or collect oceanographic data. Ex: bottom trawl survey, plankton survey, hydroacoustic survey, etc.

Shared Stewardship: An approach to fisheries management whereby participants are effectively involved in fisheries management decision-making processes at appropriate levels, contribute specialized knowledge and experience, and share in accountability for outcomes.

Spawning group: sexually mature individuals from a stock.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The Act is a federal government commitment to prevent wildlife species from becoming extinct and secure the necessary actions for their recovery. It provides the legal protection of wildlife species and the conservation of their biological diversity.

Stock: Describes a population of individuals of one species found in a particular area, and is used as a unit for fisheries management. Ex: NAFO area 4S herring.

Stock Assessment: Scientific evaluation of the status of a species belonging to a same stock within a particular area in a given time period.

Tonne: Metric tonne, which is 1000kg or 2204.6lbs.

Total Allowable Catch (TAC): the amount of catch that may be taken from a stock.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge: a cumulative body of knowledge and beliefs, handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.

Year-class: individuals from the same stock who were produced in the same year, also known as a "cohort".

12. Bibliography

Brosset, P., T. Doniol-Valcroze, D. P. Swain, et al. 2018. Environmental variability controls recruitment but with different drivers among spawning components in Gulf of St. Lawrence herring stocks. Fisheries Oceanography, 28:1-17.

DFO 2002, Quebec North Shore Herring (Division 4S). DFO Sciences, Stock Status Report B4-02 (2002).

D. Tremblay et H. Powles (1982). Fishery. Biological characteristics and abundance of herring in NAFO Subdivision 4S, Canadian Atlantic Fisheries Scientific Advisory Committee, Research Document 1982/013.

DFO 2017. Assessment of the Quebec North Shore (Division 4S) Herring Stocks in 2016. Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2017/027.

Appendix 1: Changes in the number of herring fishing licences in Division 4S between 2010 and 2017, by gear type

Table 2 shows the number of active and inactive licences, the percentage of active licences by gear type and the total number of licences per year, between 2010 and 2017, for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal fishers in Division 4S. Table 3 shows the number of First Nations fishing licences for Division 4S herring. None of these licences were active between 2010 and 2017.

| Fishing gear | Licence | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gillnet | Active | 14 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Inactive | 214 | 217 | 213 | 212 | 209 | 206 | 205 | 201 | |

| Total | 228 | 225 | 225 | 223 | 217 | 210 | 208 | 204 | |

| % active licences | 6% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 2% | 1% | 1% | |

| Trap | Active | 6 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| Inactive | 17 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 14 | 17 | 20 | 19 | |

| Total | 23 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 14 | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| % active licences | 26% | 57% | 67% | 58% | 0% | 29% | 17% | 21% | |

| Eploratory purse seine | Active | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inactive | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| % active licences | 0% | 33% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Purse seine | Active | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| Inactive | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| Total | 9 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| % active licences | 11% | 22% | 44% | 73% | 36% | 64% | 73% | 55% | |

| Total licences per year | 264 | 260 | 260 | 259 | 243 | 246 | 244 | 240 | |

| Gear type | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gillnet | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

| Trap | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Exploratory purse seine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purse seine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

Appendix 2: Departmental contacts

| Name | Branch | Telephone | Fax | Email address |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoine Rivierre | Gestion de la ressource et de l’aquaculture | (418) 640-2636 | (418) 648-7981 | antoine.rivierre@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Andrew Rowsell | Directeur de secteur Côte-Nord | (418) 962-6314 | (418) 962-1044 | andrew.rowsell@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Jean Picard | Gestion de la ressource, de l’aquaculture et des affaires autochtones | (418) 648-7679 | (418) 648-7981 | jean.picard@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Dario Lemelin | Gestion de la ressource et de l’aquaculture | (418) 648-3236 | (418) 648-7981 | dario.Lemelin@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Sarah Larochelle | Affaires Autochtones | (418) 648-7870 | (418) 648-7981 | sarah.larochelle@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Yves Richard | Conservation et Protection | (418) 648-5886 | (418) 648-7981 | yves.richard@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Kim Émond | Sciences | (418) 775-0633 | (418) 775-0740 | kim.emond@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Martial Ménard | Services stratégiques | (418) 648-7758 | (418) 649-8003 | martial.menard@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Bernard Morin | Statistique et permis | (418) 648-5935 | (418) 648-7981 | bernard.morin@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

| Pascale Fortin | Communications | (418) 649-6297 | (418) 648-7718 | pascale.fortin@dfo-mpo.gc.ca |

Appendix 3: Safety of Fishing Vessels at Sea

Vessel owners and masters have a duty to ensure the safety of their crew and vessel. Adherence to safety regulations and good practices by owners, masters and crew of fishing vessels will help save lives, protect their vessel against damage and protect the environment. All fishing vessels must be seaworthy and maintained according to the regulations in force by Transport Canada (TC).

In the federal government, responsibility for navigation and regulations and inspections of ship safety is the responsibility of Transport Canada (TC), emergency response and rescue of the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), while Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is responsible for the management of fisheries resources. In Quebec, the Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité au travail (CNESST) has a mandate to prevent accidents and diseases work on board fishing vessels. All of these organizations are working together to promote culture of safety at sea and protection of the environment from the fishing community of Quebec.

The Standing Committee on the Safety of Fishing Vessels of Quebec, consisting of all the organizations involved in safety at sea, provides an annual forum for discussion and information for all matters related to the safety of fishing vessels such as design, construction, maintenance, operation and inspection of fishing vessels, as well as training and certification of fishermen. Any other topic of interest for the safety of fishing vessels and the protection of the environment can be presented and discussed. Fishers can also discussed security issues related to the management plan of the species (e.g. Fishery openings) in advisory committees held by DFO.

It is worth remembering that before leaving for a fishing expedition, the owner, master or operator must ensure that the fishing vessel is capable of doing its work safely. The critical factors of a fishing expedition include airworthiness and stability of the ship, possession of required safety equipment in good working board, crew training and knowledge of current and forecast weather.

- Date modified: