NAAHLS Research on Reportable Diseases - Shellfish Pathogens

Reportable diseases of aquatic animals are identified as diseases that would have a significant impact on the health of aquatic animals or to the Canadian economy. Under the Health of Animals Act, if an aquatic animal is known or suspected to be infected with a reportable disease, the person who owns or works with the animals is required by law to notify the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). These diseases may or may not occur in Canada; however, CFIA is obligated to notify the OIE immediately of a new occurrence of the disease in Canada or if the disease is found in a region of Canada where it did not previously occur. DFO NAAHLS laboratories are conducting research on the following reportable diseases.

Mikrocytos mackini (Denman Island Disease)

Denman Island disease is a reportable disease in Canada caused by an infection with the protozoan, Mikrocytos mackini. This protozoan occurs along the British Columbia coast throughout the Strait of Georgia and adjacent waters of Washington State, but confined to other localities around Vancouver Island. The disease is named after Denman Island where the protozoan was first detected. Several species of oyster are susceptible to Mikrocytos mackini, including the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), and European Flat oyster (Ostrea edulis). DFO’s NAAHLS lab at the Pacific Biological Station (PBS) in Nanaimo, BC is the National Reference Laboratory for this pathogen.

The World Organization of Animal Health has designated the NAAHLS laboratory at the DFO’s Pacific Biological Station as the International Reference Laboratory for Denman Island Disease (Mikrocytos mackini) of oysters. Gary Meyer leads all scientific and technical challenges relating to the pathogen. This includes providing scientific and technical assistance and expert advice on topics linked to surveillance and control of the pathogen nationally and internationally.

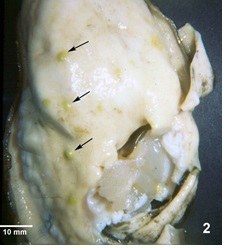

Crassostrea gigas removed from shell and illustrating lesions (arrows) observed during later stages of Denman Island disease. Typically, Mikrocytos mackini can no longer be found in oysters at this advanced stage of the disease.

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Ostrea edulis with top valve removed, illustrating numerous lesions in the adductor muscle (arrow) caused by Mikrocytos mackini.

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Haplosporidium nelsoni (Multinucleated Syndrome X (MSX))

The first occurrence of MSX in Canada was discovered in the Bras d’Or Lakes on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia in 2002 following heavy mortalities in oysters (Crassostrea virginica). The World Organization of Animal Health was immediately notified of the positive MSX finding. Although the disease is known along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States, shellfish surveys in the four Atlantic Provinces from 1990 to 2001 did not find MSX. It is not known exactly how the MSX pathogen found its way to the Bras d’Or Lakes, but strict movement controls of shellfish from the Bras d’Or Lakes and three sites at the eastern-most tip of Cape Breton, Aspy Bay, St-Ann’s Harbour and MacDonald’s Pond were implemented to prevent the spread of the pathogen. In 2013, the pathogen remains confined to these areas.

Histological section through the digestive gland of Crassostrea virginica from Virginia, USA, infected with Haplosporidian nelsoni. Multinucleate plasmodia (P) occur in connective tissue while the release of mature spores (S) are limited to the digestive tubule epithelium.

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Haplosporidium nelsoni is a parasite that causes significant disease causing mortality of oysters, Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and is a reportable disease in Canada. The parasite is found along the US eastern seaboard from Florida to Maine, and it was found in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia in 2002. It is also found in Japan and Korea. The disease is restricted to salinities over 15 ppt and rapid, high mortalities in oysters occur at salinities of 18-20 ppt. Parasite proliferation is greatest above 20 ppt, but the parasite cannot survive salinities below 10 ppt. There is some evidence that water temperatures greater than 20ºC may cause the disease to disappear. DFO’s NAAHLS lab in the Gulf Fisheries Centre (GFC) is the National Reference Laboratory for this pathogen.

The methods used in NAAHLS to detect MSX include histopathology, quantitative PCR (qPCR), and conventional PCR and were validated by the GFC in consultation with Dr. Carol McClure of the Atlantic Veterinary College. Additional testing, such as in-situ hybridization and sequencing are also used to confirm the species. Suspected positive findings are confirmed at the GFC reference lab.

MSX Disease of American (Eastern) Oysters

Oyster soft tissues removed from shell (bottom left) and "steak" cut for microscope examination: spores in digestive gland (top right), plasmiodial stage in gills (bottom right)

What is MSX Disease?

This disease is caused by a microscopic parasite – too small to see with the naked eye – with the scientific name Haplosporidium nelsoni. MSX stands for "Multinucleate Sphere X" which was what the parasite was first called when discovered in Chesapeake Bay American (or Eastern) oysters (Crassostrea virginica) in the late 1950s.

Does it affect Human Health?

No. MSX is purely a health problem for the American oysters. In the United States, oysters are routinely marketed from populations that carry MSX with no human health concerns.

What does it look like?

Under a microscope, two stages of MSX can be detected in the oyster tissues:

- the ‘plasmodium' which is the multinucleate stage that spreads throughout the tissues and earned the parasite the name MSX; and

- the spore stage, which develops in the walls of the digestive ducts of the oyster.

Where does it occur normally?

MSX has been reported from Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) in Korea, the Pacific coast of the US, and from France. However, MSX does not cause serious disease in this species of oyster. In American oysters, however, it causes mass mortalities and has seriously impacted eastern US stocks in Chesapeake Bay. It occurs from Maine south to Florida, but most serious disease losses occur in the Chesapeake-Delaware Bay area.

What does it do to the Oyster?

When the parasite enters the oysters tissues it multiplies and spreads. The plasmodial stages can be found throughout the soft tissues, but by the end of the summer spore stages start to develop in the walls of the digestive tubules. All this causes tissue damage and gradual weakening of the oysters until they start dying at the end of the summer. Some infected oysters may survive over winter but fail to recover the following spring so a second wave of mortality can be observed then. Oysters that have survived mass mortalities show no further signs of infection until the appearance of the plasmodial stage of MSX the following summer.

How does it spread?

MSX cannot be spread directly from oyster to oyster, but is readily picked up by some unknown agent in the water. It is believed that MSX uses an unknown, intermediate host to spread infection. Oysters that have been exposed to salinities of 10 ppt and temperatures of 20 C over a period of two weeks appear to lose their infections. Holding oysters in salinities of less than 15 ppt may suppress the disease but not necessarily kill the parasite.

Does it affect any other shellfish?

There is no evidence that MSX can cause disease in other bivalve molluscs, such as clams, mussels and scallops. However, MSX could be accidentally carried on or in other shellfish, thus, caution is required when moving any shellfish from affected areas.

SSO Disease of American (Eastern) Oysters

Oyster soft tissues removed from shell (bottom left) and “steak” cut for microscope examination: spores stain pink in connective tissue (bottom right), plasmodial stage in connective tissue (top right)

What is SSO Disease?

This disease is caused by a microscopic parasite – too small to see with the naked eye – with the scientific name Haplosporidium costale. SSO stands for “Seaside Organism” since it was first found in oysters on the ocean side of Virginia, unlike MSX (a closely related oyster disease) that is found in estuarine waters.

Does it affect Human Health?

No. SSO is purely a health problem for the American oysters. In the United States, oysters are routinely marketed from populations that carry SSO with no human health concerns.

What does it look like?

Under a microscope, two stages of SSO can be detected in the oyster tissues:

- the ‘plasmodium', which is a multinucleate stage that spreads throughout the tissues, is very similar to the plasmodium of MSX – but slightly smaller; and

- the spore stage, which develops in the connective tissues, unlike the spores of MSX that develop in the walls of the digestive ducts of the oyster.

Where does it occur normally?

SSO has been found solely in American oysters between Long Island Sound, New York to Cape Charles, Virginia, in waters over 25ppt salinity.

What does it do to the Oyster?

When the parasite enters the oysters' tissues it multiplies and spreads. The plasmodial stage first appears in early summer (May to June). By late June/July, spores develop throughout the connective tissues, and it is at this stage of infection that mortalities are observed. An oyster mortality rate of up to 40% has been reported in the USA.

Some oysters may survive infection, but the SSO parasite is difficult to detect until the following spring. This differs from MSX in two ways:

- MSX spores develop gradually throughout the summer and are located in the digestive tubules;

- and MSX causes two waves of mortality – one in late summer and another in late spring.

How does it spread?

SSO cannot be spread directly from oyster to oyster, but is picked up from some unknown stage in the water. It is believed that SSO uses an unknown, intermediate host to spread infection. Oysters exposed to salinities of less than 25 ppt do not appear to be susceptible to SSO, as infections appear limited to higher salinities.

Does it affect any other shellfish?

There is no evidence that SSO can infect other bivalve molluscs, such as clams, mussels and scallops. However, SSO could be accidentally carried on or in other shellfish, thus, caution is required when moving any shellfish from affected areas.

Who should I call if I find dying oysters?

If you find dying oysters, do not move them. Report them to one of the following contacts:

- DFO Mary Stephenson (506) 851-6983

- DFO Anne Veniot (506) 851-3107

For more information:

White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSv)

White Spot disease, Yellow head disease and Taura syndrome virus are a few of the many exotic crustacean diseases that are caused by viral pathogens. Crustaceans include shrimp, crayfish, crab, and lobster. These diseases can affect a wide range of crustacean species both in the countries of origin and in crustacean species elsewhere in the world; none of these diseases have been reported in any Canadian crustacean species even though these disease agents have slowly spread throughout much of the world.

White Spot Disease was first reported in Northeast Asia in the early 1990's. It has since been found in South America, the United States, Southeast Asia, and India and is potentially devastating to native wild shrimp species and shrimp farms due to the high morbidity and mortality it can cause. It is a reportable disease in Canada. White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSv), also known as White Spot Disease (WSD), is a viral pathogen that affects many species of tropical shrimp and one of the first pathogens to be studied at the Charlottetown Aquatic Animal Pathogen and Biocontainment Laboratory (CAAPBL).

Link to OIE: http://www.oie.int/index.php?id=171&L=0&htmfile=chapitre_wsd.htm

NAAHLS Research on White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSv)

White Spot Disease has not been reported as causing an infection or disease in any Canadian crustacean species. However, to satisfy international trading partners that Canadian exports of crustacean products (especially lobster) are free of White Spot Disease, Dr. Phil Byrne at DFO’s DFO's Gulf Biocontainment Unit – Aquatic Animal Health Laboratory (GBU-AAHL) has carried out research on shrimp and lobster to develop testing procedures that can accurately determine the presence or absence of the virus in lobster, as well as other Canadian crustacean species. In addition, the potential susceptibility to White Spot Disease of crustacean species that are found in Canada is currently being investigated using challenge studies. This work is being done in collaboration with researchers at the Lobster Science Centre at the University of Prince Edward Island's Atlantic Veterinary College and Dr. Mark LaFlamme at the Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Gulf Fisheries Centre – Aquatic Animal Health Laboratory (GFC-AAHL), in Moncton, New Brunswick. Tests for other disease agents that infect tropical shrimp are also being developed by GBU-AAHL and GFC-AAHL.

Taura Syndrome Virus (TSv) and Yellowhead Virus Disease (YHD)

TSV and YHD are two tropical shrimp viruses that like White Spot Disease are recognized as widespread disease-causing agents of tropical shrimp throughout much of Southeast Asia, Central and South America, and other areas. TSV and YHD are both reportable diseases in Canada, but do not occur in Canada.

NAAHLS Research on Taura Syndrome Virus and Yellowhead Virus Disease

Live animal based work supporting diagnostic test development, similar to that of WSD, has taken place by Dr. Phil Byrne at DFO’s DFO’s Gulf Biocontainment Unit –Aquatic Animal Health Laboratory (GBU-AAHL) involving shrimp and lobster. Mark Laflamme at DFO’s Gulf Fisheries Institute in Moncton then used inactivated samples material from the GBU-AAHL work to develop and validate molecular test methods for these viruses.

- Date modified: