(DRAFT) Steps to implement the fishery monitoring policy

(DRAFT) Steps to implement the fishery monitoring policy

(PDF, 516 KB)

Box 1: Implementing the policy in Indigenous fisheries

Decisions flowing from the application of this policy must respect the rights of Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, including those through land claims agreements.

1. Introduction

This document provides guidance to resource managers and others on implementing Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO) fishery monitoring policy. This document lays out six procedural steps to achieve the policy objectives.

2. Procedural Steps for Fishery Monitoring Decision Making – In Summary

This section provides a quick reference for the Six Steps that must guide fishery monitoring decision making across all federally managed Canadian fisheries, with key terms defined on the following page. See Section 3 for detailed guidance.

Step 1 – Prioritize fisheries for assessment

|

Step 2 – Assess the monitoring program

|

Step 3 – Set monitoring objectives

|

| Step 4 – Specify monitoring requirements |

Step 5 – Operationalize the monitoring program |

Step 6 – Review the monitoring program periodically and re-assess as required |

Figure 1: Procedural steps to implement the fisheries monitoring policy

Fishery monitoring policy objective:

to have a consistent approach to establishing fishery monitoring requirements across fisheries, by following a standard set of action steps.

Key terms used in the preceding summary are defined as follows:

1 fishery objectives – specific and measurable objectives developed by fisheries managers to address management issues e.g., those related to the target species and ecosystem concerns

2 risk factor - area of potential exposure to risk related to conservation or compliance, e.g., stock status of target species, impact on retained bycatch species, impacts on habitat structure or composition, occurrence of misreporting, etc.

3 dependability –measures how well catch monitoring tools provide data from which actual catches can be inferred. Dependability increases with accuracy and precision and is also a function of an estimate’s proximity to a set reference point e.g., total allowable catch.

How dependability ensures monitoring programs are “fit for purpose”

Investing in data quality to improve accuracy and / or precision does not always improve dependability. Where catches are small relative to the compliance limit, such investments only increase cost. It is only where catches approach the limit that high quality data translates to dependability. In reviewing monitoring programs, assessors consider risks and examine estimates to see if they are of sufficient quality to be dependable. They can then assign monitoring resources where risks (e.g., TAC overages) are highest.

4 data quality – a measure of how well the monitoring program estimates the quantity of interest, e.g., estimated removals of species X versus actual removals. Being both accurate (low bias) and precise (low variance), high quality data will produce estimates with a high likelihood of being close to the true value.

5 parameter - specific quantity being measured within each risk factor, e.g., weight of retained bycatch of species X. Where there are multiple parameters (e.g., multiple bycatch species), the risk screening tool will need to be run multiple times.

6 Risk screening tool – high-level screen of the risks a fishery poses to risk factors, identifying risk areas that may require changes to the monitoring objectives and program. It does not assess dependability or quality, or prescribe monitoring tools and/or coverage levels.

7 estimate – statistical value derived from sample data to estimate the value of a corresponding population parameter (e.g., catches of target and non-target species).

8 monitoring objectives – describe the target or desired state of the monitoring program. They need to:

- establish goals for monitoring programs

- address gaps in programs highlighted by dependability and risk review

- guide the selection of monitoring approaches, tools, and coverage

9 data: the information collected about the catch and other information collected via the reporting and monitoring tools used as part of a fishery’s monitoring program

3. Procedural steps for fishery monitoring decision making – additional guidance

This section provides detailed procedures, together with explanations and examples where appropriate, to guide resource managers and others through the six steps summarized in section 2.

3.1 Prioritize (Step 1)

Lead(s): Regional DFO - Fisheries Management, DFO - Science, and DFO - Conservation and Protection.

Support: DFO NHQ – Fisheries and Harbour Management.

In consultation with harvesters, DFO Regions should perform an initial triage to prioritize fisheries for policy application. This prioritization could be based on, but is not limited to, the following factors:

- The results of any previously completed risk review;

- Known conservation or compliance risks;

- Market access requirements;

- International obligations;

- Treaty obligations;

- Industry support/interest/capacity;

- Technical feasibility/ease of implementation; or

- Number of licence holders and conditions of licence.

Based on the results of this triage, each region will develop a work plan to apply the policy to priority fisheries. The plan should include priority actions and timelines and be developed in collaboration with relevant DFO sectors, regions, and stakeholders, as appropriate. All fisheries will eventually be examined according to priorities.

3.2 Assess the monitoring program (Step 2)

Lead(s): DFO - Fisheries Management, DFO - Science, and DFO - Conservation and Protection.

Support: Harvesters, DFO NHQ - Fisheries, and Harbour Management.

In preparation for assessing prioritized fisheries, managers will need to consolidate data and information including, where available, the use of existing publications, the engagement of traditional and local ecological knowledge, and other expert opinion. The assessment should be done in collaboration with harvesters, where appropriate, and documented for transparency and for future review. There are five parts to performing the assessment.

Part 1: Determine assessment unit (e.g., fishery or fleet), and describe the fishery, the management regime, and the fishery objectives (section 3.2.1) |

Part 2: Document existing monitoring program, e.g., data and information collected, reporting and monitoring tools, tool coverage level, etc. (section 3.2.2) |

Part 3: Assess dependability and data quality for each component of catch (section 3.2.3) |

Part 4: Assess both conservation and compliance related risk factors using the risk screening tool (section 3.2.4) |

Part 5: Perform gap analysis for each fishery / fishery unit (section 3.2.5):

|

Figure 2. Assessment phases for determining data quality, estimate dependability, and risk categories giving the required level of dependability for each parameter estimate.

Figure 2 outlines the main phases involved in assessing data quality, dependability, and risk. Part 1 identifies the assessment unit whose monitoring program will be assessed in Parts 2 to 4. Determining the dependability and data quality of the available data in the fishery is central to identifying if the data is sufficient based on the risk the fishery poses. Part 5 involves a gap analysis to determine the level and type of monitoring needed to address conservation and compliance risks and to meet the dependability and data quality requirements for the fishery.

3.2.1 Determine the assessment unit, fishery description, management regime, and

fishery objectives

Assessment unit

Part 1 of the assessment includes selecting the right unit of assessment. It could be a fishery or a fishery sub-unit. With larger fisheries the “fleet” might be the appropriate unit, as vessel, gear, and other differences between fleets can lead to different risks to the resource making monitoring requirements fleet-specific. Fishing area might be a better unit, especially with fisheries broken into management units (e.g., Crab Fishing Areas) for science and management purposes.

Fishery description

Assessors need to pull information from the integrated fisheries management plan (IFMP) and other sources as necessary to assemble a description of the assessment unit that includes licensing details (DFO management area, license type), and other basic details of the fishery such as species fished, vessel and gear used, timing of the fishery, size of the fishery, and harvesters’ organization(s).

Management regime

Describing the management regime helps the assessors to understand the regulatory / policy approaches and management measures used to control fishing activity. Examples include competitive versus individual quota fisheries, and fisheries managed via effort controls versus those managed via limiting removals. Management regime will play a significant role in determining monitoring approaches (e.g., monitoring traps versus catches and landings.).

Some management regimes are more complicated to administer. Fisheries of higher complexity often have greater conservation and compliance requirements. Refer to section 3.3, Setting monitoring objectives, for more guidance on complexity.

Fishery objectives

Monitoring programs should be designed to support the fishery objectives set out in the IFMP. For each unit, assessors must list the fishery objectives including those related to resource management, enforcement and science. Both long-term objectives, e.g., “Long-term, sustainable shrimp fishery in SFA 13-15”, and short-term objectives, e.g., “Keep fishing mortality at or below 20% of spawning stock biomass (healthy zone)” may be found in an IFMP. The short-term fishery objectives are more relevant to this exercise, as monitoring can only track progress towards measurable objectives.

Box 2: Three types of objectives to consider

Fishery objectives promote the sustainable use of fisheries resources. They are captured in IFMPs and guide fisheries planning in areas ranging from stock conservation and ecosystem approaches to other aspects of sustainable fishing such as shared stewardship and regulatory compliance.

Policy objectives, together with the policy principles, are found in the Fishery Monitoring Policy and guide the effective implementation of the policy.

Monitoring objectives state the goals that a monitoring program aims to achieve, and provide direction to monitoring activities, e.g., by setting targets for coverage levels.

The assessment should include all conservation and compliance fishery objectives, such as those related to:

- Total target catch (including discards),

- Bycatch (retained and non-retained),

- SARA species;

- Habitat; and

- Enforcement.

In addition to explicitly stated fishery objectives, consider whether other drivers are in place that require fisheries data, e.g., international agreements, treaty requirements, and other considerations.

3.2.2 Document existing monitoring program

Describe the current monitoring program requirements for each unit, e.g., parameters of interest, data and information collected, parameter estimation process, reporting and monitoring tools, tool coverage level, etc. Examples of monitoring requirements include At-Sea Observation coverage levels, logbook returns, hail-ins, hail-outs, and Dockside Monitoring requirements, to name a few. Consult with Resource Management to obtain the target monitoring level and the actual achieved level of monitoring.

3.2.3 Assess dependability and data quality for each parameter of interest

For each unit, assess the adequacy of the data collected by the existing monitoring program for catches, ecosystem impacts, compliance, and other parameters of interest. Questions to consider include:

- Which sets of data from 3.2.2 are currently used to measure progress towards the fishery objectives? For example, to support a TAC objective, does the program provide estimates of catch by weight? How often? What is known currently about the quality of this data?

- How is the data used? Is some data not used, and if so why?

- Is the data quality and dependability adequate to achieve the data requirements for each of the parameters that are estimated, to fully support the fishery objectives? Assess:

- Type of data collected, the frequency, the data format;

- Adequacy of the data collected in terms of dependability, accessibility, and timeliness

For monitoring catches of target species and bycatch species, DFO is developing a methodology to assess the dependability of information derived from catch monitoring programs. It will evaluate whether a monitoring program is adequate by determining if information is of sufficient dependability and quality for its intended use.

One on the main uses of fisheries data is to estimate catches. A single parameter (e.g., total catch) and the monitoring program(s) required to estimate it is termed a parameter estimation process. Two interrelated concepts, quality and dependability, are used to quantify the degree to which a parameter estimation process is achieving its objective.

The quality of a parameter estimation process describes how close to the true value (e.g., actual total removals of species X) the parameter estimate (e.g., estimated total removals of species X) is likely to be. The quality of the estimation depends on its accuracy (converse: inaccuracy or bias) and its precision (converse: imprecision or variability).

Fishery monitoring policy objective:

to have dependable, timely and accessible fishery information necessary to help ensure that Canadian fisheries are managed in a manner that support the sustainable harvesting of aquatic species.

The dependability of a parameter estimation process describes its ability to help reach the objective for which it is to be used, such as to determine whether a quota has been reached. Dependability is a function of the quality of the parameter estimation process and the objective.

The dependability of data and resulting estimates can be stated qualitatively: e.g., low dependability, not timely, not accessible, not adequate due to data format issues, etc. Assessors are to document these results, providing a determination of dependability of estimates for each component of catch, for each fishery / fishery unit.

The sample design for collecting data will also impact dependability. Catch estimates based upon a census (100% coverage) are usually highly dependable. More often, however, catch estimates are based upon a survey (partial coverage), where a sample of the statistical population is observed. In such cases, data collection should use a proper statistical sampling protocol. This will enhance data quality by increasing precision and accuracy making estimates derived from the sample data more dependable.

Finally, the assessment of dependability needs to account for the possibility of biased data. Biases can be intentional (e.g., underreporting catches or landings, or discarding protected species without reporting them) or unintentional (e.g., uncorrected deviations from the sampling design, such as unplanned non-random sampling). The following options are available to mitigate against biased data:

- Designating accredited third party service providers to provide dockside monitors and at-sea observers

- Combining monitoring approaches to enable cross-checking / auditing of self-reported data

- Continuing to collaborate with indigenous communities on ways to ensure effective monitoring and dependable data in FSC fisheries.

Output: Indicator of estimator dependability for each catch component

Where habitat impacts, or other ecosystem components apart from those related to catch, are captured as monitoring objectives, a methodology is needed to determine data quality, as we have for target and non-target catches.

Output: Indicator of data quality for each non-catch component

3.2.4 Assess both conservation and compliance related risk factors using the risk screening tool

DFO has developed a qualitative “risk screening tool” which analyzes the risk a fishery poses to specific conservation factors, as well as the occurrence of non-compliance. A full description of the methodology and tool can be found in the risk screening tool guidance document.

The risk screening tool has two distinct outputs:

Output 1: Conservation Risks

The tool will score the risk the fishery poses to seven conservation risk factors related to target species, bycatch species, community, and habitat. The qualitative scoring will determine the risk category for each conservation risk factor - low, medium, or high. Each risk category prescribes general requirements for the quality of information necessary to identify within monitoring objectives. In the case of catch data, the risk level will also indicate the level of required dependability (see Table 1).

| Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|---|

Improvements to the precision and accuracy of estimate may not be needed While there is a low risk of not meeting the objective, the fishery dependent reporting must provide adequate information* to estimate catch for the purposes of meeting the objective for the component * guidance regarding “adequate information” to be determined |

The monitoring program should be such as to produce an estimate of catch and non-retained catch for which the precision is sufficient to have a reasonable likelihood* of being able to determine whether the objective for the component is being met The sampling design is such that accuracy is as high as possible and bias is limited * guidance regarding “reasonable likelihood” to be determined |

The monitoring program adopted should be such as to produce an estimate of catch and non-target catch for which the precision is sufficient to have a high likelihood* of being able to determine whether the objective for the component is being met The monitoring program should include as close to a full census of catch and non-retained catch as possible, with sampling design demonstrated to have high accuracy and known to be theoretically unbiased * guidance regarding “high likelihood” to be determined |

Table 1

Table 1 identifies the three categories that fisheries can be grouped into based on the risk they pose. Each category describes the nature of the data required from a catch monitoring program, which must be of sufficient dependability to address the level of risk posed.

Output 2: Occurrence of non-compliance

The compliance function of the tool scores the occurrence (or frequency) of non-compliance in the fishery related to misreporting, use of illegal gear, and fishing in closed areas or at closed times. Occurrence will receive a qualitative scoring from “no known issues” to “regularly occurs”. All relevant compliance factors must be scored, even those that do not fit exactly into one of the three categories. There might be a licence condition for harvesters to release bycatch fish directly to the water without delay. This could be scored under “use of illegal gear” even though the issue is fish handling practices, not illegal gear.

Data used for this review could come from many sources, including but not limited to:

- At-Sea Observer reports or data from other monitoring tools;

- Expert judgement;

- Investigations; or

- Scientific analyses.

Both outputs must be documented, providing qualitative conservation and compliance risk scores for each risk factor, for each parameter, for each assessment unit.

3.2.5 Perform gap analysis for each fishery / fishery unit

The purpose of this final stage in the assessment is to interpret the assessment results and identify gaps left by inadequate or missing data on key risk factors from section 3.2.4. This is also where we determine if data dependability and / or quality align with the identified risk categories per section 3.2.3. Finally, the gap analysis needs to consider the complexity of the management regime, as discussed in section 3.2.1.

Fishery monitoring policy objective:

To obtain information on effort, total catch (retained and non-retained) and other ecosystem components, as required.

The outcome of the gap analysis should inform fishery managers whether changes are needed to:

The current monitoring objectives,

- the minimum data requirements, and

- the overall monitoring program.

3.3 Set monitoring objectives (Step 3)

Lead(s): DFO - Fisheries Management

Support: DFO - Science, DFO- Conservation and Protection,

others as applicable

Box 3: Some fishery-specific factors to consider in setting monitoring objectives:

- Biological characteristics – stock, age, sex, length/weight, flesh colour, marks / tags, etc.

- Condition of releases / proper handling practices for non-retained catch

- Fishing in closed areas

- Encounters with coral and sponge

- Proper setting of longlines and trawls

- Proper use of selectivity gear

- At-sea processing, ITQ management, longer duration trips, and other “complexity” factors

In consultation with harvesters, managers must now use the results of the analysis from Step 2 to adjust or create monitoring objectives to address the identified gaps. These will guide the selection of monitoring methods, tools, and tool coverage for a fishery monitoring program. Refer to the fishery objectives and current monitoring programs detailed out in sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2. Ensure all relevant and necessary monitoring objectives are in place, particularly those pertaining to conservation and compliance. Typical monitoring objectives will stem directly from the fishery objectives, monitoring fishery characteristics related to the following:

- Total catch of target species (including discards),

- Total catch of bycatch species (retained and non-retained),

- Fishing effort (number of harvesters and/or units of gear, gear type/details, location and length of time fished)

- Incidental catch of SARA species;

- Habitat Impacts; and

- Enforcement.

Fishery-specific knowledge is needed to ensure monitoring objectives are comprehensive. Box 3 provides some examples fishery specific factors that may be critical for the fishery being assessed.

In addition, objectives need to consider complexity drivers such as international agreements requiring specific data, or treaty requirements. Complex fisheries may dictate an increased level of monitoring, which must be reflected in the objectives, e.g., calling for as close to a full census of fishing activity as possible, rather than survey coverage. Appropriate monitoring will provide the information needed for estimates of greater dependability to account for complex fisheries. Characteristics that increase complexity of a fishery include:

Box 4: Different kinds of monitoring objectives

Monitoring objectives need to cover a broad range of fisheries inputs:

Fisheries monitoring objective - Close areas if bycatch is higher than 5% during a fishing day. Use data from At-Sea Observer Program daily reports.

Science monitoring objective - Determine the weekly number, weight and identification of corals and sponges caught in Area Z.

Compliance monitoring objective - Ensure compliance with reporting via logbooks as per license conditions.

- The number of stocks or species targeted and caught by the fishery;

- Trip length;

- At sea-processing; and

- Management regimes that require more timely monitoring and reporting (e.g., Individual Transferable Quota fisheries).

Finally, monitoring objectives must align with the fisheries monitoring policy objectives (see boxes).

3.3.1 Conservation monitoring objectives to reflect conservation risk factors

Conservation monitoring objectives should now be set that reflect the level of risk the fishery poses to conservation factors as determined by the risk screening tool in Step 2. The assigned risk categories prescribe general requirements on the dependability and / or quality of information.

As a general rule, the desirable level of data quality (precision and accuracy) will depend on the degree of impact a fishery has on target species, bycatch species, community, and habitat. As the impact of the fishery on these risk factors increases, conservation monitoring objectives will demand data of higher quality. Alternatively, if the impact of a fishery on these factors is low, then high quality data may not be necessary to meet the objective. The conservation monitoring objectives must clearly indicate the required level of quality and dependability (in the case of catch data).

3.3.2 Compliance monitoring objectives to reflect the occurrence of non-compliance (DFO - C&P lead)

As a result of the monitoring program assessment in Step 2, DFO - Conservation and Protection must decide what compliance monitoring objectives are required to address misreporting, use of illegal gear, and fishing in closed areas or at closed times.

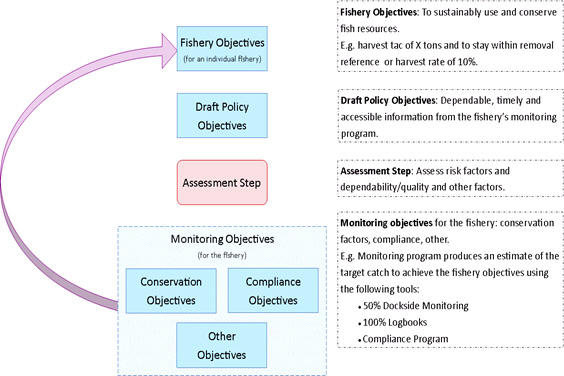

Figure 3: Setting monitoring objectives for a fishery

Figure 3 outlines in general terms how monitoring objectives are developed. Fishery objectives reflect the goals to be attained through the management of the fishery, e.g., measures to control harvest levels. Draft policy objectives are the requirements highlighted in the policy pertaining to data dependability, timeliness and accessibility. The assessment of the fishery objectives in relation to the objectives from the policy help to inform the development of monitoring objectives for the fishery. These monitoring objectives are concrete targets for catch monitoring measures for a fishery. For example, this process could determine that a fishery requires 50% dockside monitoring coverage to meet the objectives of the fishery and the policy.

3.3.3 Collectively setting monitoring objectives and documenting them in IFMPs

DFO and harvesters must consider all conservation, compliance, and other relevant objectives (e.g., related to complexity) to establish the monitoring objectives for a fishery. The following should be considered before finalizing monitoring objectives:

- Are there opportunities for trade-offs between objectives?

- Given the limitations in financial and operational resources, can objectives be combined?

Box 5: Using SMART criteria for monitoring objectives

- Specific – Clearly articulated, well-defined, and focused;

- Measurable – Able to determine the degree to which there is completion or attainment;

- Achievable – Realistic and practical; attainable within operational constraints dependent on resource availability, knowledge, and timeframe;

- Relevant – Tied to the overarching policy or other program objectives; and

- Time-bound – Contains clear deadlines

For example, a conservation objective related to timely reporting to inform in-season closures for bycatch might be combined with an objective to have timely reporting to help implement quota transfers in ITQ fisheries.

The development of monitoring objectives should be communicated and implemented through the Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) process or through other fishery planning processes such as those used for Indigenous fisheries and recreational fisheries.

3.4 Specify monitoring requirements (Step 4)

Lead: DFO - Fisheries Management.

Support: DFO Science, DFO Conservation and Protection, harvesters, contractors, others if applicable.

In this step, fishery managers must determine which combination of data collection methods, tools, and the tool coverage levels will meet the minimum data requirements to reliably estimate relevant parameters. This step must also include an assessment of the information management system needs.

3.4.1 Data collection methods, tools, and tool coverage levels

In general, there are two methods for collecting fishery data: at-sea data collection or dockside data collection. The data collection tools used for each method can be divided into two varieties:

- Fisher-dependent tools, e.g., logbooks, commercial sales slips, hail-ins/hail-outs, harvesters/creel surveys, fish harvester collected biological samples; and

- Fisher-independent third-party collected/verified tools, e.g., aerial gear counts, on-water gear counts, video monitoring systems, at-sea observers, dockside monitoring.

The main limitation of a fishery-dependent data collection method is the lack of an independent means of validation, especially where there are disincentives to report. This can occur when the time and effort required to accurately report data, rare events, or interactions with protected species are likely to negatively impact operations of the vessel. The perceived lack of usefulness for the data may also present a disincentive to reporting.

Box 6: A Mix of monitoring tools and approaches

To achieve the required quality and dependability of data, combining monitoring approaches (i.e. both fisher-dependent and independent) is often necessary. The integration of fisher-dependent tools with independent monitoring allows for cross-checking and auditing of self-reported data. Combining tools can enhance the ability of an individual tool to meet specific management and data needs. For example, combining fisher-dependent logbooks with fisher-independent at-sea observers or video monitoring can compensate for quality issues in the logbook data.

Coverage levels need to be understood in terms of statistical populations, e.g., the set of all fishing trips of a particular fishery during a season. Program sampling design can be based upon a survey (partial coverage), where a sample of the statistical population is observed, or a census (100% coverage) where the whole statistical population is observed. These observations are used to estimate a parameter, such as the total annual catch of a target species by that fishery.

For an overview of monitoring tools in the typical contexts in which they are employed in Canada, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses, managers can consult A Review of Fishery Monitoring Tools used to Record Catch Data in Canada (B. Beauchamp, H. Benoit, and N. Duprey, 2017).

3.4.2 Requirements to support conservation monitoring objectives

The monitoring program assessment laid out in section 3.2., specifically the risk screening tool and the analysis of the adequacy of data/estimates, should help managers in selecting of the right mix of methods, tools, etc., to support conservation monitoring objectives. The risk screening tool allows managers to assign monitoring resources to those conservation risk factors where it is needed. The dependability methodology should provide guidance and quantitative rigor for the selection of tools and other monitoring requirements that will yield the data needed to produce estimates of sufficient data dependability. See Table 1 in section 3.2.4 for more guidance on how the risk ranking and dependability assessments can jointly inform the selection of monitoring requirements for catch related risk factors. Data adequacy for other conservation risk factors (habitat and other non-catch related factors) will be determined in a qualitative manner using available expertise.

Given the quantitative nature of the dependability assessments, fisheries science will need input from managers in regards to the acceptable level of risk. Choices regarding risk tolerance are a management decision. Science needs to factor in the acceptable level of risk tolerance with respect to failing to meet the conservation objective. Precisely how to indicate risk tolerance is currently under development.

3.4.3 Compliance objectives

It is important to determine whether the fishery monitoring requirements for the conservation objectives are satisfactory to meet the compliance objectives. For example, the monitoring level and distribution of area coverage may be different. Science and Enforcement must then collectively settle on Departmental priorities for these requirements.

3.4.4 Cost, practicality, and other considerations in setting monitoring requirements

The policy acknowledges as a core principle that the specific monitoring methods and tools used to achieve monitoring objectives must be as practical and cost effective as possible. DFO is committed to working with harvesters and service providers to assess the operational feasibility and affordability of proposed monitoring programs.

Cost effective monitoring could include the use of new technologies such as electronic logbooks and video monitoring systems. It could mean improving the quality of existing data collection systems, coordinating monitoring across multiple fisheries, or adjusting fishing practices to respond to specific risks identified without increasing monitoring at all. These are just some ideas to minimize the direct and indirect costs of monitoring. It is important to note that while cost and practicality are key considerations, ensuring sufficient rigour to achieve the policy and fishery objectives is the ultimate goal of the fisheries monitoring policy.

3.4.5 Documenting rationale for monitoring requirements in IFMP

Box 7: Summary of results to be documented (e.g., in IFMPs)

- The output and rationale from the assessment methodology for data adequacy and estimate dependability,

- The output and rationale from the risk screening tool e.g., the assigned risk categories for each risk factor

- Any newly established fishery specific monitoring objectives

- Adjustments to existing monitoring or additional requirements, and rationale for them

- Specific goals, phases, steps, and timelines to reach the required monitoring levels

The rationale for the monitoring requirements, including coverage levels and the required level of dependability, must be documented by fishery managers in the fishery’s IFMP. This rationalization must include an explanation on how and why the fishery monitoring requirements were determined, including why the required level of dependability of the data estimates was chosen. To this end, we recommend that the six Procedural Steps for fisheries monitoring decision-making in federal fisheries be documented in IFMPs. See Box 7 for details.

The following is an example of a rationale on why certain fishery monitoring requirements might be chosen:

A fishery has 5% at-sea observer coverage. Science has given advice on setting a total allowable catch in a range of 100 to 200 ton. A fishery manager would like to estimate the total retained catch of species X in the fishery. Through the analysis of the current monitoring program, it was found that the quality of the fishery monitoring data currently collected was of low quality and dependability. The fishery manager has two options:

- Continue with the current monitoring program that produces a low quality of data but at the same time, as rationale for allowing this low quality, set the TAC at the lower range value of 100.

- Improve the fishery monitoring program (e.g. raise the ASO coverage level) and allow a higher range TAC of 200 as rationale for the required improvements in the program.

3.5 Develop and operationalize fishery monitoring program (Step 5)

Lead(s): Harvesters with service providers

Support: DFO – FM, DFO - Science, DFO - C&P, others if applicable

Fishery monitoring programs should be implemented through the IFMP process or through other fishery planning processes, such as those used for Indigenous fisheries and recreational fisheries. DFO will use the process described above to determine the monitoring requirements and communicate these to harvesters, e.g., via licence conditions. In many cases, commercial harvesters will design the specifics of the fishery monitoring program in coordination with contracted At-Sea Observer (ASO) and Dockside Monitoring Program (DMP) service providers. This will determine the required fishing monitoring methods, coverage levels, and equipment to be purchased and installed.

Box 8: Self-monitoring by Indigenous and / or community based organizations

The department is open to alternative means of program delivery, including cases where parties wish to conduct their own monitoring and reporting, which may be the position of some indigenous groups. Independent verification is often a consideration, but it is not necessarily required in all fisheries.

An important part of the design of the fishery monitoring program is to ensure that the data infrastructure is in place that allows data users to have easy and secure access to timely, complete, and consistent data of defined quality. The fishery monitoring information must be subject to DFO data standards and formats.

If the proposed program is affordable and implementable, the program can be operationalized. If the program is not deemed affordable or operationally feasible for harvesters or DFO, a modification may be needed. The fisheries monitoring policy states that where a fleet is not willing or not able to pay for a fishery monitoring program in a fishery, all alternatives must be explored, in order to achieve the policy and fishery objectives, including a more conservative management regime.

Regional Work Plans

The policy aims at implementing all approved recommendations as quickly as possible. However, some gaps will take longer to address than others, e.g., due to technical issues or resource availability. Regional Work Plans will be developed to provide concrete actions, timeframes, costs, and responsible leads to ensure gaps are addressed in a timely manner.

Flexible Approach to Implementing the Six Steps

It is important that the longer-duration tasks do not impede progress in implementing the policy. While the six steps outlined above must be followed, it is not necessary that all actions/tasks identified in steps 3 and 4 (setting monitoring objectives and specific requirements) must be implemented to begin step 5 (operationalizing the program). A flexible approach to implementation is envisioned, whereby managers and harvesters can:

- Accelerate tasks where the resources exist and the need is greatest

- Set longer timelines for tasks that need more development or are less critical

3.6 Review the fishery monitoring program against the monitoring objectives and report (Step 6)

Lead(s): DFO - FM

Support: DFO - Science, DFO - C&P, harvesters, others if applicable

Review of policy implementation will take place fishery-by-fishery, and at the national level.

3.6.1 Assessment at the fishery level

Through the post-season review process, DFO will evaluate each fishery unit to see whether its revised fishery monitoring program achieves the stated monitoring objectives. If required, the program will be adjusted and re-launched the following season. The risk screening for each fishery unit may need to be revisited during post-season review to address any needed changes to the risk scores and to consider improved knowledge of risks posed by the fishery.

3.6.2 Assessment at the national level

On an annual basis, DFO will consider batches of fisheries, by region or by species group (e.g., “groundfish”), and assess how well their monitoring programs align with the policy objectives.

Finally, on a multi-year basis, DFO will track progress to implement the fisheries monitoring policy using the Sustainability Survey for Fisheries. This tool will use metrics to report which policy Steps have been implemented. For example, the survey will track whether a review of a fishery’s monitoring program has started, is underway, or is completed, for all assessed fishery units.

- Date modified: