Proposal from the Area-Based Management Technical Working Group to the Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Body

May 22, 2020

On this page

- Executive summary

- Background

- Context

- Definition

- Vision

- Scope

- Guiding principles of ABAM

- Anticipated outcomes of ABAM

- Review of area-based management approaches for fisheries and aquaculture

- Area delineation and scale

- Governance structure

- Tools

- Next steps: Considerations for implementation of ABAM

- Conclusion

- Recommendations

- Sources of information

- Appendix A: Area-based Management Technical Working Group terms of reference

- Appendix B: Delegate/member List

- Appendix C: List of identified assumptions

- Appendix D: Anticipated outcomes

- Appendix E: Summary of area-based management approach review

- Appendix F: Values for area delineation

- Appendix G: Table of tools reviewed

- Appendix H: Accountability table: An assessment of the ABM TWG progress against TOR objectives

- Appendix I: Glossary: Terms and acronyms

Executive summary

In response to growing concerns about the marine finfish aquaculture industry’s environmental impacts, in December of 2018 the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, and Canadian Coast Guard announced that Canada would “work in partnership with the provinces and territories, industry, Indigenous partners, environmental groups and other stakeholders to ensure an economical and environmentally sustainable path forward.” To meet the commitments of December 2018, on June 4, 2019 the Minister announced the creation of an Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Body (IMAB) and three Technical Working Groups (TWGs): (1) Salmonid Alternative Production Technologies; (2) Marine Finfish and Land-based Fish Health and (3) Area-Based Management. These Technical Working Groups were tasked to develop recommendations to improve aquaculture management in British Columbia (BC).

Globally there is an increasing focus and need for food sustainability and security. In BC, significant declines in wild salmon stocks have brought challenges to the culture and socio-economic fabric of First Nations and non-Indigenous communities, elevating the importance of food security and socio-economic well-being for these coastal communities. Aquaculture has the potential to address some of these challenges, but has recently experienced limited growth due to concerns over the regulation and management of the sector.

The report presents the recommendations of the Area-Based Management Technical Working Group (ABM TWG). The ABM TWG undertook discussion focused on transforming the way aquaculture is managed in British Columbia towards an area-based management approach*. Area-based management of aquaculture is anticipated to enable the aquaculture sector to develop in environmentally and socially suitable areas where First Nations and local communities are supportive of the industry, resulting in improved social licence, investor certainty, and environmental management while enhancing food security and sustainability.

The members of the ABM TWG propose the following recommendations, in support of the development of an area-based aquaculture management approach, be approved by the Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Body on Aquaculture and advanced to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard for consideration on how to improve the sustainability of all aquaculture activities (marine, freshwater and land-based) in British Columbia. It is emphasized that the proposed framework is only the beginning and that the body of work to transition to a new management regime is yet to come, including the collaborative identification of a pilot area(s) and roles and responsibilities for governance bodies.

* Terms used in this document may not be consistent with how they are used internationally and within industry, but are defined in Appendix I to ensure clarity and common understanding related to this document and the work of the ABM TWG.

Recommendations

- It is recommended that the area-based aquaculture management (ABAM) framework described in this document is approved.

Key actions would include:- 1.1. The establishment of a regional-level tripartite (Federal, Provincial and Indigenous) BC Area-Based Aquaculture Management Committee (BC ABAMC) to continue to advance the development and adoption of an iterative and responsive area-based approach to aquaculture management.

- 1.2. The BC ABAMC would be established by way of an agreement between the 3 levels of government (Indigenous, Provincial, and Federal) including, but not limited to, the following:

- Recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982;

- Acknowledgement that the ABAM approach is not seeking to determine the existence, nature or scope of Aboriginal or Treaty Rights, but rather is seeking to provide for the orderly management of aquaculture and the direct involvement of the Indigenous Communities in the management of aquaculture;

- The contributing Parties must have interest in the management of aquaculture;

- Confirmation by Parties of their commitment to a relationship based on mutual respect and understanding;

- Commitment from all parties to seek resources to support the development of an ABAM approach.

- 1.3 The BC ABAMC should:

- Identify province-wide management objectives, derived from the outcomes identified in this document.

- Develop an action plan in consultation with industry and stakeholders, which includes specific strategies and actions with timelines and performance measures, to ensure continued progress on the development and implementation of an Area-Based Aquaculture Management (ABAM) Framework including consideration of an area-based pilot or pilots to test and refine the approach.

- Establish an associated “Knowledge Support” body to provide transparent and inclusive advice to address information gaps, and advance the current state of knowledge pertaining to aquaculture and management objectives to inform the implementation of ABAM.

- Establish feedback mechanisms for assessing the effectiveness of management measures and changing such measures as necessary to fit local conditions.

- It is recommended that a nested, integrated and holistic ABAM approach be developed and implemented that respects Indigenous laws and knowledge, Indigenous rights, court direction, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Key actions would include:- 2.1. The development and implementation of a broad and inclusive engagement strategy to share information and increase awareness of the proposed ABAM Framework and seek expressions of interest from Indigenous communities in participating in further development and pilot testing of the proposed ABAM framework.

- It is recommended that the following 4 initial key components be considered when delineating boundaries:

- Consent of the Indigenous Peoples of the area;

- Ecosystem functions and services;

- Presence and operational logistics of existing industry, and potential for development of aquaculture activity(ies);

- Existing administrative boundaries.

- It is recommended that pilot areas be identified through the engagement of Indigenous rights and title holders.

- It is recommended that a minimum of 3 administrative levels be adopted (province-wide level, Aquaculture Management Area, and Site specific), the first two of which would have Governance Bodies, while allowing flexibility to further delineate zones to address local management objectives.

- It is recommended that resources (financial and human) be sought by all parties to pilot test the ABAM framework, and expand further if successful.

- It is recommended that the implementation of an ABAM approach consider the recommendations of the Salmonid Alternate Production Technologies and Marine Finfish and Land-based Fish Health Technical Working Groups.

- It is recommended that a broader and deeper assessment of tools supporting the implementation of area-based approaches be completed to serve as a useful reference for ABAM committees. It is further recommended that all parties use a Province-wide data/information management system as a common tool to integrate and share data and information.

Key Actions would include:- 8.1. Issuing a contract to further identify and evaluate tools supporting the adoption and implementation of area-based management approaches.

- It is recommended that ABAM be considered by DFO and at Parliament during the development of the new federal Aquaculture Act.

Background

The management of aquaculture in BC is a complex effort jointly shared among the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia, Indigenous communities, industry and many stakeholders that have interests in how aquaculture activities interact with BC’s rich and highly diverse marine and freshwater ecosystems. Aquaculture, which includes shellfish, finfish, marine plants, and freshwater sectors, is an economically important industry and employer in BC, generating jobs, often in areas with limited employment opportunities.

Since December 2010, aquaculture activities in BC have been managed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada under the Pacific Aquaculture Regulations and applicable provisions of the Fishery (General) Regulations (FGR) and other federal fishery regulations. Prior to December 2010, these activities were primarily managed by the Province of British Columbia. Currently the Province of BC issues tenures where operations take place in either the marine or freshwater environment, licenses marine plant cultivation, and manages the business aspects of aquaculture such as workplace health and safety.

Aquaculture in BC has operated with varying levels of public support. In 2017, concerns over the industry led the Province of British Columbia to convene an Advisory Committee to develop recommendations to provide strategic advice and policy guidance to the Minister of Agriculture on the future, and issuance of, new Crown land tenures for marine-based salmon aquaculture in BC. This Minister of Agriculture’s Advisory Council on Finfish Aquaculture released a report on January 31, 2018, which included a recommendation to Governments to “adopt a new area-based management approach that considers cumulative risks”.

In further response to concerns about the industry, in October 2018, during the launch of the International Year of the Salmon, the federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, and Canadian Coast Guard announced that the Government of Canada would likewise adopt an area-based approach to aquaculture. Further to this, in December 2018, the Minister announced that “Canada would work in partnership with the provinces and territories, industry, Indigenous partners, environmental groups and other stakeholders to ensure an economical and environmentally sustainable path forward for aquaculture.” This announcement included a commitment to move towards “an area-based approach to aquaculture management – to ensure that environmental, social and economic factors are taken into consideration when identifying potential areas for aquaculture development – including considerations relating to migration pathways for wild salmon.”

To meet the December 2018 commitments, on June 4, 2019 the Minister announced the creation of an Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Body (IMAB) and three Technical Working Groups (Salmonid Alternative Production Technologies, Marine Finfish and Land-Based Fish Health and Area-Based Management), to develop recommendations to improve aquaculture management in British Columbia.

The purpose of the Area Based Management Technical Working Group (ABM TWG) was to investigate and recommend concrete actions for the transition of aquaculture from site by site management to an area-based management approach to enhance the sustainability of aquaculture and support the protection and conservation of wild fish in the Pacific Region. The ABM TWG was guided by defined Principles and established Objectives contained within the Terms of Reference for the group (Appendix A).

The ABM TWG held eight meetings: six in-person meetings, one in Vancouver on August 8, 2019 and five in Nanaimo on September 13, October 10, November 5, December 10, 2019 and January 9 and 10, 2020; and two videoconferences, one on March 18 and 19, 2020 and the last on April 29, 2020 to review the final draft of the Proposed Framework report.

The ABM TWG wish to acknowledge the contributions and expertise of all participants (delegates from the shellfish and finfish aquaculture industries, environmental groups, and local government, ex-officio from the Provincial and Federal Governments) and specifically those of the First Nations delegates who have participated in meetings, with the understanding that the contents and recommendations of this report are not endorsed by the First Nations Fisheries Council or any individual First Nations including the First Nations of whom the participants are members. For a list of delegates see Appendix B.

The following report forms the proposed framework for an Area-Based Aquaculture Management (ABAM) approach in BC and provides details on the objectives, deliberations and recommendations of the ABM TWG for consideration by the IMAB.

Context

A variety of species are cultured in BC including, but not limited to, oysters, scallops, clams, salmon, trout, tilapia, and seaweed. Culture takes place on land, in lakes and ponds and in the marine environment. The current management approach is site-by-site via an application process. A mix of challenges (environmental and social concerns with industry practices, governance, management and cumulative effects) and opportunities (enhance food security, reconciliation, and economic development/employment) are drivers for change.

Food security

Globally, wild fisheries resources are currently at the maximum rate of exploitation or overexploited. Aquaculture is necessary to contribute to food security for a growing world population. As of 2016 aquaculture accounted for 45% of the total global fish production and continues to grow faster than any other food production sector (FAO, 2018).

Regionally significant declines in wild salmon stocks in BC have brought challenges to the culture and socio-economic fabric of First Nations and non-Indigenous communities, elevating issues of food security and economic well-being in importance. For the first time, some First Nations are not able to meet their food, social and ceremonial requirements for their communities. Closures of recreational and commercial fisheries to protect vulnerable salmon stocks have also resulted in significant economic impacts to coastal communities that depend on these industries for their well-being. While closures have occurred in the past, the current stock status and salmon outlook on a coast wide basis continues to be lower than historic averages with uncertainty in terms of harvest opportunities in future years. Chinook salmon, in particular, face unprecedented stock declines across their range. Efforts by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and other government agencies, First Nations, conservation groups and the public are being undertaken, but have not yet reversed these declines.

Food safety, traceability and sustainable practices need to be foundational for the seafood sector in BC. From a food security perspective, aquaculture can help to address global and regional concerns; globally, by providing an important alternative to wild sources of protein, and regionally by taking pressure off wild species (which Indigenous peoples rely upon for Food, Social and Ceremonial purposes) and increasing freshwater survival of wild stocks of coho, chinook and chum salmon through enhancement opportunities. In order for the aquaculture industry to contribute to a sustainable seafood sector there needs to be reliable sources of supply (for example: smolts, fry, spat and juveniles) as well as access to markets.

Reconciliation with First Nations

The Government of Canada is moving forward in setting a new direction and relationship with First Nations by focusing on tangible actions to move towards reconciliation. The Government of Canada has articulated that the relationship with Indigenous Canadians is the most important relationship for the Government of Canada and that a key priority of the mandate of this government will focus on advancing reconciliation. This reconciliation agenda underpins the work of the Area-Based Management model that gives life to advancing this priority by moving in the direction of co-management for aquaculture in British Columbia.

Similarly, the Government of British Columbia has set out clear policy direction that supports a new relationship with First Nations based on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In June of 2018, the province announced that by 2022, all salmon farms will require First Nations approval as a condition tenure. Following this announcement, in December 2018, BC joined the ‘Namgis, Kwikwasut’inux Haxwa’mis and Mamalilikulla First Nations in announcing recommendations for aquaculture in the Broughton Archipelago that would protect and restore wild salmon stocks, facilitate an orderly transition plan for open-pen finfish in that area and create a more sustainable future for local communities and workers. This agreement also facilitated increased First Nations involvement in the management of the industry.

In November 2019, the BC Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act was passed, setting the legal framework to recognize Indigenous peoples’ human rights in BC law and enshrine free, prior and informed consent into decision making.

Environmental and social concerns

Growth of the finfish aquaculture sector in BC has been limited by concerns regarding the potential impacts of the industry on wild fish and fish habitat, cumulative effects, and concerns with adequacy of industry regulations. Differences of view in the science used to identify risks and underpin decision making has been polarizing and contributed to a lack of social licence for the sector, fractured relationships, and lack of trust. Community concerns related to debris from shellfish farms, viewscape, as well as issues related to food safety including traceability has impacted social licence for shellfish aquaculture.

At the same time, changes in ocean conditions and climate change are impacting wild stocks and aquaculture operations. There is limited understanding about how these changes will affect marine and aquatic ecosystems, but impacts have been observed, such as extended periods of waters corrosive to shellfish and increased mortality of species, such as oysters, during the summer months. Similarly in finfish aquaculture, changing oceanographic conditions as a result of climate change can create conditions favorable to harmful algal blooms, increasing their frequency, intensity and duration resulting in mortalities on farms. Investing in climate change resilience and adaptation will be important considerations for the long term sustainability of fisheries and aquaculture in BC.

New technology and diversification

Historically, aquaculture in BC has focused on marine netpen salmon farming, egg and fry production, and culture of oysters and clams. Diversification in the freshwater sector as well as new technologies using different culturing systems holds promise for a wide range of opportunities, including new species. Many First Nations are interested in using culture techniques to enhance salmon stocks in their territories and approaches such as ocean ranching and offshore aquaculture used in other jurisdictions are also of interest in BC. Work completed by the Alternative Production Technologies Working Group may facilitate this diversification, although there are policy and regulatory gaps that will need to be addressed.

The work of the ABM TWG has focused on transforming the way aquaculture is managed in BC towards a more participatory and area-based management approach. It is anticipated that area-based management of aquaculture will result in a number of positive outcomes (see Anticipated Outcomes and associated Appendix) that will support sustainable development and operation of aquaculture in a way that aligns with governmentFootnote 1 priorities.

The adoption of an area based approach can improve the environmental sustainability of aquaculture thus improving social licence, investor certainty, environmental management while enhancing food security and sustainability.

Definition

The TWG has defined Area-Based Aquaculture Management (ABAM) as:

A process where governmentsFootnote 1, communities and industry work together to spatially plan, manage, monitor and continue to improve aquaculture activities at geographical scales that link jurisdictional, ecological, social, cultural and economic systems. It is a practice that aims to support economic viability while maintaining the long term sustainability of aquatic ecosystems and services.

Vision

The TWG discussed the need for a vision that would set a direction or path forward for the group’s work. The vision below was written to be durable and reflective of an aspirational, forward state for aquaculture.

Aquaculture activities are spatially planned and managed at multiple scales as part of interconnected cultural, social and environmental systems through collaborative, integrated, and adaptive processes to achieve sustainability for generations to come.

Scope

The TWG proposed that the scope include, but not be limited to, marine finfish, shellfish, freshwater/land-based (including enhancement) aquaculture, mariculture and ocean ranching, as well as associated activities (such as processing, spat and broodstock collection).

In defining the scope of ABAM, it is necessary to situate it within, and relate it to, other existing planning and management initiatives in BC (see diagram below).

Figure 1 - Text version

This figure is a diagram illustrating how area-based aquaculture management would be situated within existing area-based and spatial planning initiatives in BC. The figure consists of 3 nested circles overlaid on one another to illustrate how area-based aquaculture management would be situated within and related to other existing area-based and spatial planning initiatives in British Columbia. The largest bottom or base circle contains the words “Marine Spatial Planning” followed by parenthesis with the words “Multi-sector Management” and a list with the following acronyms: MPAs (Marine Protected Areas), MaPP (Marine Plan Partnership), PNCIMA (Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area) and Indigenous Marine Plans.

The next mid-sized circle sitting on top of the bottom circle contains the words “Single sector area-based management” followed by parenthesis with the words “Bay Scale Industry Management” and a list including “ABAM” and “Fisheries Management by Area”.

The smallest circle which sits upon the previously described circle is entitled “Site Specific Management” followed by parenthesis which includes the words “farm level”.

Given the nesting of initiatives as well as the involvement of various jurisdictional authorities, implementation of ABAM will require building relationships and linking governance models to ‘knit’ all the pieces together.

Guiding principles of ABAM

The ABM TWG agreed that the ABAM approach must be ecosystem based. Aguilar-Manjarrez et al. (2017). identified three principles of the Ecosystem Approach to Aquaculture. They are:

- “Aquaculture should be developed in the context of ecosystem functions and services (including biodiversity) with no degradation of these beyond their resilience;

- Development of aquaculture should improve human well-being with equity for all relevant stakeholders (e.g. access rights and fair share of income);

- Aquaculture should be developed in the context of other sectors, policies and goals, as appropriate.”

The ABM TWG has developed the following Guiding Principles, upon which the ABAM framework in British Columbia is established:

- Respecting Indigenous rights and title: The ABAM approach respects Indigenous rights, titles and treaty rights, UNDRIP, and reconciliation commitments.

- Knowledge-based: Decisions and recommendations are based on equal consideration of available information from multiple sources (Indigenous, local and scientific) and disciplines (legal, social, economics, biological etc.).

- Ecological integrity: ABAM seeks to sustain biological richness and services provided by natural ecosystems, at all scales through time. Within an ABAM approach, aquaculture related activities will respect biological thresholds and not adversely affect the long term resiliency of ecosystems.

- Sustainable: ABAM will ensure broad-scale and cumulative effects of aquaculture activities are considered for each area to sustain ecological integrity, biodiversity and sustainable use of these ecosystems.

- Resilient to climate change: ABAM will support the ability of communities and the aquaculture sector to better adapt to, and withstand climate change and its impacts on aquatic ecosystems. ABAM will carefully identify, assess, and manage climate-related risks and opportunities. It will aim to respond to climate change forecasting through data harnessing and modelling (technology) and plan for the projected impacts to aquatic ecosystem changes.

- Integrated: ABAM will be integrated with, and linked to other existing planning and management processes, where possible, to avoid overlap and duplication. ABAM recognizes that aquaculture activities occur within the context of nested and interconnected social and ecological systems. It is acknowledged that cumulative impacts of aquaculture will not be considered in isolation; other inputs (natural or anthropogenic) to the system will be considered in tandem.

- Collaborative: ABAM will be a government to governmentFootnote 1 process and include industry and stakeholders. It recognizes the value of shared responsibility and shared accountability. It acknowledges cultural and economic connections of local communities to aquatic ecosystems.

- Accountable: All participants will be accountable for sharing information to the process and providing information back to their communities and/or organizations, and reflecting the views of their organizations and/or communities.

- Transparent: Decisions and recommendations are made openly, with information and results shared with all governmentsFootnote 1 and stakeholders.

- Precautionary: ABAM will err on the side of caution in its management of aquaculture activities when available knowledge is uncertain, and will not use the absence of adequate information as a reason to postpone action or fail to take action to avoid harm to fish stocks or their ecosystems.

- Adaptable: ABAM approach is iterative and responsive. It includes ongoing mechanisms for assessing the effectiveness of management measures and changing such measures as necessary to fit local conditions.

- Human well-being: ABAM approach accounts for social and economic values and drivers and aims to sustain cultures, communities and economies over the long term within the context of healthy ecosystems.

During the conversations which resulted in the formulation of the Definition, Vision and Guiding Principles, members identified a number of assumptions pertaining to the process and aquaculture in BC. These were recorded and can be seen in Appendix C.

Anticipated outcomes of ABAM

In order to develop the outcomes or goals of an ABAM approach, the ABM TWG considered the current state of management and then proactively answered the questions:

- what problems need to be solved; and

- what opportunities are underdeveloped?

In other words, what would be different if we adopt an area-based approach to aquaculture management?”

Anticipated outcomes are summarized below (for additional information/scoping of the Outcomes see Appendix D).

| From | To |

|---|---|

| Site-by-site management | Ecosystem-based planning & management |

| Consultation with First Nations | Nation to Nation collaborative planning & management |

| Western science based | Inclusive knowledge/Multiple ways of seeing |

| Closed decision-making process | Transparent decision-making process |

| Competition with other uses (water and land) | Consideration of other uses (water and land) |

| Fragmented accountability | Shared accountability |

| Food resources at risk | Enhanced food security and sustainability |

| Limited economic benefits for coastal and rural communities from aquaculture | Improved economic benefits for coastal and rural communities from aquaculture |

| Low public confidence | Increased social licence |

Review of area-based management approaches for fisheries and aquaculture

To support analysis and develop a shared understanding of the concept of area-based management, the ABM TWG identified and examined many examples of how area-based management approaches are being applied in other sectors and jurisdictions both within and outside of Canada. The analysis was not exhaustive, rather a selective review of approaches based on the knowledge and suggestions of TWG members. A summary of the approaches can be found in Appendix E.

While the scope of approaches examined was broad, the results of the review revealed a number of common elements to assist in the development of a potential ABAM framework for British Columbia. Key lessons learned included:

- The importance of developing a common vision, goals, objectives and strategies for action with clear accountabilities for achieving results;

- The need to establish transparent and participatory management frameworks involving all levels of government, including Indigenous governments, supported by clear paths for stakeholder and community engagement;

- Recognition that governance and management is a shared responsibility and that all participants are accountable for success and failure;

- The importance of using information from multiple sources and disciplines to support the adoption and ongoing functioning of an area-based approach;

- The key role played by champions and ensuring that all parties respect and support the process and its results;

- The need for adequate resourcing (financial and human) from all partners to enable participation and ensure that key questions can be addressed;

- The adoption and use of a variety of data gathering, analytical, modelling, information sharing and feedback tools;

- The process should be tailored to specific scales and objectives; and

- The utility of zoning and the importance of applying guidance, such as codes of practice, standards (for example Marine Stewardship Council standards) and certifications and farm management plans, to provide clear direction and accountability regarding the use of specific aquatic areas.

Area delineation and scale

Integral to any area-based management approach is the delineation of specific areas for management and with that, consideration needs to be given to scale.

How areas may be delineated for ABAM and the scale at which management objectives should be applied, was a focus of much discussion within the ABM TWG considering the complexity and diversity of values (see Appendix F). Listed below are the key considerations identified by the ABM TWG when delineating spatial areas for ABAM:

- Consent of Indigenous Peoples of the area;

- Ecosystem functions and services;

- Presence and operational logistics of existing industry, and potential for development of aquaculture activity(ies);

- Existing administrative boundaries and land designations.

It is recognized that management of the aquaculture sector is scale dependent. Some issues should be addressed coast-wide while others are better addressed at local scales.

Accordingly, the ABM TWG is recommending the adoption of a nested approach for ABAM comprised of three or four scales, as follows, in descending order:

- Province-wide

- Aquaculture Management Area (AMA) (determined in collaboration with local First Nations)

- Aquaculture Management Zone (AMZ) (eg.Sound/Inlet/Watershed level)

- Site specific (farm level)

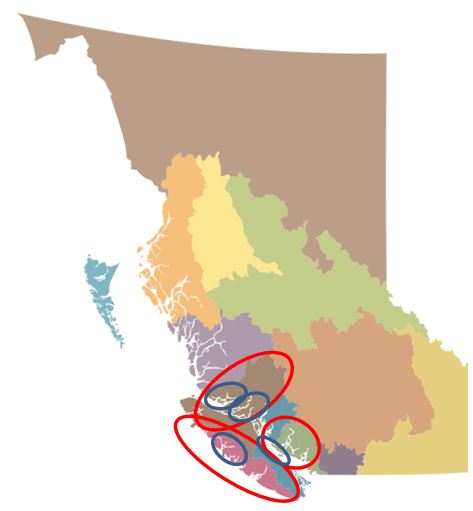

For illustrative purposes only see Figure 2 below (please note that the site specific level was not added due to the scale of the map).

Legend:

Base map represents province-wide area.

Red circles represent an AMA.

Small blue circles represent an AMZ within an AMA.

Figure 2 - Text version

This figure is an illustration of the proposed nested or scaled approach to area-based aquaculture management. The figure is a series of oval shaped rings placed on a base map of British Columbia. The base map comes from the First Nations Fisheries Council (FNFC). The map illustrates 14 different regions of British Columbia, each a different color representing First Nation traditional territories, as defined by the FNFC. This base map is used for illustrative purposes only and does not imply consent of nor endorsement by Indigenous people or groups.

The base map in its entirety represents province-wide management of aquaculture. On the base map are 3 red ovals roughly encompassing three separate geographic areas. These ovals are depicting the next scale of management. The first red oval overlays the west coast of Vancouver Island from Brooks Peninsula down to Sooke, the second oval encompasses Johnstone Strait, the Discovery Island and the associated mainland inlets, and the third oval, the northern Strait of Georgia and associated mainland inlets.

Smaller blue ovals sit within the red ovals. These blue ovals are meant to depict the next layer of management at coastal sound or inlet scale.

The red oval that encompasses the west coast of Vancouver Island contains one blue oval that roughly corresponds with Clayoquot Sound, north to the village of Tahsis.

The red oval that encompasses Johnstone Strait, the Discovery Island and associated mainland inlets contains two blue ovals, the first roughly corresponds with the Broughton group of islands, and the second corresponds with the northern Discovery Islands, including Bute Inlet.

Refinement or definition of Aquaculture Management Areas (AMAS) would occur at the local level with consideration to First Nations’ territories. The proposed boundaries of Aquaculture Management Zones (AMZs) would be ecosystem based and determined through the collective Indigenous and local knowledge and science. The AMZ would be used to designate a management area that defines a biophysical unit that requires co-ordinated management for specific management objectives (ex. Fish health, aquatic invasive species or water quality) identified by the governing body established for that area (for more information see the section Governance Structure below).

Should the size of the AMA be such that it, aligns with a biophysical unit then AMZs may not be required. The biophysical boundaries may not always align with boundaries of an AMA. Where the boundary of one AMZ crosses into another AMA, then the governing bodies of the AMAs will need to collaborate to set and achieve ABAM objectives.

Governance structure

Integral to the adoption of an ABAM approach is the establishment of a supportive governance structure. Based on the identified administrative spatial areas above, the following governance structure is proposed (Figure 3). There are two administrative levels that would require governance bodies: the province-wide level and the Aquaculture Management Area level.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure three is a diagram visually depicting the proposed governance structure described within the associated text. This diagram consists of a number of inter-connected text boxes. Each text box represents a component of the proposed governance structure. At the top of the diagram there is a blue oval with the words “BC Area-based Aquaculture Management Committee” in it. Following these words are parenthesis containing the words “Federal, Provincial and First Nations” which are separated by back slashes.

There is a double headed arrow from the overarching blue oval to a large text box in the middle of the figure below. This box contains the next two layers of governance: the Aquaculture Area-based Management Committees comprised of Indigenous, Federal, Provincial and local governments (written within and along the left side of the box), and the optional Aquaculture Management Zones on the right.

The lower geographic scale committees are is illustrated through example by three Aquaculture Management Areas depicted by three different colored ovals entitles Area A, Area B and Area C. These three ovals are oriented vertically within the large central text box.

The Area A oval is connected to the Area B oval via a double headed arrow. The Area B oval is connected to the Area C oval via a double headed arrow.

The Area A oval has 2 double headed arrows extending from the right. Each arrow connects to a rectangle containing the abbreviation AMZ, which stands for Aquaculture Management Zone. The upper rectangle has the number 1 following the abbreviation of AMZ and the lower rectangle has the number 2 following the abbreviation AMZ. The rectangles are stacked one above the other.

The Area B oval has one double headed arrow extending from the right. The arrow connects to a rectangle containing the abbreviation AMZ 1.

The Area C oval has two double headed arrows extending to the right. Each arrow connects to a rectangle containing AMZ 1 and 2 respectively. The rectangles are stacked one above the other.

Immediately below the five stacked rectangles containing “AMZ” is a bracket below them indicating that “Aquaculture Zones may be established”.

Running vertically, to the left of the main center box is a long bracket. The bracket extends upward to include the initial blue oval containing the words “BC Area-based Aquaculture Management Committee” and down the full length of the central box. The bracket connects these to another oval containing the words “ABAM Secretariat” and included a parenthesis containing the words “DFO or alternate”.

Running vertically, to the right of the main governance box in the center is another long bracket. The bracket only encompasses only the center box. The bracket connects it to another oval containing the words “Knowledge Support”. This oval has 3 double headed arrows extending from its right which are connected to three boxes that are arranged vertically. The upper box contains the words “Indigenous knowledge and Science”, the middle box contains the words “Government and Academic Science” and the lower box contains the words “Industry and Stakeholder knowledge and Science”.

Below the center governance box is a bracket connecting it to a rectangle that contains the words “Stakeholder and Industry operational input”.

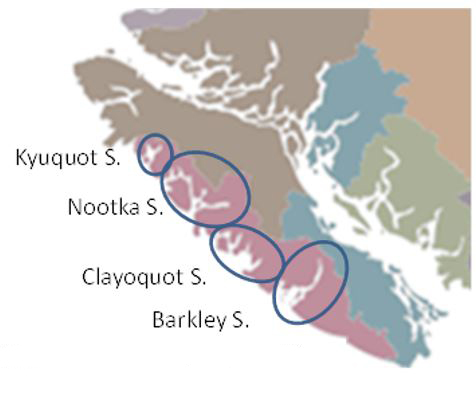

The proposed tiered governance structure includes a BC Area-Based Aquaculture Management Committee (BC ABAMC) that is supported by a Secretariat. The tripartite (Federal, Provincial and Indigenous) BC ABAMC will provide overall guidance for the implementation of the ABAM initiative including development of a work plan with clear timelines and deliverables as well as overseeing the AMAs. It would set regional-level goals, objectives, targets and policies. The BC ABAMC would develop an engagement plan that would include soliciting Indigenous communities for interest in establishing a pilot area (for example see Figure 4). The BC ABAMC will be responsible for evaluating the success of the pilot(s) in order to develop guidance for broader implementation across BC.

For illustrative purposes only, the pink area on Figure 4 represents the hypothetical West Coast Vancouver Island Aquaculture Management Area (WCVI AMA) which would have an associated governance committee. The blue circles would be sound level aquaculture management zones that may or may not have an associated governance body. The WCVI AMA committee would report upward to the province-wide BC ABAMC.

Figure 4 - Text version

Figure four is an illustrative example of what a pilot area might look like. The figure is a black box with text on the left and a map of Vancouver Island with 4 blue ovals on the right.

The text states “For illustrative purposes only, the pink area on the map represents a hypothetical West Coast Vancouver Island Aquaculture Management Area (WCVI AMA) which would have an associated governance committee. The blue ovals represent sound-level aquaculture management zones that may or may not have associated governance bodies. The WCVI AMA committee would report upward to the province-wide BC ABAMC.”

The map uses the First Nations Fisheries Council base map and is zoomed in to view Vancouver Island and the associated mainland inlets. Vancouver Island has three different colors on it that represent First Nation territories as described by the First Nations Fisheries Council. The northern tip of Vancouver Island is shaded light brown and extends down the west coast to just south of Brooks Peninsula and down to approximately mid-way between Campbell River and Courtenay on the east coast. The remainder of the west coast of Vancouver is depicted in pink and extends from the northern region down to Sooke. The south eastern region of Vancouver Island is depicted in blue.

The pink area has four varying sized ovals overlaying Kyuquot Sound, Nootka Sound, Clayoquot Sound and Barklay Sound. The sounds are labelled with their respective names.

The Aquaculture Management Area committees (AMAs) would lead the development of Aquaculture Management Plans and identify any AMZs that need to be established at the sound, Inlet or watershed level. Aquaculture management zones may be utilized as a tool by the AMAs and the need for a governance body associated with the AMZ would be determined by the committee established at the AMA level. Roles and responsibilities of the various levels of governance will be integrated with, and supportive of, one another.

The Secretariat will provide the organizational and logistical capacity to support committees’ conducting their business in the most efficient way and this may include coordination for the process, communications, and regional data and financial management.

The Knowledge Support body will serve in an advisory capacity to provide the BC ABAMC and the AMAs with transparent information from diverse perspectives to inform decisions regarding ABAM.

Stakeholders will contribute information to the various levels of governance. The governing bodies (AMAs or BC ABAMC) will work with stakeholders to define the mechanism and process for engagement at each respective level.

A stand-alone dispute resolution body was not proposed as it is recognized that dispute resolution will happen at the levels at which the dispute occurs with the processes that are developed at that level. Disputes that are not resolvable would be elevated to the next level within the hierarchy of governance.

Integral to the successful implementation of an area based aquaculture management approach is an established feedback mechanism to allow for timely adaptive management to occur.

The ABM TWG undertook preliminary discussions into roles and responsibilities, however next steps in the development of the Framework would include collaborative identification of roles and responsibilities of the governance structures including the BC ABAMC, the AMAs, ABAM Secretariat and Knowledge Support Body.

Tools

The objectives of the ABM TWG Terms of Reference included a review of tools to support ABAM.

The ABM TWG considered the definition found on the European Aquaspace website.

Tool’ means any legal instrument (laws, regulations, guidelines), process (such as stakeholder engagement), computer model application (such as GIS, or computer models to assess impacts of aquaculture), or any other hardware, software or set of instructions that can be used to help and support...

Based on this definition and on the experience of the TWG members, a select number of tools were reviewed which fell within the following categories:

- Legal instruments (laws (Indigenous, local, provincial and federal), regulations, framework agreements etc.)

- Non-legal/quasi-legal instruments (guidelines, Codes of Practice, standards (e.g. MSC), certifications (e.g. ASC) etc.)

- Planning

- Predictive models

- Data/Info. management and sharing

- Communications

- Oceanographic

- Socio-economic and cultural analysis

- Decision making

- Ecosystem services

Given the wide range of tools potentially available to support the adoption of an area-based approach, the TWG determined that only a selective review could be completed at this time (see Appendix G for a table of the tools reviewed). While the use of legal instruments, such as framework agreements between parties, and non-legal instruments, such as guidelines and codes of practice, were identified as tools during the review of other domestic and international examples of area-based management, time did not permit their further examination.

While only a selective review could be completed, the presentations and analysis did clearly identify the need for the use of tools capable of gathering, analyzing and sharing large volumes of geospatial data, such as hydrodynamic models and geographic information systems (GIS), as well as the usefulness of tools that can be used to support collaborative decision making regarding the use and management of aquatic spaces. The presentations by TWG members also clearly illustrated the importance of collectively using tools to support transparency and information sharing amongst all partners. Finally, it was recognized that as the development and maintenance of tools is generally expensive, ABAM processes should try to make use of and build on previously existing tools, where possible.

The use of a variety of tools has been identified as a fundamental and sometimes costly element of adopting an area-based approach. Should a decision be taken to advance ABAM further, it is recommended that a professional services contract or similar effort be undertaken to further gather and analyze details on potential tools that could be used to support the adoption of ABAM in BC.

Next steps: Considerations for implementation of ABAM

The TWG defined the scope of their work as developing a framework for ABAM versus the specifics of ABAM in a particular location. This is the lens through which the following components for ABAM implementation were developed.

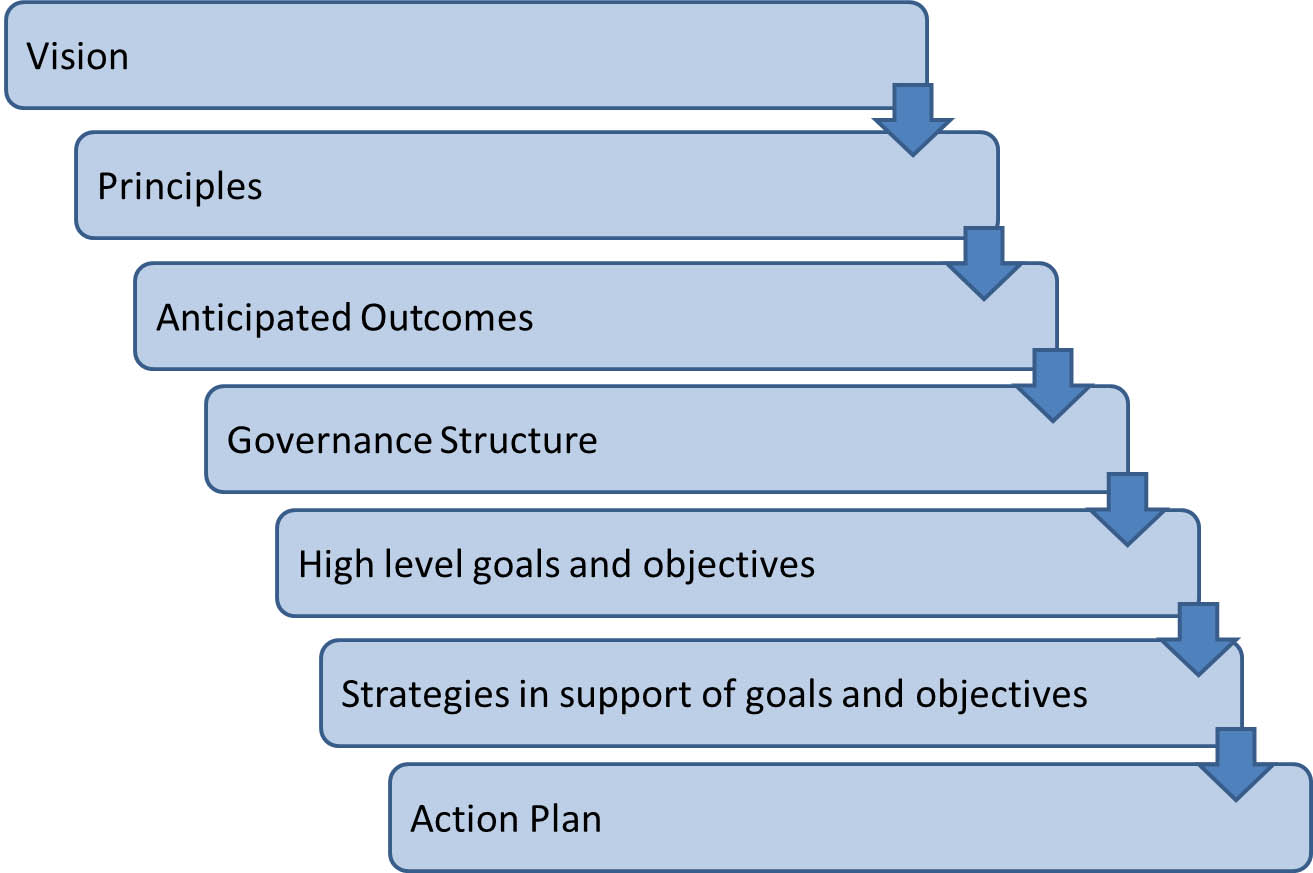

As the scope of the ABM TWG was to develop/recommend a Framework for ABAM in BC, Regional level management goals and objectives would flow from the Intended Outcomes above. These along with subsequent and more specific, Aquaculture Management Area (AMA) objectives will need to be developed and will support or contribute to the success of the higher level objective. Strategies will support the goals and may influence more than one objective as the Figure 5 below suggests.

Figure 5 - Text version

Figure 5 is a stepped flow chart illustrating the steps in the development of an ABAM approach in British Columbia. It has seven cascading steps in that are connected at the right end of each step by a down arrow.

In subsequent order, the steps contain the words: “Vision”, “Principles”, “Anticipated Outcomes”, “Governance Structure”, “High Level Goals and Objectives”, “Strategies in Support of Goals and Objectives” and finally, “Action Plan”.

The framework outlined above should lead to an Action Plan for implementation of ABAM. The Action Plan will include responsible parties and timelines with measurable targets.

Through the review of examples of other area-based approaches and associated conversations, that included the identification of strengths and enabling factors, a number of key considerations were also acknowledged as being potentially useful in supporting successful implementation of an ABAM approach. Some of these conditions for successful implementation include:

- The process for implementation needs to be adequately funded.

- Strong local and/or Indigenous support and/or leadership;

- Early and continued focus on relationship building during processes;

- Clarity on roles and responsibilities of governance structures;

- Use of framework agreements to bring parties together;

- Ongoing and administrative support;

- Adoption of scale-appropriate decision making;

- Transparent decision-making to elicit trust; and

- Utilization of existing structures and processes, where appropriate.

Next steps will need to include the collaborative identification of a pilot area(s) and roles and responsibilities for governance bodies as well as the development of supporting processes (such as dispute resolution) and an engagement strategy.

Conclusion

The ABM TWG has achieved the objectives set out in the Terms of Reference (see Appendix H for Accountability Table) through the constructive and respectful engagement of its diverse membership. Given the limited time to accomplish the terms of reference, the ABM TWG has made choices about where best to place their efforts and where to provide ideas for future work and investigation. The results of this work are presented in this document setting out the proposed framework to develop an ABAM approach for BC. Below are the strategic recommendations and associated actions agreed to and put forward by the ABM TWG:

Recommendations

This document forms the Framework for ABAM in BC and it should be considered in its entirety as all aspect are interrelated.

The members of the ABM TWG propose the following recommendations be approved by the Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group and advance them for Minister approval in support of development and implementation for the purpose of enhanced sustainability of aquaculture. Associated actions are identified where applicable.

ABM TWG proposed recommendations

- It is recommended that the area-based aquaculture management (ABAM) framework described in this document is approved.

Key actions would include:- 1.1. The establishment of a regional-level tripartite (Federal, Provincial and Indigenous) BC Area-Based Aquaculture Management Committee (BC ABAMC) to continue to advance the development and adoption of an iterative and responsive area-based approach to aquaculture management.

- 1.2. The BC ABAMC would be established by way of an agreement between the 3 levels of government (Indigenous, Provincial, and Federal) including, but not limited to, the following:

- Recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982;

- Acknowledgement that the ABAM approach is not seeking to determine the existence, nature or scope of Aboriginal or Treaty Rights, but rather is seeking to provide for the orderly management of aquaculture and the direct involvement of the Indigenous Communities in the management of aquaculture;

- The contributing Parties must have interested in the management of aquaculture;

- Confirmation by Parties of their commitment to a relationship based on mutual respect and understanding;

- Commitment from all parties to seek resources to support the development of an ABAM approach.

- 1.3 The BC ABAMC should:

- Identify province-wide management objectives, derived from the outcomes identified in this document.

- Develop an action plan in consultation with industry and stakeholders, which includes specific strategies and actions with timelines and performance measures, to ensure continued progress on the development and implementation of an Area-Based Aquaculture Management (ABAM) Framework including consideration of an area-based pilot or pilots to test and refine the approach.

- Establish an associated “Knowledge Support” body to provide transparent and inclusive advice to address information gaps, and advance the current state of knowledge pertaining to aquaculture and management objectives to inform the implementation of ABAM.

- Establish feedback mechanisms for assessing the effectiveness of management measures and changing such measures as necessary to fit local conditions.

- It is recommended that a nested, integrated and holistic ABAM approach be developed and implemented that respects Indigenous laws and knowledge, Indigenous rights, court direction, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Key actions would include:- 2.1 The development and implementation of a broad and inclusive engagement strategy to share information and increase awareness of the proposed ABAM Framework and seek expressions of interest from Indigenous communities in participating in further development and pilot testing of the proposed ABAM framework.

- It is recommended that the following 4 initial key components be considered when delineating boundaries:

- Consent of the Indigenous Peoples of the area;

- Ecosystem functions and services;

- Presence and operational logistics of existing industry, and potential for development of aquaculture activity(ies);

- Existing administrative boundaries.

- It is recommended that pilot areas be identified through the engagement of Indigenous rights and title holders.

- It is recommended that a minimum of 3 administrative levels be adopted (province- wide level, Aquaculture Management Area, and Site specific), the first two of which would have Governance Bodies, while allowing flexibility to further delineate zones to address local management objectives.

- It is recommended that resources (financial and human) be sought by all parties to pilot test the ABAM framework, and expand further if successful.

- It is recommended that the implementation of an ABAM approach consider the recommendations of the Salmonid Alternate Production Technologies and Marine Finfish and Land-based Fish Health Technical Working Groups.

- It is recommended that a broader and deeper assessment of tools supporting the implementation of area-based approaches be completed to serve as a useful reference for ABAM committees. It is further recommended that all parties use a Province-wide data/information management system as a common tool to integrate and share data and information.

Key Actions would include:- 8.1. Issuing a contract to further identify and evaluate tools supporting the adoption and implementation of area-based management approaches.

- It is recommended that ABAM be considered by DFO and Parliament during the development of the new federal Aquaculture Act.

Sources of information

- Aguilar-Manjarrez, J, D. Soto, and R. Brummett. 2017. Aquaculture zoning, site selection and area management under the ecosystem approach to aquaculture: A handbook. FOA.

- FAO. 2018. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 - Meeting the sustainable development goals. Rome.

- MAACFA Final Report and Recommendations. 2018. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Rome Declaration on World Food Security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 13 November 1996. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- Rome Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 16-18 November 2009. Accessed March 24, 2020.

Appendix A: Area-based Management Technical Working Group terms of reference

Background and Purpose

The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) announced on June 4, 2019, a series of measures related to the transformation of aquaculture management.

This document outlines the proposed structure and function of focused Area-Based Management Technical Working Group (TWG) to support the development of new and transformative approaches to the management of aquaculture in the Pacific Region.

Guiding Principles

The TWG serves the objective of delivering concrete proposals for actions, guided by the following principles:

- Recommendations are developed and assessed using the best available science and evidence.

- Discussions are informed by a range of policy and technical/scientific expertise in the relevant areas under consideration.

- Recommendations are developed and assessed based on their potential effectiveness in improving the management of aquaculture, recognizing that management can and should adapt over time.

- TWGs will work in a spirit of collaboration and consensus, but will not be required to reach full consensus around any particular proposal.

Objectives

The main objectives of the Working Group will be to:

- Conduct review which highlights the following:

- Review relevant examples of approaches to Area-Based Management in a fisheries and aquaculture context.

- Review the use of various geographic scales as a management tool and assess their appropriate role in an Area-based Management of Aquaculture approach.

- Review information management technologies used in other related initiatives (like conservation planning, GIS analysis).

- Develop a recommendation for a shared definition/vision for Area-Based Management of Aquaculture within Pacific Region.

- Supported by the above, recommend the use of appropriate scale/models for application in an area-based aquaculture management approach in the Pacific Region (linkages to governance and engagement; planning; assessment of applications; management, monitoring, and science/research).

- Recommend any appropriate technology or approaches which could support the above.

Timeframes

The TWG will identify and propose actions that are both short and longer term. The proposed timeframe is as follows:

August Meeting:

- Committee introductions;

- Review and respond to draft Terms of Reference;

- Logistics and organization which includes: respond to proposed tasks and time frame, allocate any tasks, discussion of topics/categories for final recommendations, identification of additional questions/expertise/analysis required, initial identification of any potential interim recommendations which would require work prior to September meeting.

- Plan for the completion of a review which highlights the following:

- Review relevant examples of approaches to Area-Based Management in a fisheries and aquaculture context.

- Review the use of various geographic scales as a management tool and assess their appropriate role in an Area-Based Management of Aquaculture approach.

- Review information management technologies used in other related initiatives (like conservation planning, GIS analysis).

September Meeting:

- Review and discuss background materials and discuss approaches for recommendations.

October Meeting:

- Develop a recommendation for a shared definition/vision for Area-Based Management of Aquaculture within Pacific Region.

- Supported by the above, recommend the use of appropriate scale/models for application in an Area-Based aquaculture management approach in the Pacific Region (linkages to governance and engagement; planning; assessment of applications; management, monitoring, and science/research).

- Recommend any appropriate technology or approaches which could support the above.

November Meeting:

- Finalize recommendations.

Governance and Membership

The TWG will consist of delegates from various Indigenous and stakeholder groups: Indigenous communities, environmental organizations, the aquaculture industry sectors (marine finfish, shellfish, and freshwater/land-based), the Union of BC Municipalities, academia and the Government of British Columbia.

The TWG will be chaired by a senior official from DFO, with ex-officio participation of senior federal officials. The TWG secretariat will report to the Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Body (IMAB), chaired by the Deputy Minister of DFO, on the discussions that were held and the recommendations made, noting the degree of support or divergence among members for advice on different issues.

Additional observers are welcome to listen to discussions; however, participation is limited to members.

Responsibilities of Participants

Review circulated information.

Participate in meetings or assign alternate to attend - once per month until the end of November 2019.

Engage in open and respectful dialogue, seeking to understand and be understood.

Communicate out to their respective organizations/communities the activities and outcomes of this TWG.

Meeting Process

The TWG is anticipated to meet once per month until the end of November 2019; however, this may be adjusted by the Chair, if needed. The meetings will be held in Vancouver, BC. Teleconferencing and video conferencing will be used where possible to minimize travel demands. DFO will provide secretariat services to support meeting delivery and the preparation of summary meeting notes. TWG participants will be invited to propose topics for meetings. Agendas will be approved by the Chair.

Reporting

The Chair will disseminate meeting summary notes through the federal secretariat to this TWG.

Individual participants of this TWG will also report back to their respective organizations.

The Chair/Secretariat will provide draft meeting summary notes that include a record of recommendations and follow-up actions to all participants within two weeks of the meeting. The TWG will have 2 weeks to review summary notes prior to their finalization. The Chair will then provide the final meeting summary notes to IMAB.

Budget and Financial Matters

Direct meeting costs (meeting rooms and videoconference/teleconference technical-related fees) will be covered by DFO.

Each participant will be responsible for their relevant costs associated with participation in the TWG meetings, including travel and accommodations.

Appendix B: Delegate/member List

| Name | Alternate | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel Arbour | - | AVICC / Union of BC Municipalities |

| JP Hastey | - | BC Shellfish Growers Association |

| Shelley Jepps, Secretariat | - | DFO, Pacific, Aquaculture Management |

| Tawney Lem | - | West Coast Aquatic |

| Karen Leslie | Sheila Creighton | DFO, Pacific, Oceans |

| Lesley MacDougall | Jon Chamberlain | DFO, Pacific, Science, Ecosystems and Oceans Science |

| Dr. Craig Orr | - | Watershed Watch Salmon Society, Pacific Marine Conservation Caucus, Simon Fraser University |

| Tony Roberts Jr | - | Campbell River Indian Band, Wei Wai Kum First Nation |

| Linda Sams | Janice Valant | Cermaq Canada |

| Don Simpson | - | Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance |

| Karen Topelko | - | BC Ministry of Forest Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development |

| Allison Webb, Chair | - | DFO, Pacific, Aquaculture Management |

| Darren Williams | - | DFO, NHQ, Aquaculture Management Directorate |

| Karen Wristen | - | Living Oceans |

Appendix C: List of identified assumptions

The list below is an unedited list of the assumptions identified by various members of the ABM TWG:

- ABAM is based upon a solid understanding of the ecosystem and its functions within the defined area and that ecosystems are hydrologically interconnected and exist on multiple spatial and temporal scales.

- The framework for ABAM will be evergreen.

- Marine ecosystems are dynamic and thus human activities within the ecosystem must be provided flexibility to adapt to the changes that occur.

- Biodiversity is critical to ensuring resiliency of ecosystems.

- Ecosystems have limited capacity to absorb and recover from impacts.

- Human knowledge of cumulative impacts is limited.

- There will be a technologically diverse aquaculture industry in British Columbia well into the future.

- There will continue to be regulations applied to the aquaculture industry in British Columbia and the management of the industry will be more effective and efficiently managed with the implementation of ABAM.

- Trust in the process to lead to solutions that result in change.

- ABAM in British Columbia will be the leading example for other marine industries.

- ABAM will be appropriately funded for successful implementation.

- Information and knowledge contributing to ABAM will be evaluated through a defined process prior to consideration in decision making.

Appendix D: Anticipated outcomes

| From | To |

|---|---|

| Site-by-site management | Ecosystem-based planning & proactive management |

| Improved spatial arrangement and site selection of aquaculture will lead to better environmental, social, cultural and shared economic benefits and outcomes, greater public confidence in the sustainability of aquaculture, and improved resilience to climatic variability. ABAM can also provide the ability for threats and cumulative impacts to be better considered and addressed at ecosystem relevant scales, improving results for wild and farmed fish. | |

| Consultation with First Nations | Nation to Nation collaborative planning & management |

| Collaborative approaches to governance and management of aquaculture can support Indigenous self-determination, invite meaningful Indigenous participation in the economy, provide for revenue sharing opportunities, improve accountability, advance reconciliation, provide leadership opportunities for Indigenous peoples and strengthen governance capacity of First Nations. | |

| Western science based | Inclusive knowledge/Multiple ways of seeing |

| The framework for ABAM will ensure that decisions are informed by science (social and biological) and Indigenous knowledge and wisdom. Consideration and respect for multiple sources of information and perspectives will lead to increased understanding of other’s values and ecological impacts at various spatial scales, resulting in better outcomes for governments, communities and stakeholders. | |

| Closed decision-making process | Transparent decision-making process |

| The framework for ABAM will provide for the development of governance structures and processes that support transparent decision-making while respecting the confidentiality requirements of participants. (Transparent meaning visible in its data, governance, science and decision making, with an understanding that some traditional ecological knowledge may not be made public.) | |

| Competition with other uses (water and land) | Consideration of other uses (water and land) |

| An aquaculture industry that is developed and managed in the context of other sectors, policies and goals can help to minimize conflicts and maximize complimentary uses of land and water. Strategic planning allows for the consideration of social, economic, environmental and governance objectives. | |

| Fragmented accountability | Shared accountability |

| Shared accountability comes from joint ownership of decisions which is a product of an inclusive process that allows for relationship building, trust, and transparent decision making. | |

| Food resources at risk | Enhanced food security and sustainability |

| In today’s environment of uncertainty pertaining to food security and sustainability, and given climate change effects on aquatic systems; ABAM can help to minimize risk of disease (to wild and farmed species), address environmental issues (e.g., eutrophication, biodiversity and ecosystem service losses), improved productivity and yield, provide greater quality assurance and certainty for source through targeted development, enhanced traceability and adaptive, coordinated, and responsive management. | |

| Limited economic benefits for coastal and rural communities from aquaculture | Improved economic benefits for coastal and rural communities from aquaculture |

| ABAM can focus development of aquaculture and spin off industries in areas where economic injection is needed and wanted. The identification of aquaculture zones and management areas supported by governments, First Nations, stakeholders and the public will provide industry with the certainty and confidence needed to invest. Communities will benefit from the creation of stable jobs and career opportunities for people with diverse backgrounds, skills, knowledge and training. Strategic planning will also support the identification of areas where the federal, provincial, local and First Nations governments can work together with communities to identify public infrastructure requirements to support industry investment. | |

| Low public confidence | Increased social licence |

| Undertaking ABAM in an open, transparent, inclusive fashion will allow shared governing bodies to engage with communities and the wider public to address issues of environmental, human health and social concern. | |

Appendix E: Summary of area-based management approach review

The Terms of Reference for the Area-Based Management Technical Working Group (ABM TWG) identified the following objective:

- Review relevant examples of approaches to Area-Based management in a fisheries and aquaculture context.

The ABM TWG identified a number of area-based management approaches, shared information on these approaches and reviewed the approaches during the course of several meetings. A summary of the reviewed approaches is provided below:

| Country/Approach | Strengths/Enabling factors | Considerations/Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|

| Beaufort Sea Integrated Management |

|

|

| Bras d’Or Lakes Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative |

|

|

| New Brunswick Bay Management Approach | Shellfish (water column oyster culture)

|

Shellfish

|

| Chile |

|

|

| Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP) |

|

|

| Norway |

|

|

| Scotland |

|

|

| Iceland |

|

|

| Tasmania |

|

|

| West Coast Vancouver Island Salmon Roundtables |

|

|

Beaufort Sea integrated management

The Beaufort Sea Large Ocean Management Area covers over 1 million square km in the extreme northwest of Canada. The basis for the Beaufort Sea Integrated Ocean Management planning process was the growth of the oil and gas industry and the desire by Indigenous people for co-management. Ecosystem health was foundational to the development of this approach.

Source: Integrated Ocean Management Plan for the Beaufort Sea: 2000 and Beyond.

A regional governance partnership was created, which included Indigenous (Inuvialuit), federal and territorial representatives. A regional coordinating committee (RCC) oversees the process and is co-chaired by the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC), the Inuvialuit Game Council (IGC), and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) with representatives from federal regulators, territorial governments and Inuvialuit organizations. Technical working groups addressing identified goals and action plan deliverables report to the RCC and a broad multi-sectoral advisory group, with members from industry, academia, NGOs and others.

The structure of the partnership was set up in such a way that decision making would be transparent. The Inuvialuit Final Agreement and powers provided under the federal Oceans Act provides a framework for a collaborative and transparent process.

The ABM TWG identified the following strengths associated with this approach:

- Establishment of a tri-lateral government framework.

- Established land claims agreement.

Further to the lessons learned, the ABM TWG flagged the following lessons learned:

- Clearly defined roles and responsibilities embedded within a defined management and decision making structure.

- Development and adoption of an action plan with clear goals, objectives, strategies and roles and responsibilities.

- Accountability is necessary and can be established via a reporting back requirement on the Action Plan.

Reference:

Integrated Ocean Management Plan for the Beaufort Sea: 2000 and Beyond.

Bras d’Or Lakes

The Bras d’Ors Lakes Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative (CEPI) arose to develop a management plan for activities occurring within the Bras d’Or lakes and watershed lands. The goal of the CEPI process is to balance environmental, social, cultural and institutional objectives to ensure the health and sustainable use of the Bras d’Or lakes ecosystem.

Source: The Bras d'Or Lakes Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative)

CEPI is led by the 5 Mi’maq Chiefs with support from county, provincial and federal government levels. A Council of Elders and Youth provides advice to the Senior Council, as does a steering committee of government, academia, industry and NGO representatives. Signatories to the charter have clear jurisdiction for the geographic area of their designated lands and responsibilities given through the relevant statutes and laws enacted by various levels of government. To date, the process has developed a series of guiding documents including: an overview and assessment of the planning area, an environmental management plan, Development Standards Handbook, Guidelines and Report and Stewardship Booklet to guide activities within the management area.

The ABM TWG identified the following strengths associated with the CEPI approach:

- Shared accountability of governance partners codified by a Charter.

- Involvement of regional/county government.

- Indigenous-led process and Secretariat.

Key take-away lessons included:

- Initiative was driven by Champions and supported by an Indigenous-led Secretariat.

- It is important that the process be well financed.

- Try to secure consistent leadership through the duration of the planning initiative.

The presenter cautioned that the loss of the champions can destabilize the functionality and progress of the process.

Reference:

Chile

It should be noted at the outset that the development of this management system followed the development of aquaculture, rather than preceding it. In the industry’s initial development, from 1980 until the early 1990’s, growth outpaced the nation’s ability to regulate and the result was poor all around: repeated disease outbreaks, including one in 2007 that severely impacted the industry nation-wide; dissatisfaction in communities and among environmental groups; and poor market perception. The system described below was brought in in phases to respond to this situation.

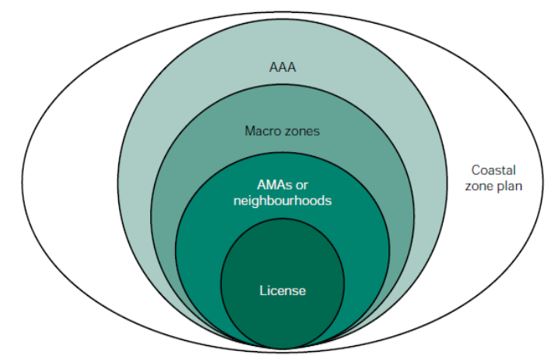

Appropriate Areas for Aquaculture (AAA) were established within the Coastal Zone Plan, created under the General Law on Fisheries and Aquaculture. Each AAA contains macro zones of Aquaculture Management Areas whose purpose is to control the spread of disease in emergency situations. Aquaculture Management Areas (AMA) designed based on a variety of factors that justify their co-ordination (safety, oceanography, epidemiology, geography and operational issues are specifically mentioned). Management of disease, stocking density, fallowing, monitoring and reporting are dealt with at this level.

Figure Appendix E - Chile - Text version

The diagram illustrates the spatial categories of sea cage salmon farming in Chile. Aquaculture Management Areas (AMas) are established for the three species farmed and licenses for individualized species.

The diagram consists of 5 nested circles. Starting from the largest and lowest circle, and in ascending order are the following words and/or abbreviations: Coastal zone plan, AAA, Macro zones, AMAs or neighbourhoods, and finally License on top.

The ABM TWG identified several strengths to this approach:

- Good compliance and certainty;

- Scalable; and

- Included all sectors of aquaculture (including ocean ranching).

The ABM TWG all highlighted several components missing from this approach that were deemed best practices by Aquaculture Stewardship Council:

- tracking the use of antibiotics classified ‘highly important’ by the WHO;

- tracking cumulative use of parasiticides; and

- monitoring antimicrobial resistance.

The ABM TWG also noted that this approach led to increased treatments for lice and provided no opportunities for other interests to be considered.

Reference:

Arriagada, G, Stryhn, H, Sanchez, J, Vanderstichel, R, Campisto, J.L, Rees, E.E, Ibarra, R & StHilaire, S (2017). Evaluating the effect of synchronized sea lice treatments in Chile, Preventative Veterinary Medicine, vol. 136, pp. 1-10.

Marine Plan Partnership (MaPP)

In 2011, the Province of British Columbia and 17 First Nations formally agreed to co-lead development of 4 marine plans and a regional action framework for the Northern Shelf Bioregion. Governance structures established at executive, technical and administrative levels included provincial and First Nations representatives. Decisions were based on consensus, with dispute resolution processes clearly outlined in terms of reference. A science coordinator provided neutral science advice; technical coordinators hired for each sub-region provided capacity to provincial and First Nations planning teams. The planning process was funded by philanthropic organizations, with both First Nations and the Province providing significant in kind support.

The following were highlighted as strengths of the process:

- Indigenous co-development and delivery.

- Use of an independent science advisor.

- Traditional ecological knowledge was considered to be on par with western science which gave a balance of power.

- Spatial management direction is easier to evaluate in terms of performance than a-spatial management direction.

Enabling conditions were also highlighted and included: