Archived – National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative: Overarching Document

2011 - 2015

On this page

Introduction

Canada’s history is one of a rich and enduring set of relationships between its people and its diverse bounty of natural resources. Since long before Canada was established as a nation, aboriginal societies from coast to coast to coast were stewards of the forests, wildlife and fisheries of what is known today as Canada. Europeans were first drawn to North American shores in pursuit of fish, furs and forests, and they established societies and settlement patterns based largely on access to these resources. In many ways, it is no exaggeration to say that modern-day Canada is fundamentally based upon these resource use patterns established so long ago.

Indeed, the harvesting of fish has stimulated the establishment of almost all coastal communities in Canada as well as a myriad of rural towns in the interior of the country, and still powers many of these local economies today.

Our use of our country’s aquatic resources has continued to evolve over time as resource use capacities, market pressures and opportunities, technologies, and societal needs have changed. A key element in this process has been the emergence in recent decades of aquaculture: the farming of fish, molluscs and aquatic plants. Once viewed as a small-scale, localized, low-technology use of marine or freshwater resources, aquaculture has emerged as a substantial national industry in its own right that now generates over a billion dollars in sales annually and employs more than 15,700 people.

Our use of our country’s aquatic resources has continued to evolve over time as resource use capacities, market pressures and opportunities, technologies, and societal needs have changed. A key element in this process has been the emergence in recent decades of aquaculture: the farming of fish, molluscs and aquatic plants. Once viewed as a small-scale, localized, low-technology use of marine or freshwater resources, aquaculture has emerged as a substantial national industry in its own right that now generates over a billion dollars in sales annually and employs more than 15,700 people.

It has, however, evolved in a highly organic manner, growing quickly in some areas, less so in others. It has used a range of production systems, developed through incremental trial and error processes, and has oriented itself around a wide array of domestic and international market niches. Once composed of a large number of small-scale operators, the sector has undergone considerable consolidation to the point that it now includes several very large companies as well. Government stewardship of the industry has evolved in an equally ad hoc manner, with the result that the sector is now governed by a complex range of laws, regulations, policies and operational guidelines. In short, despite the fact that aquaculture now accounts for close to 30 per cent of the total value of fish and seafood production and landings in Canada—and is an active industry in all provinces and Yukon—there is no national overarching strategic approach to ensure its ongoing sustainable development.

The National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI) has been designed to address this situation. The initiative sets out a comprehensive strategic vision for the sector as well as a series of specific actions needed to achieve it. It represents the combined views of federal and provincial/territorial agencies as well as those of a wide range of aboriginal groups, industry, and other public stakeholders. It includes this overarching document and a set of five more detailed Strategic Action Plans focussed on the east and west coast finfish and shellfish aquaculture sectors, as well as the freshwater sector at the national scale. This overarching document provides a context for the plans, sets out a vision for the sector, and summarizes the key actions to be undertaken in advancing toward this vision. It is a document that has been formally endorsed by the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM), and is supported by aquaculture industry associations and many other observers. It is not a binding document in any way, but is rather a roadmap that charts a path toward a more environmentally, socially and economically sustainable aquaculture sector in Canada.

The National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI) has been designed to address this situation. The initiative sets out a comprehensive strategic vision for the sector as well as a series of specific actions needed to achieve it. It represents the combined views of federal and provincial/territorial agencies as well as those of a wide range of aboriginal groups, industry, and other public stakeholders. It includes this overarching document and a set of five more detailed Strategic Action Plans focussed on the east and west coast finfish and shellfish aquaculture sectors, as well as the freshwater sector at the national scale. This overarching document provides a context for the plans, sets out a vision for the sector, and summarizes the key actions to be undertaken in advancing toward this vision. It is a document that has been formally endorsed by the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM), and is supported by aquaculture industry associations and many other observers. It is not a binding document in any way, but is rather a roadmap that charts a path toward a more environmentally, socially and economically sustainable aquaculture sector in Canada.

Setting the Context

A Global Perspective on Aquaculture

Three major factors have contributed to making aquaculture the fastest-growing food sector in the world: 1) the rising global demand for fish and seafood due to population growth and increased consumer affluence; 2) declines in wild fisheries stocks; and 3) technological advances to improve husbandry techniques and enhance productivity for an increasing variety of species. Global aquaculture output is projected to continue to grow at a rate of about 4 per cent per year through 2030. With the output from capture fisheries remaining relatively constant, aquaculture output is expected to surpass 62 per cent of global seafood supply (captured and farmed) within 20 years.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has concluded that “public management of aquaculture is not dissimilar to public management of agriculture and, in developed economies, management and enforcement costs as a share of the value of the produce are lower for aquaculture than for capture fisheries.” Consequently, “public policy support for aquaculture is likely to grow worldwide.” Moreover, aquaculture development “has been of the win-win type, as both producers and consumers have gained when prices for cultured species have fallen as a result of increased production.”

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has concluded that “public management of aquaculture is not dissimilar to public management of agriculture and, in developed economies, management and enforcement costs as a share of the value of the produce are lower for aquaculture than for capture fisheries.” Consequently, “public policy support for aquaculture is likely to grow worldwide.” Moreover, aquaculture development “has been of the win-win type, as both producers and consumers have gained when prices for cultured species have fallen as a result of increased production.”

Aquaculture in Canada

Commercial aquaculture in Canada began more than 50 years ago with trout farming in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia and oyster farming in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia. During the 1980s, aquaculture output increased dramatically, mainly due to growth in salmon farming in British Columbia and New Brunswick. Commercial aquaculture operations now exist in every province as well as in Yukon, and the sector accounts for nearly 30 per cent of the total value of fish and seafood production and landings in Canada. Today, Canadian aquaculture operations harvest close to 145,000 tonnesFootnote 1 of product per year. Yet this is a small fraction of global production. Canada ranks 23rd among world aquaculture producers, and contributes less than 0.3 per cent of total output.

Commercial aquaculture in Canada began more than 50 years ago with trout farming in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia and oyster farming in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia. During the 1980s, aquaculture output increased dramatically, mainly due to growth in salmon farming in British Columbia and New Brunswick. Commercial aquaculture operations now exist in every province as well as in Yukon, and the sector accounts for nearly 30 per cent of the total value of fish and seafood production and landings in Canada. Today, Canadian aquaculture operations harvest close to 145,000 tonnesFootnote 1 of product per year. Yet this is a small fraction of global production. Canada ranks 23rd among world aquaculture producers, and contributes less than 0.3 per cent of total output.

Figure 1.

Canadian aquaculture output by species and province in 2008 (metric tonnes)Footnote 2.

Figure 1 presents two pie charts summarizing Canadian aquaculture output in metric tonnes by species and province for the year 2008. The first pie chart breaks down output by species as follows: salmon 72.8%; mussels 13.6%; Oysters 5.2%; trout 5.1%; other finfish 2%, and other shellfish 1.3%. The second pie chart breaks down output by province as follows: British Columbia 54.2%; New Brunswick 16.8%; Prince Edward Island 11.9%; Newfoundland and Labrador 7%; Nova Scotia 4.4%; Ontario 3.7%; Quebec 1.1%; Prairies 0.9%.

Salmon is the main species produced on Canadian farms, accounting for 73 per cent of total production volume, followed by mussels (14 per cent), oysters (5 per cent), trout (5 per cent) and other finfish and shellfish (3 per cent). British Columbia contributes the most farm-raised fish and seafood, followed by New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. In the inland provinces, trout is the main product, accounting for more than 92 per cent of total production. Ontario is the largest producer, followed by Quebec and the Prairie Provinces (see Figure 1).

Aquaculture production provides approximately 6,000 direct, full-time-equivalent (FTE) jobs for Canadians and some 9,700 more positions in the supplies, services and support sectors. With a gross value of more than $2.1 billion, the Canadian aquaculture industry contributes significantly to the broader Canadian economy, providing more than $1 billion toward Canada's direct, indirect and induced gross domestic product (GDP)Footnote 3. Moreover, aquaculture occurs primarily in Canadian coastal and rural communities—areas where other economic development opportunities can be limited and elusive.

Canada’s capacity to develop aquaculture has been recognized and encouragedFootnote 4 since the first National Aquaculture Conference in St. Andrews, New Brunswick in 1983. Canadian aquaculture still has considerable untapped potential. Indeed, Canada has the potential to be a significant global player in commercial aquaculture and a leading contributor to the development and promotion of sustainable aquaculture technologies. With a vast biophysical resource base, experience and expertise in the production, processing, distribution and marketing of fish and seafood, and coastal infrastructure to expand upon, Canada is well positioned to become an international leader in the production of farm-raised fish and seafood. Its ability to do so will depend on prudent environmental stewardship, a modern and robust regulatory management regime and engagement of aboriginal groups and other communities and sectors of society.

Renewing the Framework for Canadian Aquaculture – The National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI)

In June 1999, the federal and provincial/territorial governments jointly endorsed the Agreement on Interjurisdictional Cooperation with Respect to Fisheries and AquacultureFootnote 5 to foster improvement in intergovernmental relations with respect to the development and management of ecologically sustainable and economically viable fisheries and aquaculture industries. In the spirit of cooperation, governments agreed to pursue opportunities where increased transparency, accountability, and coordination would foster mutually beneficial improvements for both orders of government, with particular emphasis on the pursuit of a harmonizedFootnote 6 approach to the development of fisheries and aquaculture policies and objectives. Through the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM), Ministers are intent upon:

- identifying and establishing common goals;

- coordinating public policy objectives;

- improving consultations and information sharing on interjurisdictional matters; and

- improving resource management and services to the sector and the public.

NASAPI has been developed in this context. Throughout 2009 and early 2010, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) led an extensive consultation process on behalf of CCFAM to solicit input from governments and interested stakeholders regarding the future development of sustainable aquaculture. More than 500 representatives from federal– provincial/territorial governments, producers, suppliers, First Nations and other aboriginal groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academia and other parties participated in approximately 30 workshops across the country. A background document was circulated ahead of these sessions to stimulate ideas and focus discussion. Views expressed in the sessions were recorded, synthesized, analysed and used to generate proposed Strategic Action Plans. These plans were in turn widely circulated and commented upon several times to yield the five Strategic Action Plans—one each for east coast finfish, west coast finfish, east coast shellfish, west coast shellfish and national freshwater. Finally, this overarching document summarizing the plans was produced and widely circulated for several rounds of comments and revision.

The plans are not merely government documents or industry strategies. On the contrary, they represent a suite of widely agreed-upon actions to be undertaken with the broader goal of advancing the sustainable development of aquaculture in Canada. By targeting precise and realistic objectives to be achieved within a five-year time frame, resources (people and money) will be directed toward those relevant initiatives agreed upon by jurisdictions that can deliver meaningful and progressive industry advancement in a strategic manner. It is expected that governments, industry, aboriginal groups and other sectors of society will collaborate where possible and appropriate to implement the listed actions in keeping with their respective mandates and resource levels. Progress in implementing the plans will be reported upon regularly, and the plans themselves will be updated and renewed as required.

The plans are not merely government documents or industry strategies. On the contrary, they represent a suite of widely agreed-upon actions to be undertaken with the broader goal of advancing the sustainable development of aquaculture in Canada. By targeting precise and realistic objectives to be achieved within a five-year time frame, resources (people and money) will be directed toward those relevant initiatives agreed upon by jurisdictions that can deliver meaningful and progressive industry advancement in a strategic manner. It is expected that governments, industry, aboriginal groups and other sectors of society will collaborate where possible and appropriate to implement the listed actions in keeping with their respective mandates and resource levels. Progress in implementing the plans will be reported upon regularly, and the plans themselves will be updated and renewed as required.

Principles

NASAPI is modeled on sustainable development as defined in "Our Common Future" by the Brundtland Commission (1987); that is, "...development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

Successful implementation of NASAPI is expected to generate improved public, investor, and consumer confidence in the sector. The sector’s ability to attain this objective depends on the collaborative efforts of producers, suppliers, governments, First Nations and other aboriginal groups, communities and interested stakeholders. Such collaboration is required to establish a framework to advance aquaculture based on the three principles of sustainable development, which inherently build upon each other (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework to advance aquaculture based on the three principles of sustainable development.

Figure 2 provides a graphic illustration of a framework to advance aquaculture based on the three principles of sustainable development. The illustration consists of three boxes with arrows in between, pointing from left to right. The first box is labelled Environmental Protection, with a small description, i.e., mandating that maintenance of healthy and productive ecosystems is prerequisite for all aquaculture ventures. This box is followed by an arrow pointing left to right. The second box is labelled Social Well-being, with a small description, i.e., securing a social licence to operate. This box is followed by an arrow pointing left to right. The third box is labelled Economic Prosperity with a small description, i.e., responsible, market-driven sectoral growth and development.

The Strategic Action Plans outline areas where efforts are required to improve aquaculture public governance and private operations. Effective and wellcommunicated governance enhances public confidence in government oversight of industry activities, leading to an improved social licenceFootnote 7. In turn, this will lead to increased investor confidence in aquaculture, stimulating responsible and sustainable growth that creates economic prosperity.

The Strategic Action Plans outline areas where efforts are required to improve aquaculture public governance and private operations. Effective and wellcommunicated governance enhances public confidence in government oversight of industry activities, leading to an improved social licenceFootnote 7. In turn, this will lead to increased investor confidence in aquaculture, stimulating responsible and sustainable growth that creates economic prosperity.

The three interconnected principles of sustainable development—a concept now familiar to businesses as the “triple bottom line”— are depicted graphically by overlying circles (see Figure 3). As illustrated, development is only sustainable when all three principles are incorporated into a project. In the absence of one element—such as the social component—development may be viable, but not truly sustainable.

Figure 3.

Graphic illustration of the three inter-related components of sustainable development.

Figure 3 provides a graphic illustration of a sustainable development model that includes three components: Environmental, Social, and Economic. The illustration depicts three overlapping circles. In the middle, where all three circles overlap, the word sustainable is written. There are three areas where only two of the circles overlap in the diagram. The first is between environmental and social, and the word bearable is written here. This means that when the environmental and social components exist, the development is bearable. The second overlap is between social and economic, and the word equitable is written here. The third overlap is between environmental and economic, and the word viable is written here.

To guide the pursuit of sustainable aquaculture development in Canada, the overall objectives for each of the three principles of sustainable development and the roles of industry and governments are summarized in the following chart.

| ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION | SOCIAL LICENCE | ECONOMIC PROSPERITY |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives | ||

|

|

|

| Roles—Governments | ||

|

|

|

| Roles—Industry | ||

|

|

|

Vision Statement and Strategic Objectives

In this context, the vision for NASAPI is:

Supplying quality products and generating rural and coastal prosperity through environmentally, socially and economically sustainable aquaculture development.

To achieve this vision, three principal areas for action are envisaged:

- Governance (regulatory and management regimes for sustainable development);

- Social licence and reporting; and

- Productivity and competitiveness.

Governments and industry are aligning resources to implement the strategic objectives and specific action items outlined in each of the detailed Strategic Action Plans. These initiatives focus attention and effort on areas in which improvements can be made in aquaculture operations and governance to advance the competitiveness and sustainability of Canadian aquaculture. The conceptual framework for NASAPI is summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The framework of the National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative.

Figure 4 provides a graphic illustration of the framework for the National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI). The diagram is comprised of several text boxes with interconnecting lines to show relationships between particular sections. For aesthetics, there is a map of Canada in the background, with each of the Provinces labelled. The first level includes three boxes. Moving horizontally from left to right, the first box is labelled British Columbia and contains two inset boxes, one labelled West Coast Shellfish, and the other labelled West Coast Marine Finfish. The second box is labelled National and contains one inset box labelled Freshwater. The third box is labelled Atlantic and Quebec and contains two inset boxes, one labelled East Coast Shellfish, and the other labelled East Coast Marine Finfish. Each of the three main boxes has a line connected to the bottom, which then join into one main line that connects down to the second level. The second level contains seven boxes that are lined up across a horizontal plane. Moving horizontally from left to right, the first box is labelled Implementation, and includes a description that says at the Regional, Provincial, and Territorial level, implementation will be handled through Memorandums of Understanding (MOU) and other mechanisms. The second box is labelled CCFAM, which stands for Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers. In the box, a list identifies the members, comprised of Federal, Provincial, and Territorial governments. The third box is positioned in the middle of the second level and connects to the line from the first level. It is labelled National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plans. The fourth, fifth and sixth boxes are stacked vertically on level two. The fourth box is labelled Industry, the fifth is labelled First Nations and Aboriginal Groups, and the sixth is labelled Other Stakeholders. The seventh and final box on the second level is labelled Performance Monitoring. It lists MOU Management Committees, and Sustainability Reporting. A line from the third box leads down to the third level. This main line breaks into three lines and each line then connects to one of the three boxes on the third level. The first box, moving horizontally from left to right, is labelled Governance. It contains a bulleted list including Environmental Management, Aquaculture Management, Introduction and Transfers of Aquatic Organisms, Navigable Waters Protection Act, On-site Inspection, Access to Wild Aquatic Resources for Aquaculture Purposes, Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program, and Other Regulatory and Governance Issues. The second box is labelled Social Licence and Reporting. It provides a bulleted list, including Public Engagement and Communication, which has sub-bullets of Transparent Information-sharing System, Aquaculture Sustainability Reporting, and Resource Mapping. The last bullet in this box covers Aboriginal Engagement in Aquaculture. The third and final box is labelled Productivity and Competitiveness. It contains a bulleted list, including Fish and Shellfish Health Management, Aquatic Invasive Species, Emerging Technologies, Aquatic Feeds, Alternative Species Development, Risk Management and Access to Financing, Infrastructure, Marketing and Certification, and Labour and Skills Development.

Among the action items identified, it is apparent that some fall within the scope of provincial/territorial jurisdiction, some lie within federal jurisdiction, and others are shared responsibilities that include roles for industry, First Nations and other aboriginal groups, and other stakeholders. Additionally, some action items are not necessarily pertinent in every province/territory. The intent of NASAPI is to foster cooperative aquaculture development. Therefore, implementation will be respectful of the legal roles and responsibilities of all jurisdictions.

The strategic objectives for the advancement of sustainable aquaculture development in Canada are summarized below for the three principal areas (governance, social licence and reporting, and productivity and competitiveness). Further detail regarding the strategic objectives and specific action items within each objective are presented in the Strategic Action Plans.

Governance

Aquaculture is an area of shared jurisdiction in Canada. In this context, the federal and provincial/territorial governments will work with industry, First Nations and other aboriginal groups and other stakeholders to address regulatory challenges pertaining specifically to the following matters:

- Develop consolidated environmental managementFootnote 8 frameworks based on sound scientific protocols in support of a streamlined and harmonized aquaculture site application and review process;

- Review and update the management framework for Introductions and Transfers of Aquatic Organisms (pending implementation of the National Aquatic Animal Health Program);

- Review and renew national policies and guidelines for aquaculture site applications under the Navigable Waters Protection Act;

- Review federal and provincial/territorial on-site inspection requirements for each class of aquaculture operations and establish procedures to streamline and harmonize inspection and reporting protocols;

- Conduct the mandated review of the Access to Wild Aquatic Resources for Aquaculture Purposes Policy and identify mechanisms to ensure that the aquaculture sector has equitable access to wild aquatic resources;

- Modernize the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program to make it more responsive to the needs of markets and producers and to facilitate government management of the program; and

- Address other regulatory and governance issues pertinent to sustainable aquaculture development, including clarifying the rights and obligations of aquaculturists who operate in public waters and addressing matters that unduly hinder operational efficiency.

Social Licence and Reporting

In all sectors of Canadian aquaculture, it is imperative that producers build and maintain local and regional community support for their activities. Commonly referred to as maintaining social licence, this work involves a wide range of communication and engagement activities designed to ensure that the media, communities and the public are well-informed about the industry in general and its specific operations in particular. The following strategic objectives are seen as key means of doing so:

- Develop a more transparent system for gathering and sharing information to keep Canadians informed about the environmental, social and economic sustainability of aquaculture operations;

- Utilize resource mapping to improve planning for aquaculture development in public waters in a manner that is respectful of the equitable interests of all resource user groups; and

- Explore mechanisms and strategies for engaging aboriginal groups in the implementation of NASAPI and generate awareness of opportunities for expanded engagement in aquaculture development amongst First Nations and other aboriginal groups.

Productivity and Competitiveness

Governments in Canada have long held the view that it is important to foster and support innovation in aquaculture as a key means of enhancing competitiveness and sustainability within the sector. Developing new technologies and practices or adopting them from abroad, will improve environmental performance, reduce production costs, improve sector competitiveness, and generate greater value from Canadian aquaculture products. In this context, the following strategic objectives are intended to advance aquaculture productivity and competitiveness:

- Outline regional or provincial/territorial strategies to coordinate fish and shellfish health management procedures throughout the sector, including a renewed policy and regulatory approach to facilitate the administration of fish health and biofouling control products within the conservation and protection mandate of the Fisheries Act;

- Adopt a pest management approach to deal with aquatic invasive species, including a renewed regulatory framework to facilitate the administration of appropriate products and practices within the conservation and protection mandate of the Fisheries Act;

- Foster the development and implementation of innovative emerging technologies and practices, most notably related to broodstock development, recirculating aquaculture systems, integrated multitrophic aquaculture, mechanization, and systems for use at high-energy sites;

- Improve the quality and availability of sustainable aquatic feeds in Canada and develop predictive models to advance environmental regulation and management;

- Define strategies to advance alternative species development for a short list of finfish and shellfish that have been extensively researched and which offer potential for commercialization within a short to medium time frame;

- Improve risk management and access to financing by fostering the widespread adoption of best management practices, incorporating benchmarking, and reviewing the constraints associated with conventional financing to facilitate access to capital and stock insurance for aquaculture;

- Identify infrastructure requirements to facilitate sustainable aquaculture development and promote infrastructure projects that support the sector;

- Support industry to adopt international market access and certification programs and to implement generic marketing programs, as appropriate; and

- Outline human resource strategies and programs for labour and skills development leading toward a well-trained and productive workforce.

Implementation

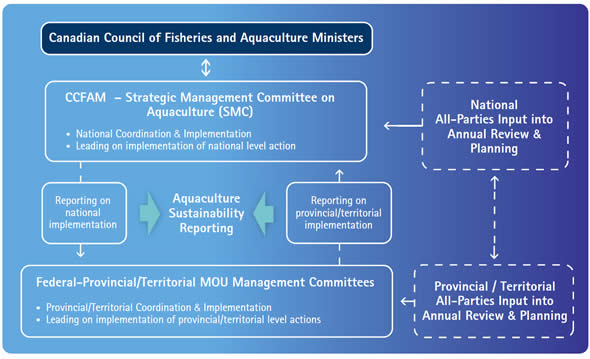

Implementation of NASAPI will utilize existing mechanisms for aquaculture governance and management. The implementation structure is illustrated in Figure 5 and described below.

The following principles will guide the implementation process:

- Each government partner shall remain accountable to its jurisdiction;

- Federal–provincial/territorial bilateral aquaculture Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) Management Committees will prioritize actions, agree upon timeframes, and coordinate implementation efforts;

- Implementation will occur in accordance with the resources available within each jurisdiction where agreed upon, i.e., the process is intended to help direct resources toward areas of need and priority within each province/territory; and

- Performance measurement will facilitate implementation by helping to keep the plan(s) current and identifying constraints.

Figure 5.

Implementation structure for the National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative.

Figure 5 provides a graphic illustration of the implementation structure for the National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI). This is represented by a flow diagram consisting of several boxes, each attached to the other by arrows. At the very top of the diagram is a box labelled Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM). It is attached to the main flow diagram by a dual direction arrow. The next four boxes form a square that flows counter clockwise. At the top of this square, and directly below the CCFAM box is a box labelled CCFAM – Strategic Management Committee on Aquaculture (SMC). This box contains two bullets, including National Coordination and Implementation, and Leading on Implementation of national level action. An arrow heading away from this box leads to a box labelled Reporting on national implementation. An arrow then connects to the next box, forming the bottom of the square diagram, and labelled Federal, Provincial and Territorial MOU Management Committees. This box contains two bullets, including Provincial and Territorial Coordination and Implementation, and Leading on implementation of provincial and territorial level actions. This box connects via an arrow to the next box, which is labelled Reporting on provincial and territorial implementation. An arrow then connects back to the original box to complete the square. In the center of the square, between the two reporting boxes, is the label Aquaculture Sustainability Reporting. To the right of this square flow diagram are two boxes stacked vertically that are indicated by broken lines. The top box has an arrow that points to the top of the square diagram and is labelled National All-Parties Input into Annual Review and Planning. The bottom box has an arrow that points to the bottom of the square diagram and is labelled Provincial and Territorial All-Parties Input into Annual Review and Planning. These two boxes on the right side also have a dual direction broken line arrow between them.

MOU Management Committee: Roles and Responsibilities

The federal–provincial/territorial management framework established through bilateral aquaculture MOUs or other similar mechanisms will serve as the key means for coordinating government efforts to advance the objectives of NASAPI. These MOUs typically establish federal–provincial/territorial management committees whose members will prioritize NASAPI implementation actions in their respective provinces/territories. Those items deemed to be national in scope will be presented to the CCFAM Strategic Management Committee on Aquaculture (SMC) for consideration. The MOU Management Committees will also address the need for a provincial/territorial planning and review process that would provide stakeholders with appropriate opportunity to have input into the annual review and planning for NASAPI implementation.

Time frames for completion of the action items will be reviewed and agreed upon by each of the bilateral MOU Management Committees. Additionally, these committees will determine which of the potential contributing partners will participate in implementation, including which partner should take the lead and which will play supporting roles. Each bilateral MOU Management Committee will prepare an annual progress report to be shared with CCFAM Strategic Management Committee to summarize initiatives and progress during the previous fiscal period.

Within each committee, the lead provincial/territorial department or ministry for aquaculture will be responsible for ensuring that the other provincial/territorial departments and ministries that have roles and responsibilities respecting aquaculture are duly engaged in the committee’s activities. Similarly, DFO’s regional offices will assure that the appropriate federal departments and agencies are engaged at the regional level.

While the provinces and territories are referred to collectively throughout this document, it is important to recognize that not all of the actions items within this plan will necessarily apply to all provinces and territories. Many of the action items are in various stages of development and implementation under existing cooperative mechanisms, particularly those targeted for completion within the first and second years.

CCFAM Strategic Management Committee (SMC): Roles and Responsibilities

The CCFAM framework is a logical mechanism for achieving national NASAPI objectives. The CCFAM SMC is composed of senior managers who represent each province/territory and the federal government. It will serve as the key strategic management body for overseeing the implementation of NASAPI, for prioritizing action items, and for keeping deputy ministers and ministers apprised of progress. CCFAM SMC will also consider the need for a national planning and review process that would provide producers, processors, suppliers, NGOs, First Nations, other aboriginal groups, and public stakeholders with appropriate opportunities to have input into aquaculture planning and management.

CCFAM SMC will prepare an annual progress report pertaining to national issues to be shared with the MOU Management Committees to summarize initiatives and progress during the previous fiscal period. It will also be the responsibility of CCFAM SMC to consolidate the provincial/territorial and national summaries into an annual progress report on the implementation of NASAPI and the sector-specific Strategic Action Plans.

Conclusion

In summary, the National Aquaculture Strategic Action Plan Initiative (NASAPI) sets out a vision for the sustainable development of aquaculture in Canada and describes a suite of actions needed to achieve that vision. It is expected that successful implementation of the various actions will, taken together, foster sustainable aquaculture development throughout Canada.

Endorsement of NASAPI by the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM) is testimony to the intent of the federal and provincial/territorial governments to advance sustainable aquaculture development where agreed upon by jurisdictions and for the benefit of all Canadians.

The five specific Strategic Action Plans present a comprehensive list of actions identified as a result of a wide range of information received through extensive stakeholder consultation and input as well as extensive government analysis of the various opportunities and challenges for the sector. The action items target specific issues intended to enhance industry sustainability and competitiveness. They present an opportunity to advance sustainable aquaculture development in the most strategic manner possible. The Strategic Action Plans are directional, living documents that are both flexible and adaptive. They respect federal, provincial, and territorial jurisdictions, build on existing plans and implementation mechanisms, and reflect regional circumstances and priorities. Through regular reviews, the plans will be updated to reflect those initiatives that have been completed and to accommodate new issues that emerge.

The five specific Strategic Action Plans present a comprehensive list of actions identified as a result of a wide range of information received through extensive stakeholder consultation and input as well as extensive government analysis of the various opportunities and challenges for the sector. The action items target specific issues intended to enhance industry sustainability and competitiveness. They present an opportunity to advance sustainable aquaculture development in the most strategic manner possible. The Strategic Action Plans are directional, living documents that are both flexible and adaptive. They respect federal, provincial, and territorial jurisdictions, build on existing plans and implementation mechanisms, and reflect regional circumstances and priorities. Through regular reviews, the plans will be updated to reflect those initiatives that have been completed and to accommodate new issues that emerge.

Electronic copies of the five Strategic Action Plans are available at the following web locations:

- East Coast Shellfish Sector Strategic Action Plan

- East Coast Marine Finfish Sector Strategic Action Plan

- Freshwater Sector Strategic Action Plan

- West Coast Shellfish Sector Strategic Action Plan

- West Coast Marine Finfish Sector Strategic Action Plan

- Date modified: