Evaluation of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s activities in support of Aquatic Species at Risk

Final report

Project number 96521

September 16, 2021

Table of contents

- 1.0 Evaluation context

- 2.0 Program context

- 3.0 Evaluation findings:

- 4.0 Conclusions and recommendations

- 5.0 Annexes

- Footnotes

Note: The Evaluation of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Activities in Support of Aquatic Species at Risk has an alternative report format that uses graphics and visuals, and which is available in PDF format: [insert PDF link].

1.0 Evaluation context

1.1 Evaluation context, objectives, and scope

The evaluation was intended to provide support to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) senior management in making evidence-based decisions and to identify challenges and opportunities for the management and delivery of activities in support of aquatic species at risk. The evaluation focused on activities that are funded by the Species at Risk Program (SARP).

The complexity of delivering the Species at Risk Act (SARA) requires a wide range of knowledge and expertise from across DFO as well as from external partners. SARP is responsible for delivering on DFO’s legislative requirements and aquatic species at risk-related priorities, but requires a holistic and collaborative approach with internal partners across the department to achieve results. Internal partners are involved extensively in various processes and SARP provides funding to support species at risk activities undertaken by these partners. Through three Grants and Contributions (Gs&Cs) programs, external partners also play an important role in implementing protection and recovery actions for aquatic species at risk.

The evaluation covers fiscal years 2016-17 to 2020-21 (not including Budget 2021), complies with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and meets the obligations of the Financial Administration Act. It includes an assessment of governance, design and delivery, as well as three G&C programs that provide funding to external partners for activities in support of aquatic species at risk.

- Habitat Stewardship Program for Aquatic Species at Risk (HSP)

- Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (CNFASAR)

- Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk (AFSAR)

The evaluation was conducted by the Evaluation Division and includes all DFO regions: Newfoundland and Labrador, Maritimes, Gulf, Quebec, Ontario and Prairie, Pacific, Arctic, and National Headquarters. This evaluation focuses solely on DFO’s activities in support of aquatic species at risk, including activities delivered both by Species at Risk Program and by other internal groups that receive funding from SARP. Activities of the other competent departments, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Parks Canada Agency (PCA), were not assessed. Findings from this evaluation will feed into the horizontal evaluation to be led by ECCC in 2022-23.

The evaluation was designed as an implementation evaluation to help determine whether activities are being implemented as intended and to provide evidence on what is working well and if any adjustments are required. Activities in support of aquatic species at risk are delivered by SARP itself, but also by a large number of internal partners that receive funding from SARP and by external partners funded through Gs&Cs programs.

Evaluation questions

Seven (7) questions guided the evaluation:

Governance

- Are the governance and financial management of DFO’s activities in support of aquatic species at risk effective?

- Do SARP-funded activities delivered by internal partners align with SARP priorities?

Design and delivery

- Are there legislative/policy tools that could be further explored to support the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk?

- Are SARP and its processes supporting the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk?

- What improvements could be made to enhance the SARP design and delivery?

Gs&Cs programs

- Do the Gs&Cs programs support the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk?

- Are the Gs&Cs programs accessible and inclusive?

Evaluation methodology

To answer the evaluation questions, the following lines of evidence were used:

- document and file review

- survey

- interviews

- administrative data review

- financial analysis

For full details on evaluation methodology, including limitations, please see Annex A.

2.0 Program context

2.1 Species at Risk Act (SARA)

SARA exists to:

- prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct

- provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity

- manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened

Three federal departments have primary responsibilities for implementing SARA

- Parks Canada Agency (PCA): manages species found in or on federal lands it administers

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO): manages aquatic species other than for those individual species found in Parks Canada managed waters

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC): manages all other species, including migratory birds

The Minister of ECCC has overall responsibility for administration of the Act. The Minister of DFO and the Minister of ECCC share responsibilities if the species is found both inside and outside areas managed by PCA.

The federal government is responsible for “sea coast and inland fisheries”, however, overlap with provincial jurisdiction necessitates involvement from both levelsof government (e.g. water use, forestry).

2.2 Species at Risk Program

Within DFO, SARP is managed by the Biodiversity Management Directorate within the Aquatic Ecosystems Sector, and is funded through A-base and B-base funding.

Figure 1: SARP actual salary, operation and maintenance (O&M), and Gs&Cs programsFootnote 1 expenditures have increased since 2016-17 ($ in millions)

Description

The line graph shows SARP actual expenditures for salary, operations and maintenance (O&M), and Gs&Cs programs (in millions). All lines show an increase since 2016-17. However, with new funding received from Budget 2018 there is a large increase for Gs&Cs in that year.

In 2016-17, total expenditures were $25.1 million. Salary was $11.5 million, O&M was $7.6 million, and Gs&Cs was $5.9 million.

In 2017-18, total expenditures were $25.1 million. Salary was $12.5 million, O&M was $6.8 million, and Gs&Cs was $5.8 million.

In 2018-19, total expenditures were $30.5 million. Salary was $15.7 million, O&M was $10.2 million, and Gs&Cs was $4.6 million.

In 2019-20, total expenditures were $46 million. Salary was $18.9 million, O&M was $10.7 million, and Gs&Cs was $16.3 million.

In 2020-21, total expenditures were $53.5 million. Salary was $21.7 million, O&M was $11.9 million, and Gs&Cs was $19.9 million.

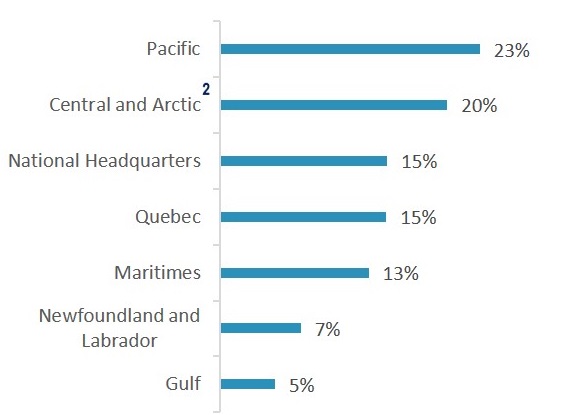

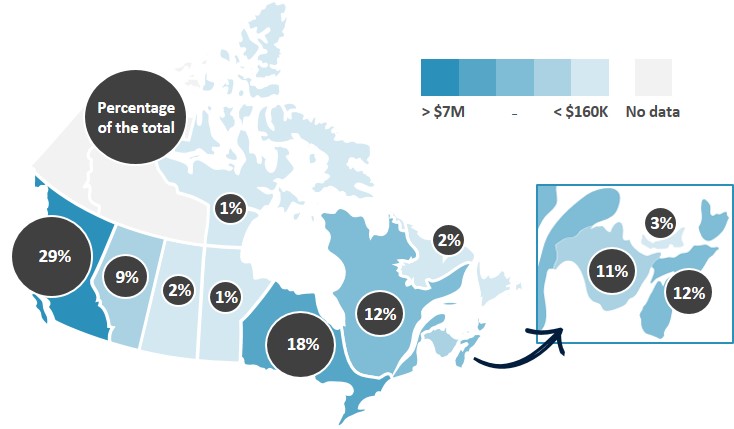

Figure 2: SARP expenditures by regionFootnote 2, excluding Gs&Cs programs, 2016-17 to 2020-21

Description

The bar graph depicts the distribution of SARP expenditures by region, excluding Gs&Cs programs between 2016-17 and 2020-21.

Pacific region: 23%

Central and Arctic* region: 20%

National Headquarters: 15%

Quebec region: 15%

Maritimes region: 13%

Newfoundland and Labrador region: 7%

Gulf region: 5%

* The creation of Arctic Region was announced in October 2018. However, for the evaluation, references to Central and Arctic include both the Arctic and the Ontario and Prairie Regions.

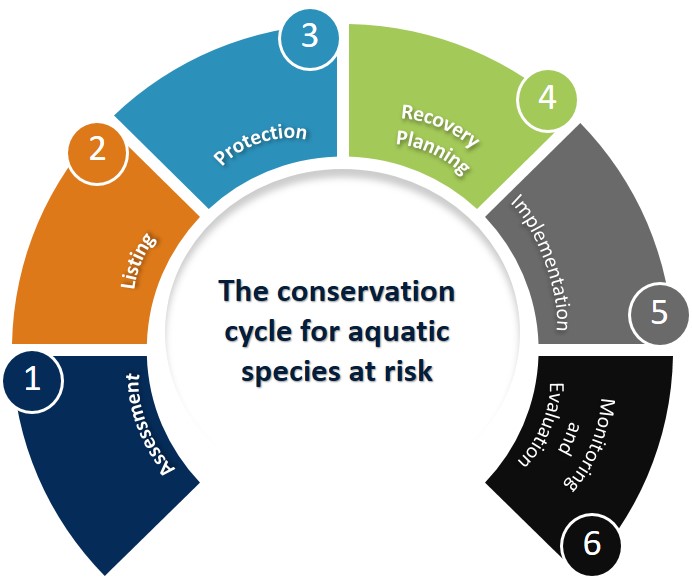

2.3 Working towards the recovery of aquatic species

The ultimate objective of SARP is the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk. To reach this goal, a range of interconnected activities occur throughout the conservation cycle for aquatic species at risk. The conservation cycle has six stages: Assessment, Listing, Protection, Recovery Planning, Implementation, and Monitoring and Evaluation.

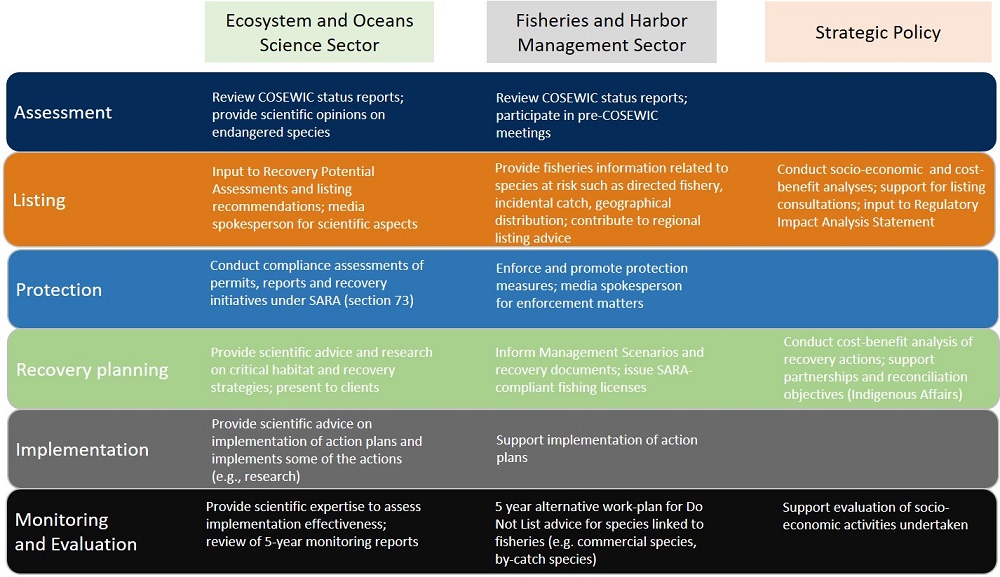

Figure 3: Conservation cycle for aquatic species at risk

Description

The figure depicts the conservation cycle for aquatic species at risk in six phases. Assessment, Listing, Protection, Recovery Planning, Implementation, and Monitoring & Evaluation.

- Assessment: The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC – arms-length scientific assessment body) assesses species as extinct, extirpated, endangered, threatened or of special concern (or find it to be data deficient, or not at risk).

- Listing: DFO develops advice on whether to list or not list an at-risk species, or refer the species back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration. The advice is provided to the Minister of DFO who then advises the Minister of ECCC on the aquatic species listing recommendations to the Governor-in-Council for decision.

- Protection: Species protection under SARA begins when the Governor in Council adds a species to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk under SARAFootnote 3. This can take multiple forms, including s.32 prohibitions under SARA.

- Recovery planning: Once a species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk, SARA requires that a recovery strategy and associated action plan(s) or a management plan is completed to identify actions for recovering at risk species.

- Implementation: Recovery actions are implemented by DFO and by partners and stakeholders from across Canada. Actions to conserve and recover aquatic species at risk are also supported through three primary G&C programs: Canada Nature Fund for Species at Risk, Habitat Stewardship Program for Aquatic Species at Risk, and Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk.

- Monitoring and evaluation: Protection and recovery measures are examined to determine whether they have contributed to abating threats and improving the species status in order to identify where further action may be needed. The program is required to post progress reports on the status of implementation for recovery strategies and action plans.

2.4 DFO Partners in delivering Aquatic Species at Risk activities

The complexity of delivering SARA requires a wide range of knowledge and expertise from across DFO at all stages of the conservation cycle. SARP is responsible for delivering on DFO’s legislative requirements and species at risk-related priorities, but requires a holistic and collaborative approach with internal partners across the department to achieve results. Some partners are involved extensively in multiple stages of the conservation cycle for aquatic species at risk and SARP provides funding to support the species at risk activities undertaken by these partners.

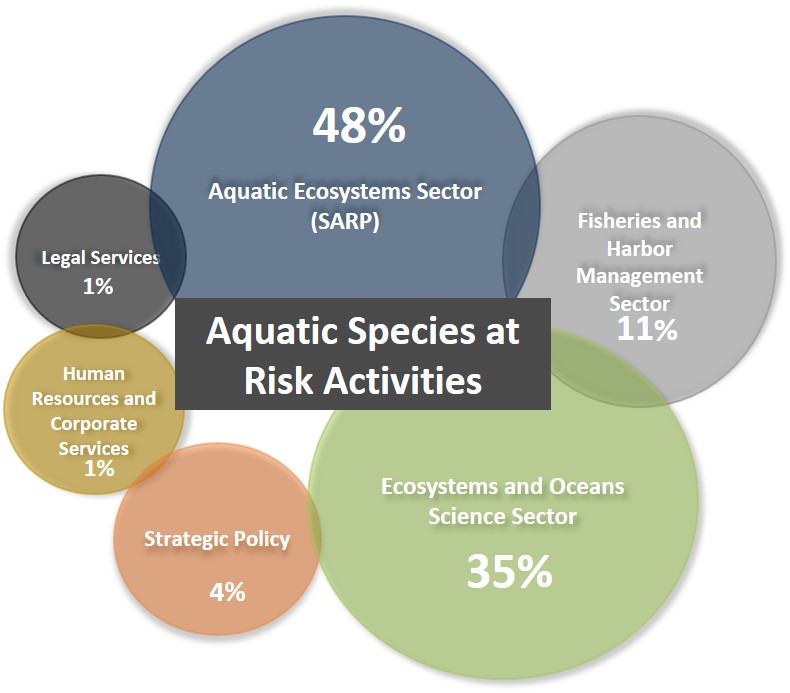

Figure 4: Allocation of SARP expenditures by DFO sector in %, 2016-17 to 2020-21.

Description

The figure depicts the allocation of SARP expenditures (as a percentage) by DFO sector between 2016-17 to 2020-21.

48% went to Aquatic Ecosystems Sector

35% went to Ecosystems and Oceans Science Sector

11% went to Fisheries and Harbour Management Sector

4% went to Strategic Policy

1% went to Legal Services

1% went to Human Resources and Corporate Services

More than 50% of SARP actual expenditures were spent by partner sectors to support species at risk activities.

As a good practice, in most regions, SARP has yearly service level or collaborative agreements with other sectors. While these are not standardized across the regions, they generally outline roles and responsibilities, financial information (FTEs, Salaries and O&M implicated), and deliverables pertaining to species at risk-related activities.

The following describes some of the activities undertaken by other DFO sectors related to aquatic species at risk.

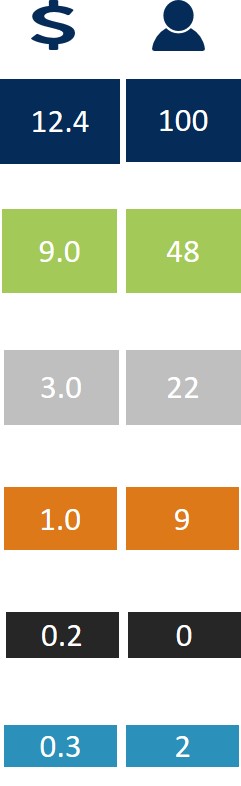

Figure 5: SARP total expenditures have significantly increased in the past 5 years, especially in the Ecosystems and Oceans Science Sector (300%) and the Aquatic Ecosystems Sector (147%). This is mainly due to the introduction of Nature Legacy and the related funding. (Graph in millions $)

Figure 6: SARP five-year annual average expenditures in millions and SARP funded full-time employees by Sector Footnote 4

Aquatic Ecosystems

SARP leads on DFO’s SARA requirements and delivers two of the Gs&Cs programs (HSP and CNFASAR).

Ecosystems and Oceans Science

Provides scientific advice and peer-reviewed scientific information, gather information and conducts research as required for each stage of the conservation cycle.

Fisheries and Harbor Management

Enforces SARA after listing stage is complete, conducts engagement activities throughout the conservation cycle, and participates in recovery planning and implementation. Administers the AFSAR Gs&Cs program.

Strategic Policy

Provides socio-economic analyses and cost-benefit analyses to inform listing and recovery planning and implementation decisions.

Legal Services

Provides legal advice throughout the conservation cycle to support the administration of SARA and ensure all legal requirements are met.

Other internal and corporate services

Provides communication, corporate, human resources, financial, IT and other internal support services throughout the conservation cycle.

Detailed activities by Sector and conservation cycle stages are outlined in Annex B.

Description

The line graph depicts SARP expenditures (in millions) by sector between 2016-17 to 2020-21. The data is represented in the table below:

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Ecosystems | 10.3 | 10.7 | 12.1 | 13.8 | 15.2 |

| Ecosystems and Oceans Science | 4.7 | 4.9 | 8.9 | 12.1 | 14.2 |

| Fisheries and Harbour Management | 2 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4 |

| Strategic Policy | 1 | 0.76 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Legal Services | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0 | 0 |

| Other internal and corporate services | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

2.5 SAR Transformation

In response to new listed species being continuously added as COSEWIC continues its assessments and a need to prioritize efforts and investments, SARP has been engaging groups across the department on ways to modernize DFO’s approach to SARA delivery in order to improve the protection of aquatic species at risk through more holistic approaches.

This process is focused on exploring alternative approaches to SARA delivery, including multi-species, threats-based, and ecosystem-based approaches, as well as tools available in other legislation such as the Oceans Act and the Fisheries Act.

For DFO to transform the approach to implementing SARA, it is vital that all implicated sectors and partners are engaged and support the proposed approaches. SARP recognizes the need for buy-in and engagement of other sectors, and, in an effort towards meeting this goal, developed a shared vision in collaboration with all implicated sectors and regions. The shared vision was endorsed by senior management.

3.0 Evaluation findings

3.1 Governance

3.1.1 Roles and responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities are not clearly defined

Efforts to improve the governance of species at risk activities have been made. For example, the creation of a Biodiversity Management Director General position responsible for the Species at Risk and Aquatic Invasive Species programs and the splitting of SARP responsibilities between two directors at NHQ (Species at Risk Governance, Listing and Emerging Priorities, and Species at Risk Operations). However, there is a need to define roles and responsibilities for all levels of management within NHQ and in the regions related to species at risk activities.

Most interviewees identified the lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities as one of the program’s main weaknesses. An area where there appears to be a significant level of confusion around roles and responsibilities is with the recently created director-level positions in most regions. Directors have responsibility for SARP but also for other programs. The role and responsibilities of the directors do not seem to be clear or consistent across regions which leads to confusion at the operational level, and impacts the delivery of SARP. Moreover, there are challenges with prioritizing SARP activities which compete with other programs’ priorities under the responsibility of these directors.

Roles and responsibilities in National Headquarters

Many interviewees support a stronger and more well-defined role for SARP National Headquarters. NHQ can take more of a leadership role by continuing to set priorities, but also by providing more guidance to effectively manage the complexity of species at risk activities and the extensive collaboration required with partner sectors. Key areas where a need for increased guidance was identified include:

- details of roles, responsibilities and pathways of accountability for reporting

- requirements (versus good practices or optional pieces) for the various steps in the listing process, for example, requirements as per SARA

- managing regional differences of opinion regarding listing recommendations

- consulting with Indigenous groups in a way that supports broader efforts around reconciliation

Other challenges

SARP NHQ does not communicate consistently with the regions and is not always responsive to requests for status updates, particularly with regards to slow-moving files for which decisions need to be made at the NHQ level for work to continue. This has created a perceived lack of transparency from NHQ, and has resulted in confusion on the part of staff and partner sectors, which sometimes leads to inefficiencies and duplication of work.

Communication between regional SARP directors and NHQ is inconsistent and does not always follow a formal, standardized process. For example, sometimes information flows through the Regional Director, but often information is received more informally through operational employees or from other regions who have received information from NHQ. Directors in the regions felt they do not always have a decision-making or leadership role in regard to SARP.

In the Pacific Region, a director-level position was not created. The complex reporting structure in place has led to inefficiencies and difficulties with accountability for SARP deliverables, due to oversight of employees who work on SARP activities being split between different groups.

3.1.2 Working with partners

Working with partners within DFO

In general, working relationships amongst regions and sectors are viewed positively. Views on communication within regions were generally positive, with meetings and discussions occurring regularly.

In most regions, SARP has yearly service level or collaborative agreements with other sectors. While these are not standardized across the regions, they generally outline roles and responsibilities, financial information, and deliverables. This is seen as a good practice; however, these agreements do not guarantee that the work will be completed in a timely manner due to competing priorities in other sectors.

In many cases, species’ habitats span across multiple regions, requiring many regions to work together. In these cases, one region becomes the lead and assumes a coordination role. Meetings across regions take place in order to share knowledge and advance files. However, the advancement of shared files can be slower due to competing priorities in different regions. Also, when there is a fundamental disagreement between regions on listing recommendations it can be difficult to resolve due to a lack of guidance and resolution process.

Working with external partners

Due to different jurisdictional authorities related to species at risk, SARP often works with Provincial/Territorial (P/T) partners and other federal departments. Relationships with P/Ts are complex due to challenges related to the division of responsibilities, expertise and information, and different priorities and authorities.

Collaboration with other federal departments/agencies was seen as helpful, however a more focused effort to work with them on integrating species at risk considerations into their activities at an early stage would benefit protection and recovery efforts. This could be particularly valuable in working with Departments:

- whose activities can impact species at risk

- that authorize activities that can impact species at risk

- other competent departments regarding the intersection of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems to support ecosystem-based approaches

In some cases, collaborative efforts are formalized through formal agreements. For example, SARP entered into Conservation Agreements with external partners, under section 11 of SARA, to formalize responsibilities and commitments for the protection and recovery of species at risk.

The Conservation Agreement to Support the Recovery of the Southern Resident Killer Whale (SRKW) formalized the participation of the marine industry and government to work collaboratively towards the development, implementation, monitoring, assessment and adaptation of voluntary measures to reduce the contribution of large commercial vessels to threats to SRKW.

3.1.3 Accountability for SARP funding to partners

The complexity of SARA requires a holistic and collaborative approach in which multiple partner sectors deliver species at risk activities and provide expertise and advice throughout each stage of the conservation cycle.

In 2020-21, SARP distributed nearly $20M to partner sectors. Some of this funding is for FTEs (salaries), and it is not always clear to what extent the staff in those funded positions are working on species at risk activities. It is difficult to validate that the SARP-funded work carried out by other sectors is being completed as planned, as SARP has to compete with the priorities of those sectors.

An analysis of SARP financial data showed that while the financial coding system is extremely detailed, it does not mitigate the risk that funds earmarked for SARP activities are used towards other sectors’ priorities, and it remains difficult to track SARP funds. Once SARP funds are transferred to other sectors, SARP no longer has authority over their use. While the program is accountable for all legal deliverables under SARA, many of those deliverables are dependent on work, advice and approvals from internal partners, which can affect the program’s ability to meet legislated timelines under SARA.

From the perspective of partner sectors the current funding arrangements between their sector and SARP is working well and generally, priorities related to species at risk are understood.

In most cases, SARP funding flows from NHQ to partner sectors in the regions, bypassing regional executives (Ontario and Prairie Region is an exception to this structure). While some regions use work plans and/or service level agreements to ensure other sectors understand their roles and responsibilities with regard to species at risk activities, there is no mechanism through which partner sectors can be held accountable for their agreed-upon species at risk-related work.

A different approach is being used in Ontario and Prairie region (previously Central and Arctic region)

Funding for species at risk activities in this region is received from NHQ and flows through regional SARP first, and then is allocated to each regional sector. The allocation occurs at the end of the fiscal year, based on the completion of deliverables as outlined in work plans.

Regional interviewees indicated that they are able to manage the funding to other sectors and adjust as necessary based on deliverables. Interviewees indicated that this allows the Ontario and Prairie Region to maintain accountability for species at risk deliverables and increases the level of oversight when they are dependent on other sectors to undertake activities related to these deliverables.

Improving accountability with internal partners

Key informants indicated that accountability for SARP funds could be improved by tying funding directly to SARP deliverables. It would be more effective if SARP management in the regions were able to exercise some control over the funds distributed to partners.

- for example, while SLAs and work plans with other sectors in the regions are currently seen as useful for providing clarity on roles, responsibilities and deliverables with partners, in order to be an effective tool to support accountability they need to be tied to funding. This would allow SARP to manage priorities and reach formal agreement on the desired outcomes, and would give the program the ability to ensure only species at risk deliverables are generated with SARP resources. If the sectors are unable to complete the agreed-upon work, the program could reallocate the funds and use this leverage to work with sectors to improve their ability to meet SARP’s needs

Key informants also suggested that accountability for species at risk deliverables should be a component of Performance Agreements for partners involved in species at risk activities, up to the Regional Director General/Assistant Deputy Minister level, in order to strengthen accountabilities for those deliverables.

Designating a national, senior-level species at risk champion, or creating a species at risk Secretariat, with the role of elevating the profile of species at risk activities in the department were amongst the suggestions provided by interviewees. This would help to create buy-in amongst internal partners, thus establishing species at risk activities as a priority for the whole department and improving accountability for species at risk deliverables.

3.1.4 Internal fora dedicated to Aquatic Species at Risk is needed

Many operational-level (i.e., manager level and below) interviewees indicated that the various existing working groups for species at risk are effective in helping them advance their SARA activities as they promote collaboration with other regions and sectors by providing an opportunity to share information and confirm priorities. Some of the working groups specifically identified were the Listing Working Group, Aquatic Pan-Canadian Approach Working Group, and Management Scenario Listing Group.

The Biodiversity & Ecosystems Management Oversight Committee (BEMOC) is the national, executive-level committee for discussions and decisions on SARP, but it is also the forum for other programs, e.g., Fish and Fish Habitat Protection Program (FFHPP) and Aquatic Invasive Species. Discussions are mostly related to FFHPP and, therefore, aquatic species at risk is generally not a focus of committee meetings. Additionally, for species at risk, BEMOC tends to be more of an information-sharing forum and generally does not focus on making high-level decisions or providing the guidance that is needed to address many complex issues related to the delivery of activities related to aquatic species at risk.

The Species at Risk National Advisory Committee (SARNAC) was identified as an effective forum for managers across the country to collaborate with each other and to share information received from NHQ. Some interviewees suggested that SARNAC be expanded to include regional SARP directors which would allow them to be aware of information shared by NHQ in a consistent and timely manner.

There was some support among key informants in terms of creating a national, executive-level forum focused solely on aquatic species at risk (in contrast to BEMOC which often does not allow for in-depth species at risk discussions), with decision-making capacity from across partner sectors. This type of forum could help improve consistency and clarity in roles and responsibilities, as well as priority setting to facilitate accountability of partner sectors, which will be particularly important in the context of SARP’s transformation efforts.

3.2 Design and delivery

3.2.1 Listing of Aquatic Species at Risk

Aspects of the listing process make it difficult to meet SARA timelines

Interviewees indicated that working through the various pieces of the listing process, while also respecting other Government of Canada priorities and obligations (for example, the reconciliation agenda), makes it very difficult to advance decisions within targeted timeframes and to meet the timelines prescribed by SARA. For example, staff find it challenging that thorough consultations with Indigenous groups, as well as internal and external reviews and approvals, can quickly exhaust these timeframes. This challenge is exacerbated by the fact that several aspects of the listing process implicate parties external to the department, over whom the program may have limited influence.

Internal approval processes are lengthy and at times convoluted, with documents required to go through several levels of input, review and approval within regions and at NHQ, and both within and outside the program. In some instances, these documents have received approval from other sectors at the regional level, but face challenges from the same sectors at the NHQ level. These challenges suggest issues with communication between the regions and NHQ, as well as a need for clear guidelines on responsibilities related to approval processes. Interviewees felt that streamlining internal approval processes is an important area to examine for potential efficiencies.

Ecosystems and Oceans Science (EOS) Sector is a major partner in the listing process, as they contribute peer-reviewed science data that informs listing advice. While the data provided is seen as very useful to SARP, there are some aspects that impede EOS’ ability to meet SARP requests. For example, interviewees from within SARP and EOS expressed that SARP’s requests for science data can be large, complex, and unclear which can impede EOS’ ability to effectively fulfill these requests. Improvements to the prioritization and clarity of SARP requests to EOS could assist the latter in managing and addressing these in a more efficient manner.

The Evaluation of DFO’s Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS)Footnote 5 (2018-2019) supports this finding, noting that there was a growing gap between the number of requests submitted to EOS by SARP and the number of requests fulfilled. Among the factors identified as challenging EOS’ ability to address SARP requests was complexity of the requests, as well as the formulation of the research questions (too broad, too complex, unclear, or beyond the scope of the CSAS).

Socioeconomic considerations can slow down or halt processes

Many interviewees, including both SARP staff and internal partners, indicated that a significant amount of work and time goes into listing processes for species that they believe are highly unlikely to be listed due to known socioeconomic considerations. This is generally something that program staff are aware of at the start of the process, and thus it is not seen as an efficient use of resources to go through a full listing process for these species.

Long timelines for decisions regarding the listing of species result in advice and consultations becoming outdated, necessitating additional advice and/or consultations, which in turn results in further delays to listing decisions. Interviewees provided the example of Atlantic Cod, which has been awaiting a listing decision for several years.

- an additional concern is that species awaiting a listing decision are not afforded the protections of SARA, but may also not be receiving the necessary focus and attention to prevent their decline under other legislative tools because they are caught up in the SARA listing process

Although the program is continuously trying to improve these processes, opportunities to streamline the listing process are limited by legislative and legal requirements, as well as Treasury Board policies and directives.

3.2.2 Protection of Aquatic Species at Risk

Conservation and protection

C&P is integral to protecting aquatic species at risk. There are approximately 650 C&P fishery officers across Canada who have been trained and designated as enforcement officers under SARA. Their SARA enforcement duties are undertaken alongside their duties under the Fisheries Act and other federal statutes and regulations.

Throughout the evaluation period, C&P fishery officers’ efforts to protect species at risk through the enforcement of SARA have been increasing as demonstrated through an increasing number of hours spent on species at risk activities.

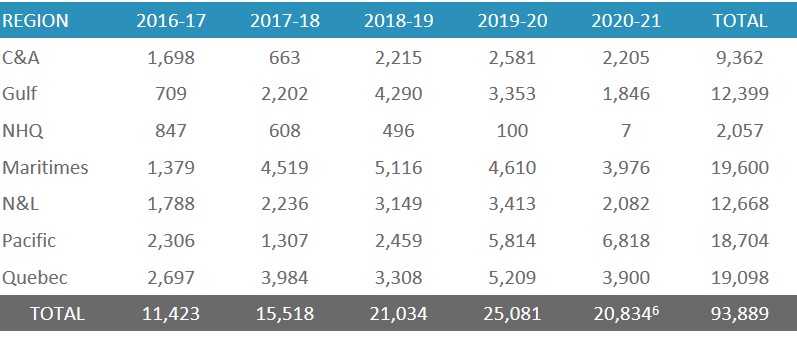

Figure 7: Number of hours C&P fishery officers spent on species at risk-related activities by region, 2016-17 to 2020-21Footnote 6

Description

The figure depicts a table with seven columns and nine rows. The columns represent a fiscal year and the rows represent a DFO region. At the end of each column and row there is a total for all five years of the evaluation.

Source: Conservation & Protection data. Not all hours are funded through SARP.

Over the evaluation period, C&P fishery officers discovered 176 SARA violations. Pacific Region is where a large majority (108 out of 176) of these violations occurred.

Figure 8: Number of SARA violations by region, 2016-17 to 2020-21

Description

The bar graph depicts the number of SARA violations by region between 2016-17 and 2020-21.

108 violations in Pacific region.

37 violations in Maritimes region.

12 violations in Central and Arctic region.

10 violations in Quebec region.

9 violations in Gulf region.

0 violation in Newfoundland and Labrador region.

Survey respondents indicated that the enforcement of SARA provisions and regulations is a significant factor contributing to the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk.

Innovation and technology in practice

The demands placed on C&P’s time from within the department are continuously increasing. In the absence of corresponding increases to C&P’s resources, these demands must be managed by balancing risks. Funding received through the Nature Legacy Initiative was helpful in expanding upon some compliance and enforcement for SARA-related activities in freshwater ecosystems from Ontario to British Columbia and in re-establishing the dive team in the Pacific Region.

One possibility in regards to improving the reach of conservation and protection work for species at risk is by training and deploying SARP staff as fishery guardians. This could ease the burden on C&P fishery officers while maintaining or even exceeding the current level of enforcement for species at risk.

C&P has implemented innovative practices and the use of technology to improve efficiency and effectiveness in verifying compliance with and enforcement of SARA. Examples from two regions are provided.

Newfoundland and Labrador region

- Time lapse cameras

- time lapse cameras are being deployed in the Region to monitor the capture of SARA-listed species on fishing vessels less than 65’. These cameras record which species are brought aboard and ensure that fishers are accurately reporting their catch. In the event of capturing a listed species, fishers are expected to return that species to the water in an efficient and safe manner

- for example, where fishers are permitted to capture only one tuna at a time, C&P cameras prevent fishers from catching and then releasing an under-sized tuna with the hope of catching a larger one

Pacific region

- Dive team

- there is a dive team of six fishery officers managed under Pacific Region’s Nature Legacy Program who assist with enforcement-related diving needs. This team regularly collects evidence, performs underwater inspections, and retrieves ghost fishing gear. Verifying compliance from under the water is especially useful for the purpose of SARA enforcement as it greatly increases C&P’s ability to detect violations that would go unseen above water

- for example, the dive team discovered an active illegal Northern Abalone harvest when the concurrent vessel inspection showed nothing of concern

- Swabbing for DNA

- during the course of an inspection, swabs of vessels and gear are routinely taken by C&P officers and then analyzed against the DNA of any listed species. This information serves primarily as intelligence to improve efficiency and to direct officers in the field.

3.2.3 Recovery planning for Aquatic Species at Risk

- recovery strategies identify what needs to be done to stop or reverse the decline of a species listed as threatened, endangered or extirpated

- action plans identify the measures to take to implement the recovery strategy for species listed as threatened, endangered or extirpated

- management plans identify objectives for maintaining sustainable population levels and identify measures for the conservation of species of ‘special concern’

Between 2016 and 2019, DFO posted a total of 20 proposed recovery strategies, 19 final recovery strategies, 61 proposed action plans, and 29 final action plans on the Species at risk public registryFootnote 7. While SARA requires that final versions of the recovery documents be available on the registry within 90 days of posting the proposed documents, SARP faces challenges meeting those timelines. Some delays are due to the extent of collaboration required with partners and the many layers of approval both within SARP and in partner sectors.

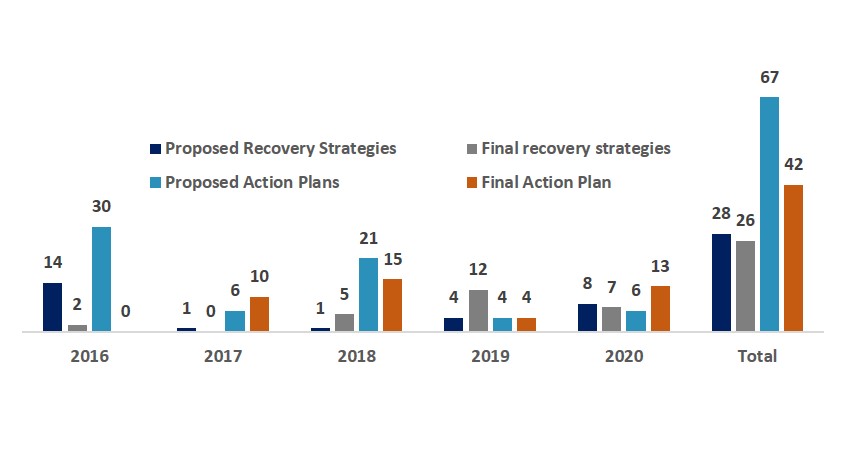

Figure 9: Recovery strategies and Action plans posted by DFO over the scope of the evaluationFootnote 8

Description

The bar graph depicts the number of recovery strategies and action plans posted by DFO over the scope of the evaluation.

In 2016, 14 proposed recovery strategies, 2 final recovery strategies, 30 proposed action plans, and 0 final action plans were posted.

In 2017, 1 proposed recovery strategies, 0 final recovery strategies, 6 proposed action plans, and 10 final action plans were posted.

In 2018, 1 proposed recovery strategies, 5 final recovery strategies, 21 proposed action plans, and 15 final action plans were posted.

In 2019, 4 proposed recovery strategies, 12 final recovery strategies, 4 proposed action plans, and 4 final action plans were posted.

A total of 93% (26/28) of recovery strategies were finalized during the evaluation time period, while 63% (42/67) of action plans have gone from proposed to final. In terms of the completion of Reports on Progress of Implementation, 62% (29/47) of eligible recovery strategies had an update, 58% (11/19) of eligible management plans had an update, and 0% (0/2) of the eligible action plans had an update.

The usefulness of recovery documents for advancing recovery actions is limited by a lack of specificity. Due to many external factors, the ability to influence the implementation of recovery measures is often outside of SARP’s or even DFO’s control, however, the main tools that SARP currently uses to guide and advance recovery actions are the recovery documents required by SARA. While SARA does specify some content to be included in recovery documents, it does not require that recovery actions be clearly defined to the point of being fully implementable. For example, recovery documents often do not clearly identify parties responsible for recovery actions, either inside or outside of the department, which in some cases may limit accountability for their completion.

A lack of knowledge regarding many species can prevent the implementation of more concrete recovery measures. Therefore, most identified recovery measures are focused on gathering much needed knowledge rather than recovering the species. More tangible recovery measures are usually designated to unnamed (and often not yet identified) external partners.

SARA requires a report on the progress of recovery document implementation within five years of posting. Sixty-two percent of eligible recovery strategies have a report on progress.

It is difficult to truly account for results that have been achieved through the implementation of recovery documents as performance measures and timelines are often not identified or sufficiently defined. Recovery actions also do not have defined targets or baseline data.

There are also some inefficiencies in regard to the recovery planning process. One aspect of this process that was identified as particularly inefficient is that all materials related to species at risk are generally routed to the Minister’s office for approval, even in cases where it may not be necessary. For example, final recovery documents where minimal changes have been made to the proposed version, or five-year progress updates.

Overall, recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans provide useful information on species but lack precision when it comes to the elements that guide the implementation of recovery actions. In particular, the identification of parties responsible for recovery actions, timelines for these actions, and the performance measures and targets that will be used to measure success need to be clear and specific in order for recovery documents to be effective tools in protecting and recovering species at risk.

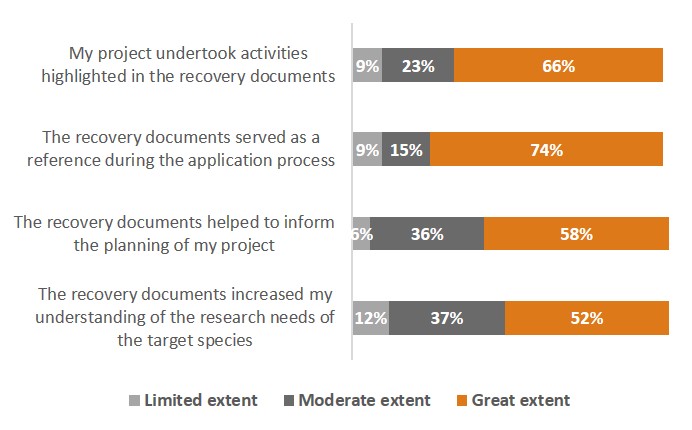

Despite the gaps in recovery documents outlined earlier, survey results showed that these documents are accessed by and useful to recipients of the Gs&Cs programs.

91% of survey respondents were aware of recovery documents for their target species.

“Our program’s activities are specifically recommended in DFO’s Resident Killer Whale, Transient Killer Whale, and Humpback Whale recovery strategies.” – Survey respondent

Figure 10 : The majority of recipients found recovery documents useful for their projects to a great extent

Description

The bar graph depicts the extent to which recipients found recovery documents to be useful for their projects in response to a series of survey questions.

In response to the question, “My project undertook activities highlighted in the recovery documents”, 9% of recipients selected “to a limited extent”, 23% selected “to a moderate extent”, and 66% selected “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The recovery documents served as a reference during the application process”, 9% of recipients selected “to a limited extent”, 15% selected “to a moderate extent”, and 74% selected “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The recovery documents helped to inform the planning of my project”, 6% of recipients selected “to a limited extent”, 36% selected “to a moderate extent”, and 58% selected “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The recovery documents increased my understanding of the research needs of the target species”, 12% of recipients selected “to a limited extent”, 37% selected “to a moderate extent”, and 52% selected “to a great extent”.

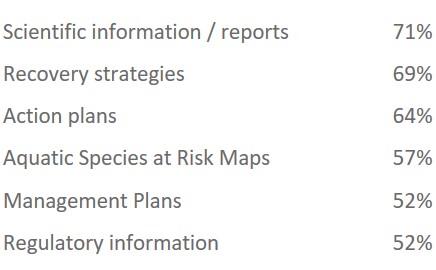

All three types of recovery documents (recovery strategies, action plans and management plans) were useful to Gs&Cs recipients, with a majority of those surveyed having used each type. It is worth noting that other resources made available by the federal government were also utilized by recipients, such as scientific information and aquatic species at risk maps.

Figure 11: Gs&Cs recipients are making use of resources developed by the federal government to support their projects

Description

The figure depicts what federal government resources Gs&Cs recipients are making use of to support their projects.

71% of recipients used Scientific information / reports to support their projects.

69% of recipients used Recovery strategies to support their projects.

64% of recipients used Action plans to support their projects.

57% of recipients used Aquatic Species at Risk Maps to support their projects.

52% of recipients used Management Plans to support their projects.

52% of recipients used Regulatory information to support their projects.

While these documents have been useful to many recipients, there is a perceived lack of clarity regarding responsibility for recovery actions. The majority of recipients indicated that while recovery documents identify a clear plan for the recovery of aquatic species at risk ‘to a moderate or great extent’, recovery documents only identify who is responsible for activities to a limited or moderate extent. Interviewees confirmed that this lack of clarity limits accountability for recovery actions and thus, progress of recovery measures.

3.2.4 Implementation of recovery actions

A need for direction on SARP’s role in implementation

There is a clear divergence of understanding and opinions on what SARP’s role is, and/or should be, when it comes to implementing recovery actions for aquatic species at risk. Unlike the other stages of the conservation cycle, SARA is not prescriptive in terms of the timing of or responsibility for implementing recovery actions. SARP’s ability to influence recovery measures is further complicated by factors that are outside the program’s (or even DFO’s) control, such as issues around jurisdictional authorities, pre-existing infrastructure, and the need to influence external parties to prompt action.

- there is a perception that SARP should take a greater hands-on role related to implementation of recovery actions, since staff within SARP have subject matter expertise that would be valuable for implementation

- some interviewees indicated that implementation is the role of other groups, both within and outside the department, while others stated that they simply do not understand SARP’s role

- many interviewees mentioned that more time and effort should be spent on implementing protection and recovery activities. DFO dedicates a large amount of time and effort to the listing process which is where most of the legal requirements of SARA are focused. In turn, this limits time and resources spent on protection and recovery activities

- recovery documents do not clearly delineate roles and responsibilities for implementation activities, which does not promote ownership for these activities. There is room for a greater leadership and coordination role for the program in the implementation of recovery actions

Existing templates and guidance materials are useful, but guidance is still needed in a few key areas

There are many templates and guidance materials to assist with work on species at risk, and key informants generally indicated that these materials are useful.

The program has made a concerted effort to address gaps in guidance materials, including through an internal SARP working group that is dedicated to this work.

There are still a few key areas where additional guidance is needed:

- with Indigenous engagement being a high priority for the Government of Canada, there is a need for guidance on how this priority relates to SARP, and how it should practically be included in SARP processe

- there is a lack of direction and guidance around the implementation of recovery actions and how this work should be carried out

- through their transformation efforts, SARP is moving away from looking at species in isolation and towards multi-species approaches that take into consideration common threats or ecosystems. While this work continues to evolve, it is worth noting that some interviewees indicated they require more guidance on multi-species approaches

Clarifying and communicating SARP’s role in the implementation of recovery actions would alleviate confusion and reconcile divergent opinions within and outside the program in this regard.

3.3 Gs&Cs programs

3.3.1 Nature of external investments

In an effort to improve outcomes for aquatic species at risk, DFO invests in external activities that contribute to the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk. For example, the department invests in these activities through three Gs&Cs programs – Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk, Habitat Stewardship Program for Aquatic Species at Risk, and Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk. For more detailed information on the Gs&Cs projects and their recipients, please see Annex C" at the bottom of the section.

Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (CNFASAR)

Part of Canada’s Nature Legacy Initiative, launched in May 2018, CNFASAR is funded to provide $55 million over five years to support projects that help to recover aquatic species at risk. Its objective is to slow the decline of aquatic species at risk and enable a leap forward in species recovery through targeted funding for recovery activities for priority places, species and threats.

Habitat Stewardship Program for Aquatic Species at Risk (HSP)

HSP was established in 2000 as part of Canada's National Strategy for the Protection of Species at Risk. It was initially co-managed by ECCC and DFO, but was administered by ECCC. In 2018-19, DFO assumed responsibility for administering Gs&Cs funding for aquatic species and aquatic stewardship projects on a regional basis. HSP was created with the goal to contribute to the recovery of endangered, threatened, and other species at risk by engaging Canadians from all walks of life in conservation actions to benefit wildlife.

Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk (AFSAR)

Established in 2004, AFSAR supports the development of Indigenous capacity to participate actively in the implementation of the Species at Risk Act. The program’s objectives are to conserve and recover species at risk and their habitats, and to support Indigenous organizations and communities as they continue developing the capacity to lead in the stewardship of species at risk.

Each of these Gs&Cs programs are distinct, however, program objectives overlap among all three, and in some cases expected results are exactly the same. Broadly speaking, the Gs&Cs programs are expected to contribute to ensuring that:

- Canada’s wildlife and habitat is conserved and protected

- Canada’s species at risk are recovered

- Indigenous Peoples are engaged in conservation efforts

Over the past five years, the use of Gs&Cs programs within DFO to achieve SAR objectives for aquatic species at risk has increased exponentially from $1.8 million in 2016-17 to $19.9 million in 2020-21. Since 2018-19, DFO assumed responsibility from ECCC for the aquatic component of HSP, as well as the $55M over five years to administer the CNFASAR as part of Canada’s Nature Legacy.

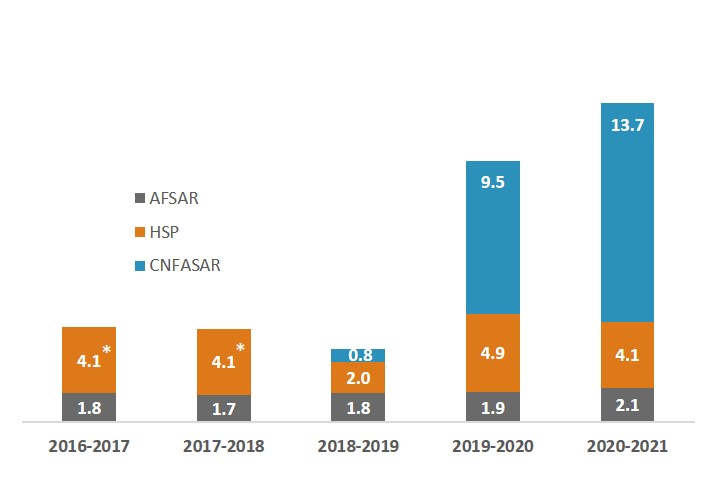

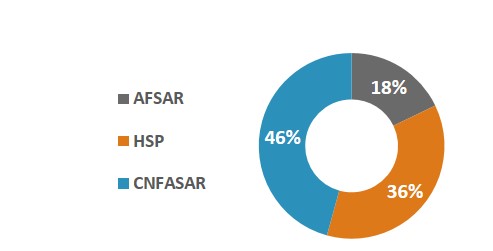

As shown in Figure 12, AFSAR funding has remained consistent throughout the evaluation period – approximately $2M is budgeted each year. Due to CNFASAR, DFO's Gs&Cs expenditures have increased since 2018-19.

As of March 2021, 350 contribution agreements to support the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk had been put in place under all three Gs&Cs programs, totaling $44.3 million over the evaluation period.

Figure 12 : Disbursement of expenditures for aquatic species at risk for the three Gs&Cs programs from 2016-17 to 2020-21, in millions

Description

The bar graph depicts the expenditures for each of the three Gs&Cs programs from 2016-17 to 2020-21 (in millions).

In 2016-17, AFSAR disbursed $1.8 million, HSP disbursed $4.1 million, and CNFSAR disbursed $0 million.

In 2017-18, AFSAR disbursed $1.7 million, HSP disbursed $4.1 million, and CNFSAR disbursed $0 million.

In 2018-19, AFSAR disbursed $1.8 million, HSP disbursed $2 million, and CNFSAR disbursed $0.8 million.

In 2019-20, AFSAR disbursed $1.9 million, HSP disbursed $4.9 million, and CNFSAR disbursed $9.5 million.

In 2020-21, AFSAR disbursed $2.1 million, HSP disbursed $4.1 million, and CNFSAR disbursed $13.7 million.

* These numbers represent ECCC expenditures for HSP’s aquatic component. For the first two years, ECCC and DFO shared administrative responsibilities for transfers of Gs&Cs funds to recipients under the HSP.

Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk (# of projects between 2016-17 and 2020-21)

- total: 177

- active: 98

- completed: 63

- cancelled: 7

- application received: 9

Habitat Stewardship Program (# of projects between 2018-19 and 2020-21)

- total: 124

- active: 103

- cancelled: 1

- application received: 20

Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (# of projects between 2018-19 and 2020-21)

- total: 57

- active: 57

- Source: Information provided by the Program.

Survey data show that Gs&Cs projects contributed to the expected results of the three programs:

75% Conserve and protect Canada’s wildlife

73% Recover Canadian species

33% Engage Indigenous people in conservation

Although not a direct objective for aquatic species at risk, interviewees indicated that the Gs&Cs programs also contribute a great deal to capacity building among recipient organizations as shown in Figure 14. In addition, the majority of survey respondents partnered with at least one other group or organization throughout the course of their project. This Gs&Cs funding goes beyond simply providing funding for a specific project, and also provides opportunities to increase collaboration more broadly.

Survey data show that funded projects contribute to all eligible activities. The majority of funded projects involve outreach and education; surveys, inventories, and monitoring; species and habitat threat abatement; and habitat improvement.

Figure 14 : Gs&Cs projects contribute to all eligible activities

Description

The bar graph depicts which eligible activities Gs&Cs projects are contributing to.

80% of projects contribute to Outreach and education.

68% of projects contribute to Surveys, inventories and monitoring.

62% of projects contribute to Species and habitat threat abatement.

58% of projects contribute to Habitat improvement.

43% of projects contribute to Conservation planning.

35% of projects contribute to Capacity building.

For more detailed information on the Gs&Cs projects and their recipients, please see Annex C

3.3.2 Contribution to the protection and recovery of Species at Risk

Gs&Cs programs achieve results for aquatic species at risk

Some highlights of the work being undertaken for aquatic species at risk over the evaluation period, as identified through a review of SARA Annual Reports,Footnote 10 include:

- efforts by Dalhousie University to raise larval Atlantic Whitefish (a species in danger of extinction) and captive-breed them

- outreach (including presentations, tours, customized conservation manuals, provision of seeds for cover crops) with farmers on conserving species at risk fish populations by reducing erosion and improving water quality

- strengthening of salmon governance for the Eastern Cape Breton Atlantic Salmon population through the work of the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources – monitoring activities, outreach and education activities

- creation of a children’s activity booklet about Great Lakes species at risk

“In our most recent project we have reached over 45,000 Canadians with aquatic SAR awareness messaging.”

– Survey respondent

“The collected information and gained knowledge will help conserve the species in the future.”

– Survey respondent

Survey respondents indicated that they believe their project is making/or will make a difference for aquatic species at risk to a moderate to great extent.

Interviewees indicated a similar rating (closer to a moderate extent) in the achievement of results for species at risk.

93% of recipients indicated that Gs&Cs programs contribute to protecting aquatic species at risk to a moderate or great extent.

92% of recipients indicated that their projects made a difference for aquatic species at risk to a moderate or great extent.

The majority of survey respondents (82%) indicated that they expect their project(s) will achieve its intended outcomes to a great extent, however not without challenges.

Sixty-seven percent of respondents indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic is a hindering factor to the success of recent and current projects, while 26% identified a lack of human resources and 23% identified a lack of financial resources as hindering factors.

Figure 15 : Factors that hindered recipients’ ability to achieve project outcomes

Description

The figure depicts the factors that hindered recipients’ ability to achieve project outcomes.

67% identified COVID-19 pandemic.

26% identified a Lack of human resources.

23% identified a Lack of financial resources.

21% identified a Lack of interest from partners.

12% identified Technological challenges.

7% identified Geographic location.

7% identified Weather conditions.

When recipients were asked to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their projects, it was mostly to a limited or moderate extent.

Figure 16 : Impact of COVID-19 on project delivery

Description

The bar graph depicts the extent to which recipients found that COVID-19 impacted their projects. 7% selected “not at all”, 40% selected “to a limited extent”, 38% selected “to a moderate extent”, and 16% selected “to a great extent”.

Interviewees suggested that the Gs&Cs programs are limited in their ability to achieve results (particularly for AFSAR, but also HSP) by the availability of funding – not only by the amount of funding that is available to be dispersed, but also by the uncertainty of the availability of funding over time.

The nature of species at risk protection and recovery is that it takes many years for noticeable changes to be made for a species given the complexity of the work. Having sustained funding available, such as Gs&Cs multi-year agreements, may be an important aspect to the work being done for aquatic species at risk. While CNFASAR projects are signed as multi-year projects* given that they are often large scale projects, this is the case for only half of HSP projects and 29% of AFSAR projects.

*Except for the first year of funding, which is single year.

Figure 17 : Type of contribution agreement in place for each Gs&Cs program, 2016-17 to 2020-21

Description

The figure depicts a pie chart for each of the three G&C programs. Each pie chart depicts the type of contribution agreement in place as a percentage of the total projects between 2016-17 to 2020-21.

For AFSAR, 29% of projects were multi-year and 71% of projects were single-year.

For HSP, 50% of projects were multi-year, 40% of projects were single-year, and 10% of projects have no data.

For CNFASAR, 86% of projects were multi-year and 14% of projects were single-year.

Source: Administrative data

As SARP moves towards new approaches, such as multi-species and eco-systems-based approaches, the availability of sustained, multi-year funding may help support recipients to undertake more complex projects.

3.3.3 Barriers to program participation

GBA+ inclusivity and accessibility

DFO may be missing out on opportunities to fund certain projects due to barriers faced by potential applicants. Based on survey data, recipients indicated some barriers to access Gs&Cs programs.

Figure 18: Barriers to accessing Gs&Cs funding

Description

The bar graph depicts the barriers to accessing Gs&Cs funding that recipients identified.

30% of recipients reported that Organizational size and maturity was a barrier to accessing funding.

19% of recipients reported that Prior relationship to DFO was a barrier to accessing funding.

17% of recipients reported that Location was a barrier to accessing funding.

15% of recipients reported that Language was a barrier to accessing funding.

The majority of survey respondents identified themselves as scientists or researchers, in mid-late career, with English as their first official language.

When considering organizational size and maturity, survey respondents indicated that smaller organizations may not have the capacity to engage in the detailed, rigorous application (and then reporting) process, nor the resources to undertake larger-scale projects. These Gs&Cs programs were not designed for only large, high capacity organizations to receive funding, however organizational capacity would be an asset in order to apply. Interviewees supported this finding, noting that the application process is onerous for smaller organizations who are requesting less funding, particularly if they are unsuccessful during the application phase.

Other issues identified through the interviews and/or survey include:

- a need for tools and templates to support organizations in completing strong applications

- support and guidance for costing out projects

- the majority of respondents (79%) had been informed of the funding opportunity by way of an official notification from DFO, however a large number (64%) had found out through word-of-mouth.Footnote 11 This creates a potential barrier to accessing funding opportunities for organizations that have not previously received funding from DFO, and suggests room for improvement in terms dissemination of information on these programs

3.3.4 Level of satisfaction of recipients

Figure 19 : Survey responses regarding Gs&Cs program processesFootnote 12

Description

The figure depicts the survey responses regarding Gs&Cs program processes.

In response to the question, “It is easy to find information on these Gs&Cs program(s)”, 76% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “Information provided on these Gs&Cs program(s) is clear”, 77% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “There was sufficient time between becoming aware of the funding opportunity and the application deadline”, 71% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The application process is easy to follow”, 64% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “Overall, I received helpful feedback from DFO”, 88% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “I received clear information regarding eligible activities and expenses”, 94% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The templates provided were easy to use (e.g., reporting templates)”, 61% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

In response to the question, “The reporting requirements were reasonable”, 71% of recipients selected either “to a moderate” or “to a great extent”.

The administration of the Gs&Cs programs and support provided by DFO staff were generally perceived quite positively by survey respondents. Recipients were especially pleased with the information they received regarding eligible activities and expenses (94%) and thought that DFO provided helpful feedback to them (88%).

“I have been incredibly grateful for the tremendous support we have had from our partners in both ECCC (previous years) and DFO.”

– Survey respondent

“The reporting requirements are quite onerous for smaller organizations. It is substantially more time and effort than with any other funding provider.”

– Survey respondent

As DFO has only been administering HSP and CNFASAR for a few years, there are a few areas where improvements could be made. Recipients encountered some challenges in their interactions with DFO related to:

- delays in DFO’s review and approval of contribution agreements (81%)

- timely transfer of funds from DFO (57%)

- requirements for reporting were seen as onerous (29%), particularly for smaller organizations

3.3.5 Relevance of funding

More than half of the projects would not have taken place without DFO funding.

Fifty-six percent of survey respondents indicated that their projects would not have taken place in the absence of this funding.

- the same respondents emphasized that their projects were dependent on funding received from DFO

One third of the projects would have taken place but to a lesser extent

Thirty-five percent of survey respondents indicated their projects would have taken place, but to a lesser extent:

- 85% indicated that funding allowed for expanded and fulsome projects

- 23% indicated that funding allowed them to work with more partners

- 23% indicated that they accomplished more habitat restoration because of the funding

Other funding sources are dependent on DFO funding (46%)

Funding from other sources is only provided as “matched dollars”, once support from DFO has been received.

Other funding sources are limited (38%)

There are other funding sources, but they tend to be limited and less accessible due to the large number of applicants.

Other funding sources are less flexible (31%)

Alternative sources of funding may be time sensitive and not cover certain activities (e.g., monitoring, staff pay).

“AFSAR is a foundational program.”

– DFO Staff

“CNFASAR funding has been critical to advancing our project and building local capacity.”

– Survey respondent

3.4 Alternative Legislative Tools to Modernize SARA Delivery

There are multiple pieces of legislation that lay out the department’s authorities and responsibilities when it comes to Canada’s fisheries and oceans – namely the Fisheries Act, the Oceans Act, and the Species at Risk Act.

While the legislative tools available within SARA are the strongest in terms of providing protections to species at risk, there is a common view among interviewees that there are some limitations to this Act, which can sometimes discourage its use for certain species.

- SARA is considered by some to be too restrictive – it is “all or nothing” and does not allow for nuance in conserving species, which makes it a tool of last resort due to the implications of listing species

- SARA is extremely prescriptive and complex in its requirements and timelines, and these requirements can be difficult to meet. Interviewees expressed that more flexibility in the Act would be positive

Some interviewees expressed that revisions to SARA may be necessary to optimize its usefulness and bring it into alignment with other government priorities (for example, Indigenous reconciliation). It is worth noting that the Mandate Letter for the Minister of ECCC, requires that the Minister “continue to work to protect biodiversity and species at risk, while engaging with provinces, territories, Indigenous communities, scientists, industry and other stakeholders to evaluate the effectiveness of the existing SARAand assess the need for modernization.”

Key legislative tools that could be used more frequently, or more effectively, to protect and recover Aquatic Species at Risk

Species at Risk Act

- Section 11 – Conservation Agreements

- Section 32 – Killing, Harming, etc. Listed Wildlife Species

- Sections 73, 74 & 83 – Permits, Exemptions, and Exceptions

Fisheries Act

- Section 6 – Fish stocks (particularly stock rebuilding provisions)

- Section 34 to 36 – Fish and Fish Habitat Protection and Pollution Prevention

- Section 35.2 – Ecologically Significant Areas

Oceans Act

- Section 35 – Designation of Marine Protected Areas

Finding: In some cases, outcomes for aquatic species at risk could be more effectively and efficiently facilitated through the use of legislative tools other than SARA.

As part of its efforts to modernize the delivery of SARA, SARP has been exploring alternative approaches, including increased use of tools available in other legislation, such as those in the Fisheries Act and the Oceans Act, in order to protect and recover species at risk. Interviewees agreed that these tools are viable potential options to work around the limitations of SARA in some circumstances. In particular, the Fisheries Act provides flexibility to minimize socio-economic impacts and to exempt low-risk activities.

A number of useful provisions from other legislation and supporting policy tools were suggested by interviewees for the conservation of species at risk. The list of options and their descriptions is included in Annex D. Options identified as having the most potential include:

Under the Fisheries Act

- Section 6 – Fish stocks (particularly stock rebuilding provisions)

- Section 34 to 36 – Fish and Fish Habitat Protection and Pollution Prevention

- Section 35.2 – Ecologically significant areas

Under the Oceans Act

- Section 35 – Designation of Marine Protected Areas

Steelhead trout

- Steelhead trout have been in significant decline. The Thompson and Chilcotin Steelhead runs in particular have reached critically low levels

- It was determined that an emergency listing would produce suboptimal ecological, social and economic outcomes relative to a comprehensive, long-term collaborative action plan with the province of British Columbia (BC).

- in the absence of listing under SARA, Steelhead will continue to be managed for conservation under the Fisheries Act, as well as under provincial legislation

- DFO and the province of BC released a Steelhead Action Plan outlining measures to protect these populations, including closing the recreational fisheries in the Thompson and Chilcotin watersheds and putting in place rolling closures for commercial salmon fisheries, as well as improving freshwater conditions through improved watershed management and investments in habitat protection and restoration.

Considerations for using tools under other legislation:

Key informants indicated that there is a lack of strategic direction/guidance on the use of other legislative tools and the ways in which the different acts intersect and overlap. Specific areas mentioned for which increased guidance is needed include:

- when it is appropriate to use other legislation in place of SARA

- how to create buy-in for using tools under the Fisheries Act, as they can affect the income of fishers and businesses (already identified as a challenge when using the Fisheries Act)

- how to align COSEWIC’s approach to assessing the level of risk with related assessments for the use of other legislative tools (e.g., the limit reference point for determining whether a fish stock is healthy may not align with COSEWIC’s criteria to determine whether a population is at risk).

- when to use Ecologically Significant Areas in the Fisheries Act vs Marine Protected Areas in the Oceans Act

Authorities for using different provisions are complex and spread across programs in the department. For example, the responsibility for ensuring safe fishing rests with Fisheries Management, but responsibility for habitat rests with Fish and Fish Habitat Protection Program. There is a need for better integration between programs with responsibilities for at-risk species and clear guidance on the use of other tools to protect species to help manage the increased complexity of using alternative legislative tools.

SARP’s current efforts to collaborate across the department to modernize the delivery of SARA present a timely opportunity to work with partners on the clarification of roles and responsibilities, and on the development of guidance regarding the use of alternative legislative tools as they pertain to species at risk and their intersection with SARA.

3.5 Utilization of tools within SARA

Interviewees indicated that there are situations in which SARA is a more appropriate option, particularly for species that are not high profile and for species in dire situations that require immediate action, as provisions from other legislation take more time to start making a difference. The provisions in the Fisheries Act are more preventative, whereas those in SARA are more corrective.

Interviewees indicated that there are tools within SARA that could be used more frequently or more effectively than they currently are to improve conservation efforts. However, increased guidance on their use is needed and, in some cases, potential issues related to jurisdictional authorities would need to be addressed.

Section 11 Conservation agreements

Conservation agreements are useful in formalizing roles and responsibilities and commitments of partners to conserving at risk species, and in increasing the transparency of DFO’s work and that of its partners.

Section 32 Killing, harming, etc. listed wildlife species

This provision can provide more encompassing options to protect aquatic species than the similar provision in the Fisheries Act, which only prohibits death of fish. Section 32 of SARA can prohibit against levels of harm and harassment which can have consequential effects on species that are not necessarily related to death.

Sections 73, 74 and 83 Permits, exemptions, and exceptions

Increased usage of permits, exemptions and exceptions could enable increased use of SARA listings to protect species that are implicated in fisheries, which currently tend to be avoided due to the socio-economic consequences of halting fishery and other activities.

4.0 Conclusions and recommendations

4.1 Conclusions

Overall, SARP is working toward the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk, but not without challenges. The complexity of SARA, the number and diversity of partners across the department needed to deliver this uniquely decentralized program, make for a complex and challenging operating environment. To achieve results, SARP has worked extensively with multiple partners, both internally and externally, to undertake cross-cutting activities that contribute to the protection and recovery of aquatic species at risk. Nevertheless, there are opportunities to improve effectiveness and efficiency through greater delineation of roles and responsibilities within the department, and increased governance and accountability for species at risk activities. These improvements will be even more important as the program continues to move towards the increased use of ecosystem-based approaches and potentially greater reliance on alternative legislative tools, recognizing that there are limitations with all legislative tools.

4.2 Recommendations

Recommendation 1: It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Aquatic Ecosystems, with the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Fisheries and Harbours Management, the Assistant Deputy Minister Ecosystems and Oceans Science, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy and Regional Directors General in each region conduct a review of current governance structures for aquatic species at risk activities; identify a new or existing executive-level forum for holistic and targeted species at risk-related discussions and decision-making; and clearly define roles and responsibilities for all levels of management responsible for the delivery of aquatic species at risk activities.

Rationale: There is a need for a more holistic decision-making forum to effectively manage the complexity of delivering aquatic species at risk activities. While several species at risk-related committees and working groups are currently in place, existing fora do not include the full range of programs that can provide relevant input for species at risk decision-making and activities. The current governance structures do not provide adequate direction and oversight on the complex delivery of aquatic species at risk activities, and there is a need to define roles and responsibilities for all levels of management responsible for the delivery of aquatic species at risk activities.

Recommendation 2: It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Aquatic Ecosystems, provide more specific guidance for the structure and contents of recovery documents, and for the associated reporting on results, to more effectively support the implementation of recovery actions and assessment of progress.

Rationale: The Program produces recovery documents (Recovery Strategies, Action Plans, and Management Plans) that provide large amounts of useful information on aquatic species at risk. However, there is a need for greater precision regarding the elements that guide the implementation of recovery actions and reporting on results and progress. Where feasible, clear and specific identification of parties responsible for recovery actions, timelines for these actions, and performance measures and targets to measure success could improve the effectiveness of recovery documents as a key tool.

Recommendation 3: It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Aquatic Ecosystems, with the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Fisheries and Harbours Management, the Assistant Deputy Minister Ecosystems and Oceans Science, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy, the Chief Financial Officer and Regional Directors General in each region reassess how accountability for species at risk funding to partner sectors is documented, with a view to ensuring a greater level of accountability for this funding and associated deliverables, for example, through standardized, consistent use of Service Level Agreements or the regional delegation feature in the iResults system.

Rationale: A large portion (52%) of SARP funding is distributed to other DFO sectors. The current internal funding distribution mechanisms in place in most regions make it difficult to validate that this funding is actually used solely for aquatic species at risk work. Accountability for species at risk deliverables resides with SARP, however the program has limited ability to exert influence over the prioritization of species at risk activities which compete with other priorities in partner sectors.

Recommendation 4: It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Aquatic Ecosystems, with the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Fisheries and Harbours Management, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy and Regional Directors General in each region as appropriate, explore options for leveraging alternative legislative tools, such as the Fisheries Act and Oceans Act, to protect and recover species at risk; and begin to implement, as appropriate, feasible options.