Habitat Highlight: Fish, floods and habitat connectivity in the Lower Fraser

This Habitat Highlight explores the threats of climate change, habitat modification, and habitat degradation and tells the story of why it is important to preserve and restore connection between fish spawning and rearing habitat in the lower parts of the Fraser River and its estuary. Fish need safeguarding, as well as safe passage to search for food, shelter, and spawning opportunities.

Some of the infrastructure built adjacent to the Lower Fraser River over the past century has blocked or degraded aquatic habitat. Flood infrastructure has played a large role in this. Salmon and other fish depend on access to these habitats to complete their lifecycles and maintain healthy populations. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is working to conserve and restore habitat connectivity by providing funding and supporting the assessment and replacement of barriers to fish passage with fish-friendly, nature-based infrastructure in the Lower Fraser.

This content is also available in an interactive format (StoryMap: Fish, Floods, and Habitat Connectivity in the Lower Fraser).

On this page

- A region with diverse habitats

- Species in the spotlight

- Challenges and threats

- Working with others to protect fish and fish habitat in the Lower Fraser

- Additional resources

- References

A region with diverse habitats

The mighty Fraser River

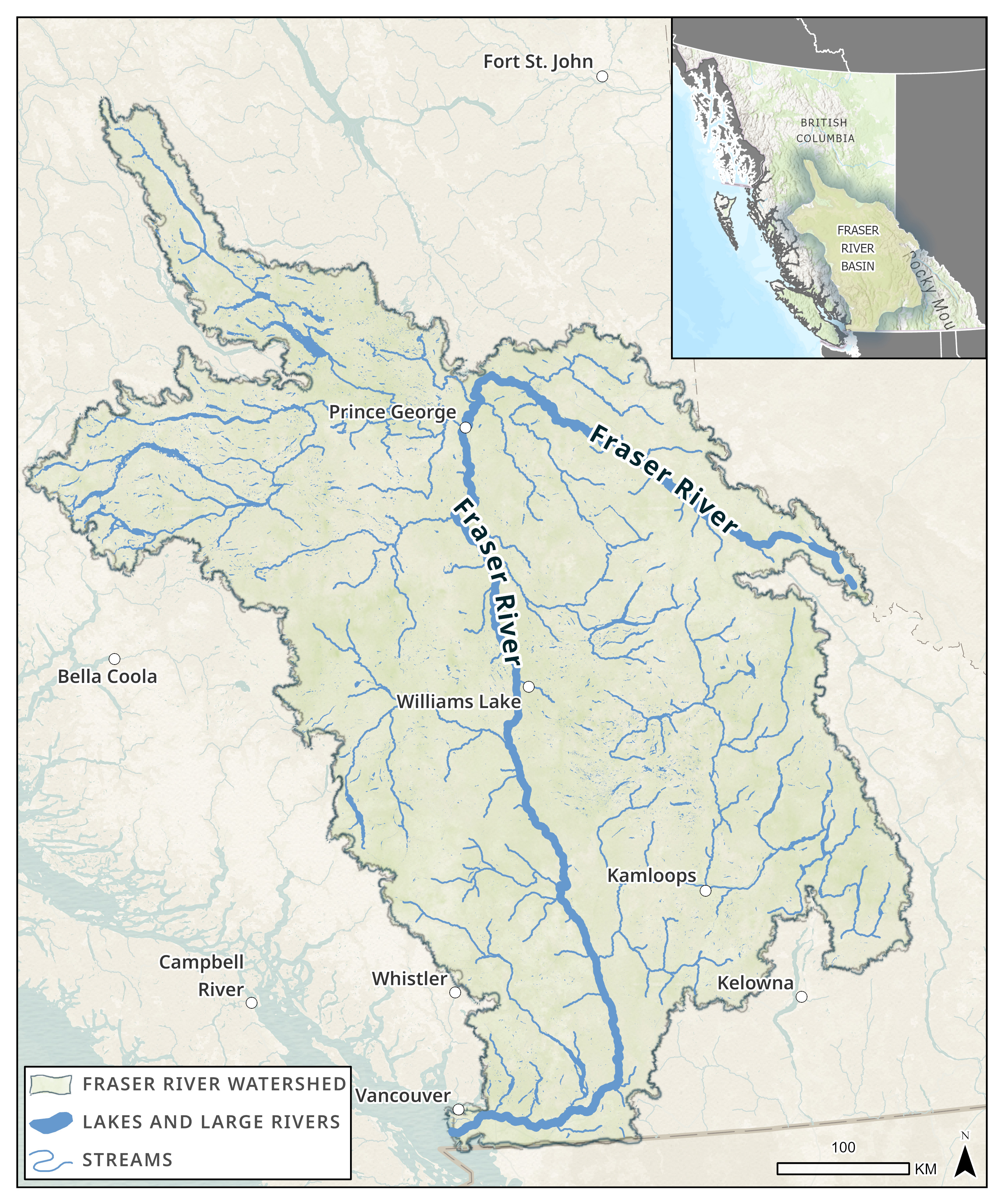

The Fraser River is one of the mightiest rivers in Canada, and the longest in British Columbia (BC). It begins at the glaciers of Mount Robson and flows 1,400 km southwest to the Salish Sea in the Pacific Ocean. The Fraser River Basin has a watershed area of over 220,000 square kilometres. Nearly a quarter of BC's fresh water drains through the Fraser River watershedFootnote 1. Figure 2 gives an idea of the immense size of this watershed. This productive ecosystem has been vitally important to Indigenous communities for food, social, and ceremonial purposes, and to BC's recreational and commercial fisheries.

Figure 2 - Data sources for base map

Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Source: Map developed by DFO using data from DataBC.

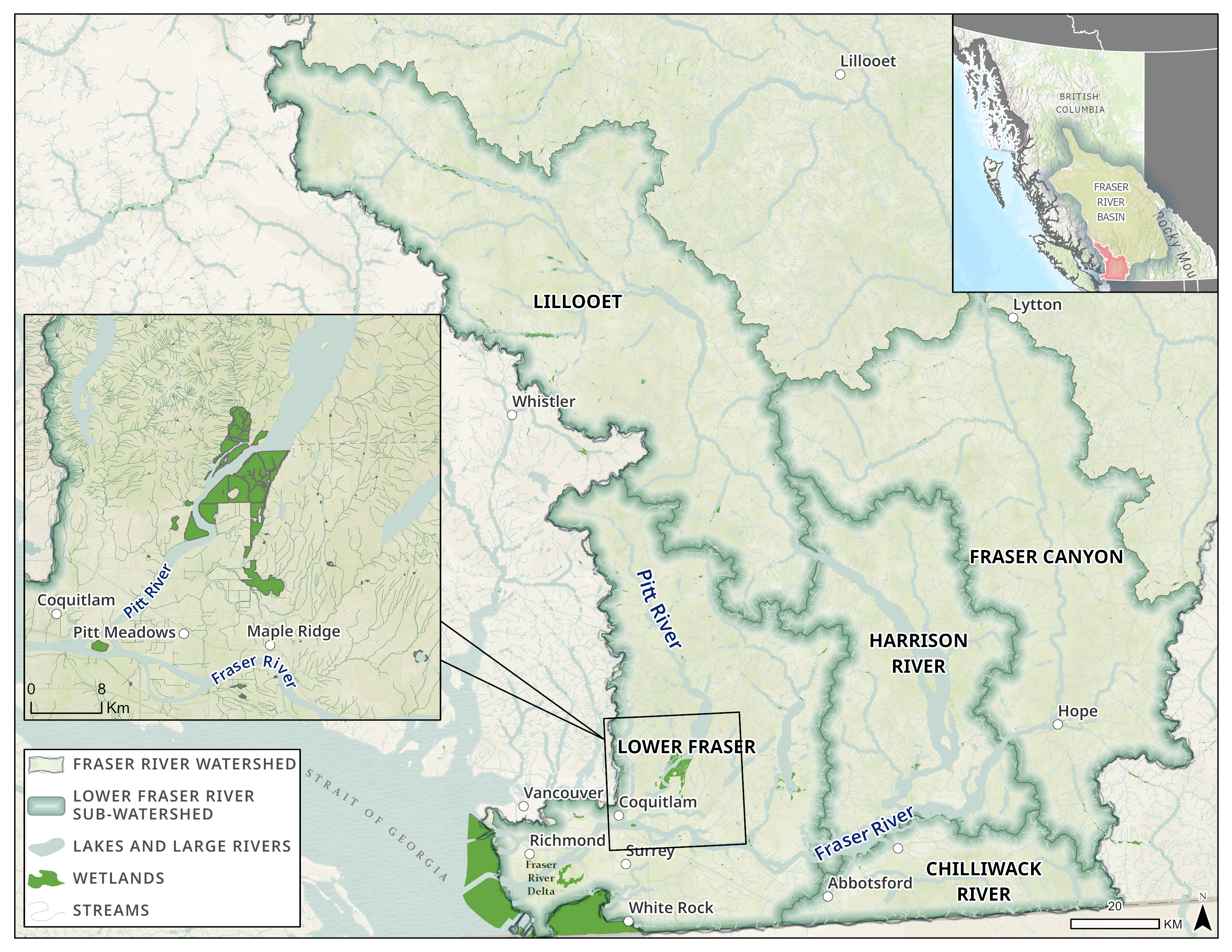

A closer look at the Lower Fraser watersheds

The Lower Fraser Basin is one of the richest areas for biodiversity and fish habitat in Canada. The Lower Fraser River begins north of the District of Hope in the Fraser Canyon. The canyon acts as a physical marker for changes in the hydrology and fish communities of the Fraser RiverFootnote 2. The river flows fast and steep through the mountain ranges, picking up nutrients, sand, and gravel along the way. The sediment transported from the mountains is deposited in the Lower Fraser creating gravel or sand bars, which can serve as healthy spawning and rearing habitat for salmon and other fish species. The incline flattens at Hope, and the river's path widens with braided channels extending along the gravel reach of the lower Fraser River, also known as the “Heart of the Fraser”, to approximately the confluence with the Sumas River. Downstream of Sumas River, the Fraser River is dominated by smaller sand and silt particles, and habitats here fall within the tidal influence of the Salish Sea. Fish in the Lower Fraser and its estuary benefit from the complex network of different aquatic habitats with small streams, riverbeds and banks, lakes, wetlands, and floodplains. The estuary, where fresh water from the Fraser River mixes with tidal marine waters from the Salish Sea, provides highly productive habitat for many fishFootnote 3.

The Fraser River measures 180 km from Yale, BC to the ocean, but its historical network of tributaries, side channels, and streams provided over 2,000 km in linear aquatic habitatFootnote 4. This habitat network is rendered less accessible for fish because of infrastructure developments that may, for example, impact flow or fish passage either directly or indirectly.

Figure 3 - Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Source: Map developed by DFO using data from DataBC.

The Lower Fraser Basin is composed of several sub-watersheds and includes water draining from the Harrison River, Sumas River, Stave River, Pitt River, Coquitlam River, and Brunette River watersheds, among others.

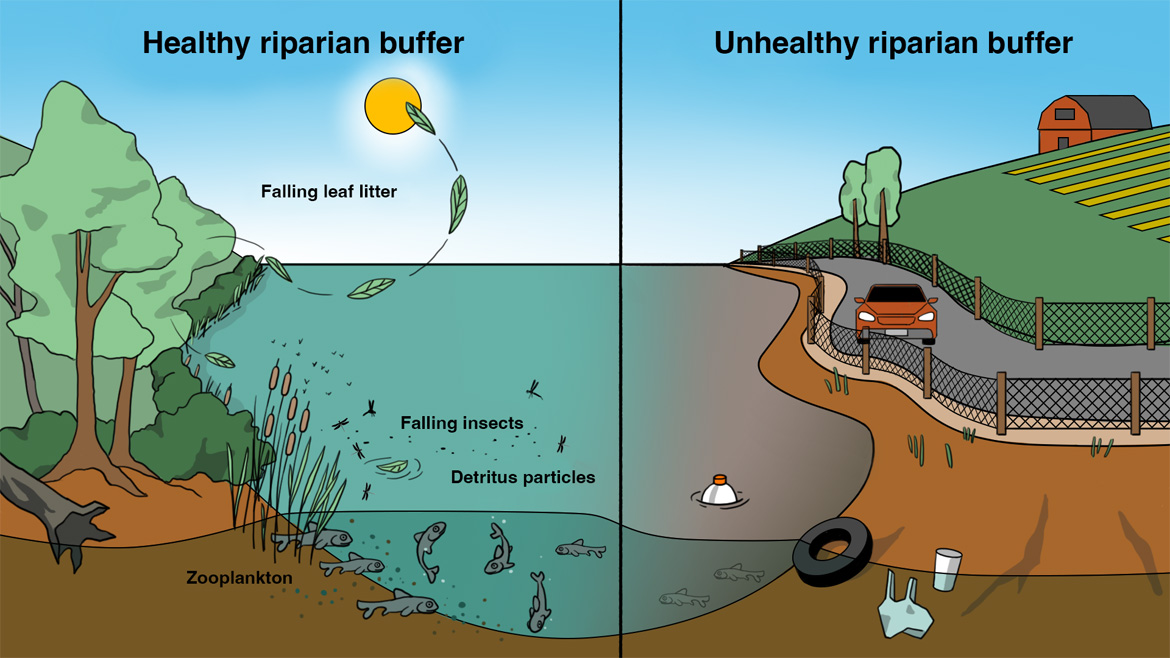

Diverse aquatic habitat

The food and environmental needs of fish are dynamic across species and life stages. The diversity of food sources and habitats in the Lower Fraser is one of the reasons it has such rich aquatic biodiversity. Fish in the Lower Fraser can migrate to habitats that suit their varying needs that change between seasons and life stages, as shown below.

Large rivers: Deep and wide river channels are excellent habitat for foraging fish and large predatory fish. These major rivers also act as highways that enable all fish in the watershed to migrate to different habitats as the survival needs of fish change on a daily, seasonal, or lifecycle basis, whether it be to lakes, to side channels and smaller streams, wetlands, or the ocean.

Streams and side channels: If rivers act as fish highways, then the tributary streams and side channels act as the streets and sidewalks of the watershed. A healthy stream provides niche habitat with woody debris and vegetation for small fish to hide, and plenty of invertebrates to eat. While individually small, the combined linear aquatic habitat provided by these streams and side channels is much greater than the length of the Fraser River.

Lakes: The Lower Fraser network contains lakes that are essential for the ecosystem because they provide habitat for animals and plants that need still water. Like streams and side channels, a healthy lake has nearshore vegetation habitat that provides young fish refuge from larger predators. Many fish species depend on access to lakes and ponds for spawning, juvenile rearing, and food sources.

Wetlands and estuaries: The greatest of the Lower Fraser wetlands occurs in the Fraser River Delta. This world-renowned wetland complex is part of one of the most biologically productive estuaries in Canada. It includes Burns Bog, Sturgeon Banks, Roberts Banks, South Arm Marshes, and Boundary Bay. Every wild salmon born in the Fraser River network will pass through the estuary and spend days or months in this estuary as out-migrating juveniles to eat, rest, acclimatize to salt water, and grow strong enough for life in the open ocean (Footnote 5,Footnote 6). Unfortunately, more than half of the historical Fraser River estuary wetlands have been diked, drained, or filled for land developmentFootnote 7.

Source: Developed by Kerel Alaas for DFO.

The Fraser River is a rich aquatic ecosystem with over 50 species of freshwater fishFootnote 8. Over 30 marine or saltwater tolerant species occupy the Fraser River estuaryFootnote 9. The Lower Fraser contains more fish species than any other part of the Fraser River BasinFootnote 10.

Species in the spotlight

Wild Pacific salmon

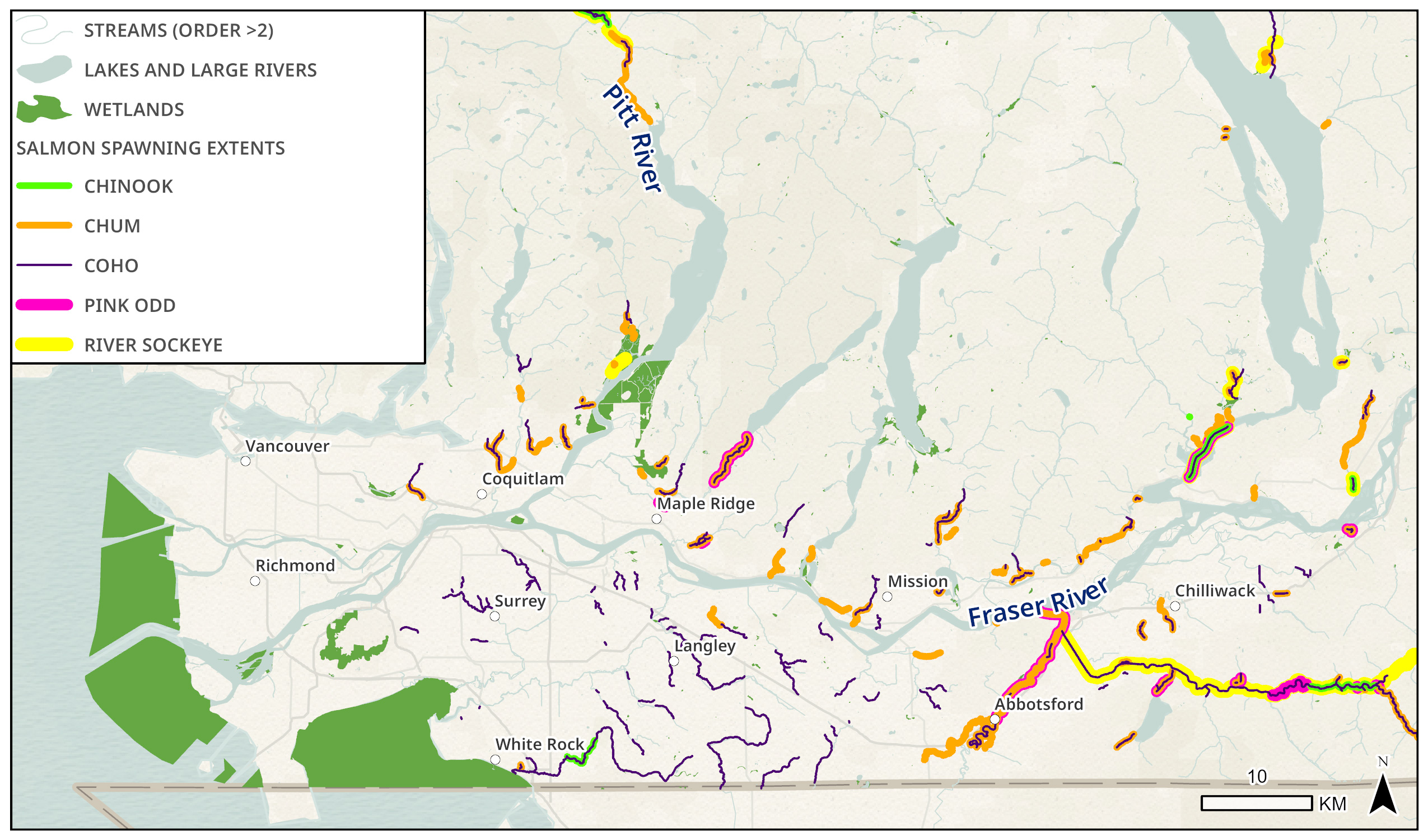

Figure 7 - Data sources

Data sources for Pacific salmon spawning locations

Data assembled by the Pacific Salmon Foundation's Salmon Watersheds Program for the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance. Source data comes from DataBC's BC Historical Fish Distribution - Zones (50,000) (line locations) and Known BC Fish Observations and BC Fish Distributions (point locations), and supplemental locations contributed by regional experts during technical working group meetings facilitated by the Salmon Watersheds Program.

Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Map developed by DFO with data from the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

Note: for an interactive version of this map please visit the Fish, Floods, and Habitat Connectivity in the Lower Fraser River StoryMap.

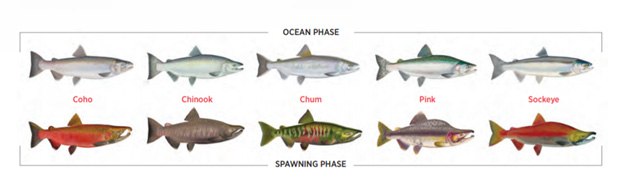

Pacific salmon are iconic to Canadians. The Fraser River is known as the world's greatest single producer of Pacific salmonFootnote 11. It is home to populations of all species of Pacific salmon such as sockeye, Chinook, coho, chum, and pink salmon, as well as steelhead/rainbow and cutthroat trout. These species have been vitally important to Indigenous communities for food, social, and ceremonial purposes since time immemorial. Salmon have long contributed to the overall cultural and economic fabric of Canada's west coast and are important to recreational and commercial fisheries. Pacific salmon follow a lifecycle pattern of spawning and rearing in freshwater before eventually migrating as juveniles out to the ocean. DFO has resources devoted to studying and managing the Lower Fraser habitat network because of the area's importance in supporting the spawning, migration, rearing, and over-wintering of Pacific salmon species (Footnote 12,Footnote 13). Figure 8 depicts recent spawning locations of these species within the Lower Fraser.

Resources

- The 5 Pacific salmon managed by DFO

- State of the Canadian Pacific salmon: Responses to changing climate and habitats

- Wild Salmon Policy

- Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative

- The importance of the Fraser Estuary for Chinook salmon

Sturgeon and eulachon

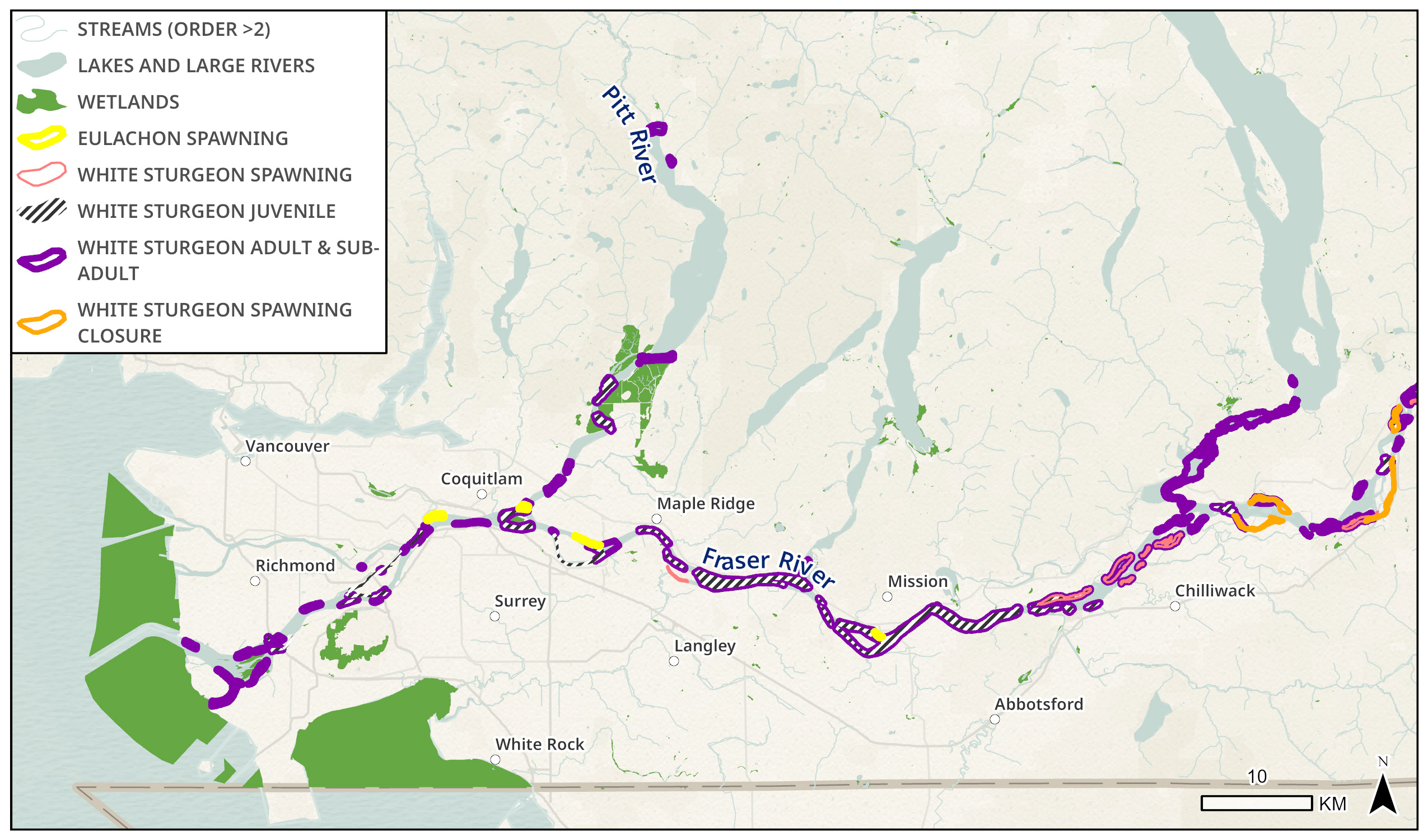

The Lower Fraser is home to much more than salmon. Nearly half of the DFO Pacific Region's freshwater aquatic species at risk are found in the Fraser River along with many species of traditional and cultural importanceFootnote 14. Figure 9 shows important habitat of two other significant fish species in the Lower Fraser: white sturgeon and eulachon.

Figure 9 - Data sources

Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Map developed by DFO with data from DFO and DataBC.

Note: for an interactive version of this map please visit the Fish, Floods, and Habitat Connectivity in the Lower Fraser River StoryMap.

White sturgeon are famous for their dinosaur-like appearance with distinct rows of diamond-shaped bony projections on the body. They have long been an important cultural and food resource for Indigenous peoples. While white sturgeon may travel hundreds of kilometres in fresh water and marine habitats along the Pacific coast, they are known to only spawn in three major river systems, one of which is the Fraser River. They can live to be over 60 years old, reaching up to 6 m and 600 kg making them the largest freshwater fish in Canada. They are typically bottom feeders and feed on fish, crustaceans, mollusks, worms, and plant material. The Lower Fraser contains a population of white sturgeon that has been assessed as “Threatened” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

Eulachon are an ecologically significant forage fish species and are important to coastal Indigenous peoples for food and cultural purposes. Eulachon are anadromous; however, they spend almost all of their life in the ocean except for spawning. Eulachon spawning is limited to the lower reaches of only a few rivers in BC. The Lower Fraser River is the spawning ground to a population of eulachon, which are an important part of the diet for the Lower Fraser River population of white sturgeon, as well as sea lions, harbour seals, eagles, and other predators. The Fraser River eulachon spawning season typically peaks in April and May. Once hatched, eulachon larvae are quickly flushed out to the estuary and coastal ocean. They return three years later as adults from the ocean to spawn. Spawning rivers in BC have been experiencing low eulachon population levels over the past two decades, and the Fraser River population has been assessed as “Endangered” by COSEWIC.

Resources

- DFO-funded projects for species at risk in the Fraser Watershed priority area

- Middle and Lower Fraser white sturgeon threats and recovery strategy

- Fraser River eulachon 2022: Integrated fisheries management plan summary

Challenges and threats

Although salmon, sturgeon, and eulachon are vastly different in terms of size, diet, and habitat needs in the Lower Fraser, they share several threats in common: habitat degradation, habitat fragmentation, and land alteration within their watersheds. We explore and define some of these threats more in the paragraphs below.

Populations and borders

Figure 12 - Text version and data sources

| Boundary name | Boundary type |

|---|---|

| Abbotsford | Municipal |

| Anmore | Municipal |

| Belcarra | Municipal |

| Burnaby | Municipal |

| Chilliwack | Municipal |

| Coquitlam | Municipal |

| Delta | Municipal |

| Harrison Hot Springs | Municipal |

| Hope | Municipal |

| Kent | Municipal |

| Langley - City | Municipal |

| Langley - District | Municipal |

| Lions Bay | Municipal |

| Maple Ridge | Municipal |

| Mission | Municipal |

| New Westminster | Municipal |

| North Vancouver - City | Municipal |

| North Vancouver - District | Municipal |

| Pitt Meadows | Municipal |

| Port Coquitlam | Municipal |

| Port Moody | Municipal |

| Richmond | Municipal |

| Surrey | Municipal |

| Vancouver | Municipal |

| West Vancouver | Municipal |

| White Rock | Municipal |

| Aitchelitch 9 | Reserve Land |

| Aylechootlook 5 | Reserve Land |

| Barnston Island 3 | Reserve Land |

| Burrard Inlet 3 | Reserve Land |

| Capilano 5 | Reserve Land |

| Chawathil 4 | Reserve Land |

| Cheam 1 | Reserve Land |

| Chehalis 5 | Reserve Land |

| Chehalis 6 | Reserve Land |

| Coquitlam 1 | Reserve Land |

| Coquitlam 2 | Reserve Land |

| Defence Island 28 | Reserve Land |

| Grass 15 | Reserve Land |

| Graveyard 5 | Reserve Land |

| Holachten 8 | Reserve Land |

| Inlailawatash 4 | Reserve Land |

| Inlailawatash 4a | Reserve Land |

| Katzie 1 | Reserve Land |

| Katzie 2 | Reserve Land |

| Kitsilano 6 | Reserve Land |

| Kwawkwawapilt 6 | Reserve Land |

| Kwum Kwum | Reserve Land |

| Lackaway 2 | Reserve Land |

| Lakahahmen 11 | Reserve Land |

| Lakway Cemetery 3 | Reserve Land |

| Langley 2 | Reserve Land |

| Langley 3 | Reserve Land |

| Langley 4 | Reserve Land |

| Langley 5 | Reserve Land |

| Lukseetsissum 9 | Reserve Land |

| Matsqui 4 | Reserve Land |

| Matsqui Main 2 | Reserve Land |

| Mcmillan Island 6 | Reserve Land |

| Mission 1 | Reserve Land |

| Musqueam 2 | Reserve Land |

| Musqueam 4 | Reserve Land |

| Ohamil 1 | Reserve Land |

| Papekwatchin 4 | Reserve Land |

| Pekw'xe:yles (Peckquaylis) Indian Reserve | Reserve Land |

| Peters 1 | Reserve Land |

| Peters 1a | Reserve Land |

| Peters 2 | Reserve Land |

| Pitt Lake 4 | Reserve Land |

| Popkum 1 | Reserve Land |

| Popkum 2 | Reserve Land |

| Ruby Creek 2 | Reserve Land |

| Sahhacum 1 | Reserve Land |

| Schelowat 1 | Reserve Land |

| Schkam 2 | Reserve Land |

| Scowlitz 1 | Reserve Land |

| Sea Island 3 | Reserve Land |

| Seabird Island | Reserve Land |

| Semiahmoo | Reserve Land |

| Seymour Creek 2 | Reserve Land |

| Skawahlook 1 | Reserve Land |

| Skowkale 10 | Reserve Land |

| Skowkale 11 | Reserve Land |

| Skumalasph 16 | Reserve Land |

| Skwah 4 | Reserve Land |

| Skwahla 2 | Reserve Land |

| Skwali 3 | Reserve Land |

| Skway 5 | Reserve Land |

| Skweahm 10 | Reserve Land |

| Soowahlie 14 | Reserve Land |

| Squawkum Creek 3 | Reserve Land |

| Squiaala 7 | Reserve Land |

| Squiaala 8 | Reserve Land |

| Stawamus 24 | Reserve Land |

| Sumas Cemetery 12 | Reserve Land |

| Three Islands 3 | Reserve Land |

| Tseatah 2 | Reserve Land |

| Tzeachten 13 | Reserve Land |

| Upper Sumas 6 | Reserve Land |

| Wahleach Island 2 | Reserve Land |

| Whonnock 1 | Reserve Land |

| Williams 2 | Reserve Land |

| Yaalstrick 1 | Reserve Land |

| Yakweakwioose 12 | Reserve Land |

| Zaitscullachan 9 | Reserve Land |

| Brackendale Eagles Park | Provincial Park |

| Bridal Veil Falls Park | Provincial Park |

| Chilliwack River Park | Provincial Park |

| Cultus Lake Park | Provincial Park |

| Cypress Park | Provincial Park |

| Davis Lake Park | Provincial Park |

| Ferry Island Park | Provincial Park |

| F.H. Barber Park | Provincial Park |

| Fraser River Ecological Reserve | Provincial Park |

| Golden Ears Park | Provincial Park |

| Halkett Bay Marine Park | Provincial Park |

| Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve | Provincial Park |

| Kilby Park | Provincial Park |

| Liumchen Ecological Reserve | Provincial Park |

| Mount Seymour Park | Provincial Park |

| Murrin Park | Provincial Park |

| Peace Arch Park | Provincial Park |

| Pinecone Burke Park | Provincial Park |

| Pitt Polder Ecological Reserve | Provincial Park |

| Porteau Cove Park | Provincial Park |

| Rolley Lake Park | Provincial Park |

| Sasquatch Park | Provincial Park |

| Say Nuth Khaw Yum Park [a.k.a. Indian Arm Park] | Provincial Park |

| Shannon Falls Park | Provincial Park |

| Stawamus Chief Park | Provincial Park |

| Stawamus Chief Protected Area | Provincial Park |

| Sxotsaqel / Chilliwack Lake Park | Provincial Park |

Data sources for base map

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Map developed by DFO with data from DataBC.

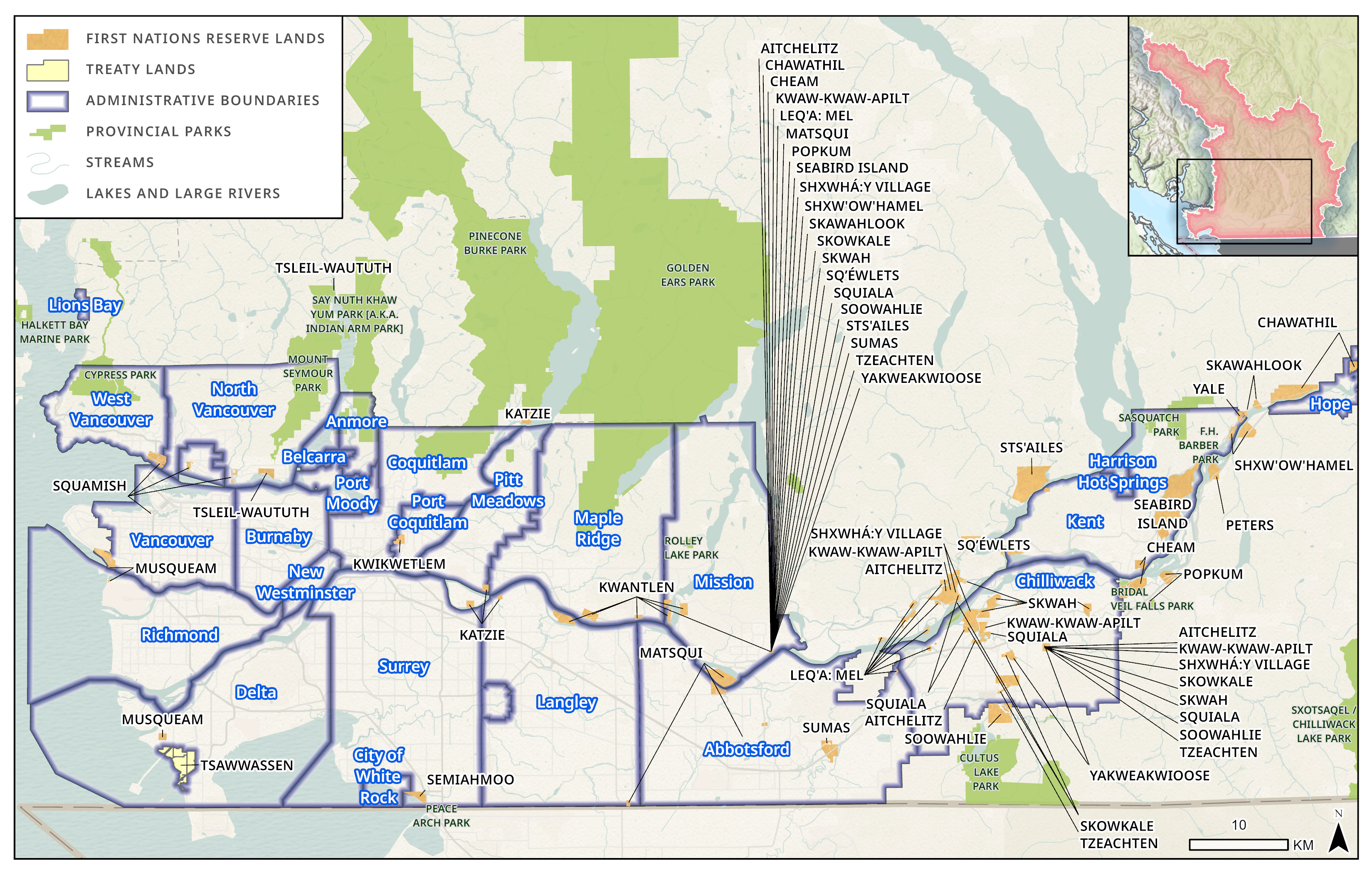

The Lower Fraser is the one of the most densely populated watersheds in BC. The upriver portion of the Lower Fraser River is bordered by the Fraser Valley Regional District and the lower portion is bordered by the Metro Vancouver Regional District. Combined, the Lower Fraser watershed is home to over 20 incorporated municipalities, more than 30 First Nation governments and communities, and roughly 3 million people. Colonization and intensive land use in the past century have brought industrial, urban, and agricultural development that has modified the environment. Much of this development occurred without consultation or cooperation with Indigenous peoples and neighbouring communities, and without a fulsome understanding of impacts to aquatic ecosystems. More than half of the historical Fraser River estuary wetlands have been diked, drained, or filled for land development without adequate consideration of impacts to salmonFootnote 15. Existing flood infrastructure has been blocking migration into several tributaries of the Lower Fraser River for many generations of salmon and other fish species. This has taken a toll on fish populations and biodiversity.

Management of the aquatic environment in the Lower Fraser is complex, with multiple authorities and overlapping jurisdictions. Federal, provincial, regional, municipal, and Indigenous governments share responsibilities for different aspects of management of the aquatic environment, and sometimes have differing or competing priorities. They must each weigh and consider the many needs and uses of the Lower Fraser, such as: Indigenous, commercial, and sport fisheries; flood infrastructure; port terminals and harbours; residential and urban development; levees and jetties for shipping lanes; reservoir dams and canals; drinking water; road and rail crossings; hydroelectric dams for power; sewage; and more. The inherent complexity of this landscape makes it very challenging to effectively manage aquatic environments for fish and fish habitat.

Aquatic habitat degradation and fragmentation

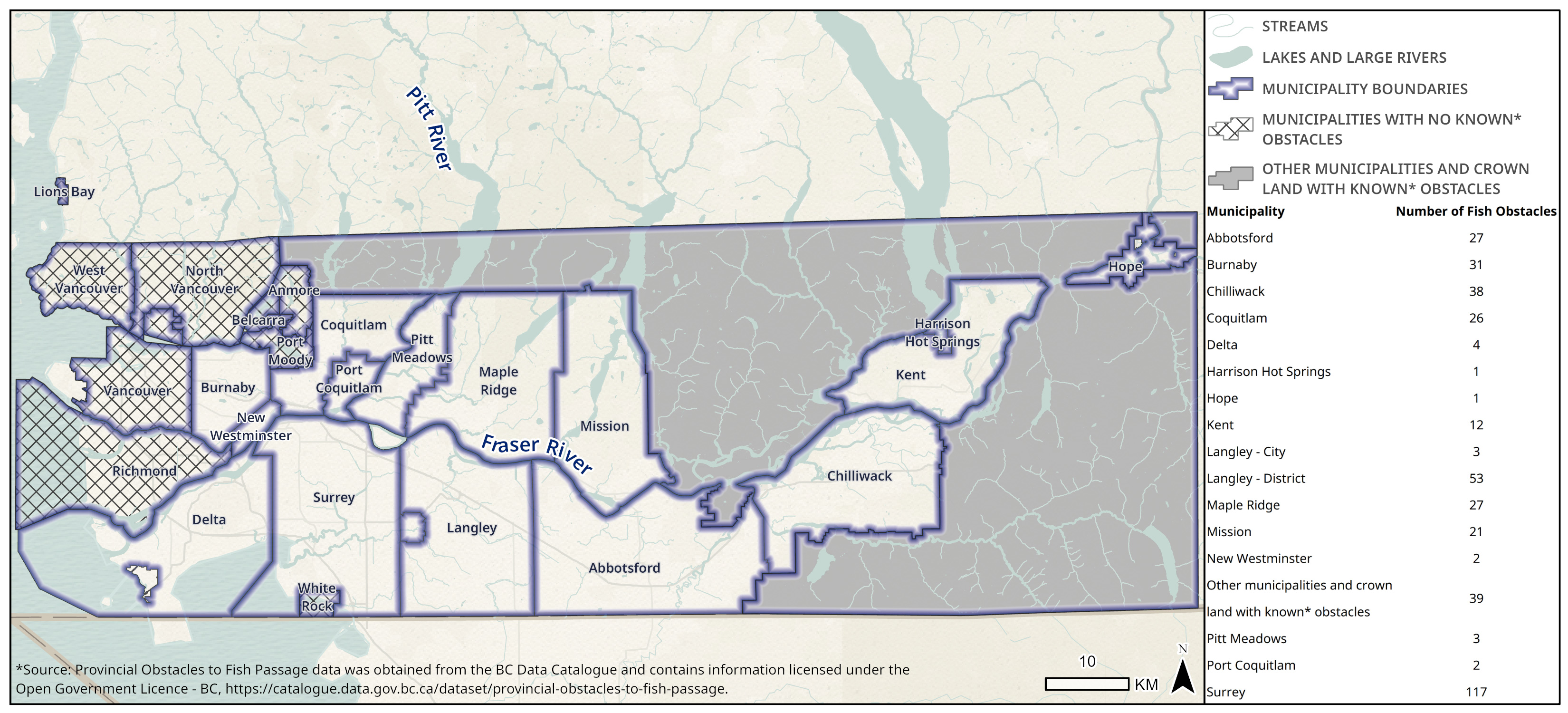

Figure 14 - Text version and data sources

| Municipality | Number of fish obstacles |

|---|---|

| Abbotsford | 27 |

| Anmore | 0 |

| Belcarra | 0 |

| Burnaby | 31 |

| Chilliwack | 38 |

| Coquitlam | 26 |

| Delta | 4 |

| Harrison Hot Springs | 1 |

| Hope | 1 |

| Kent | 12 |

| Langley - City | 3 |

| Langley - District | 53 |

| Lions Bay | 0 |

| Maple Ridge | 27 |

| Mission | 21 |

| New Westminster | 2 |

| North Vancouver - City | 0 |

| North Vancouver - District | 0 |

| Pitt Meadows | 3 |

| Port Coquitlam | 2 |

| Port Moody | 0 |

| Richmond | 0 |

| Surrey | 117 |

| Vancouver | 0 |

| West Vancouver | 0 |

| White Rock | 0 |

| Other municipalities and crown land with known* obstacles | 39 |

Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

* Provincial Obstacles to Fish Passage data was obtained from the BC Data Catalogue and contains information licensed under the Open Government Licence - BC.

Map created by DFO using data from DataBC.

The in-water footprint of some of infrastructure and activities such as diking, floodgates, pump stations, culverts, and erosion protection like riprap can be seen in the maps of the Lower Fraser River main channel. Figure 14 shows the number of verified human-caused obstacles to fish passage in each municipality of the Lower Fraser.

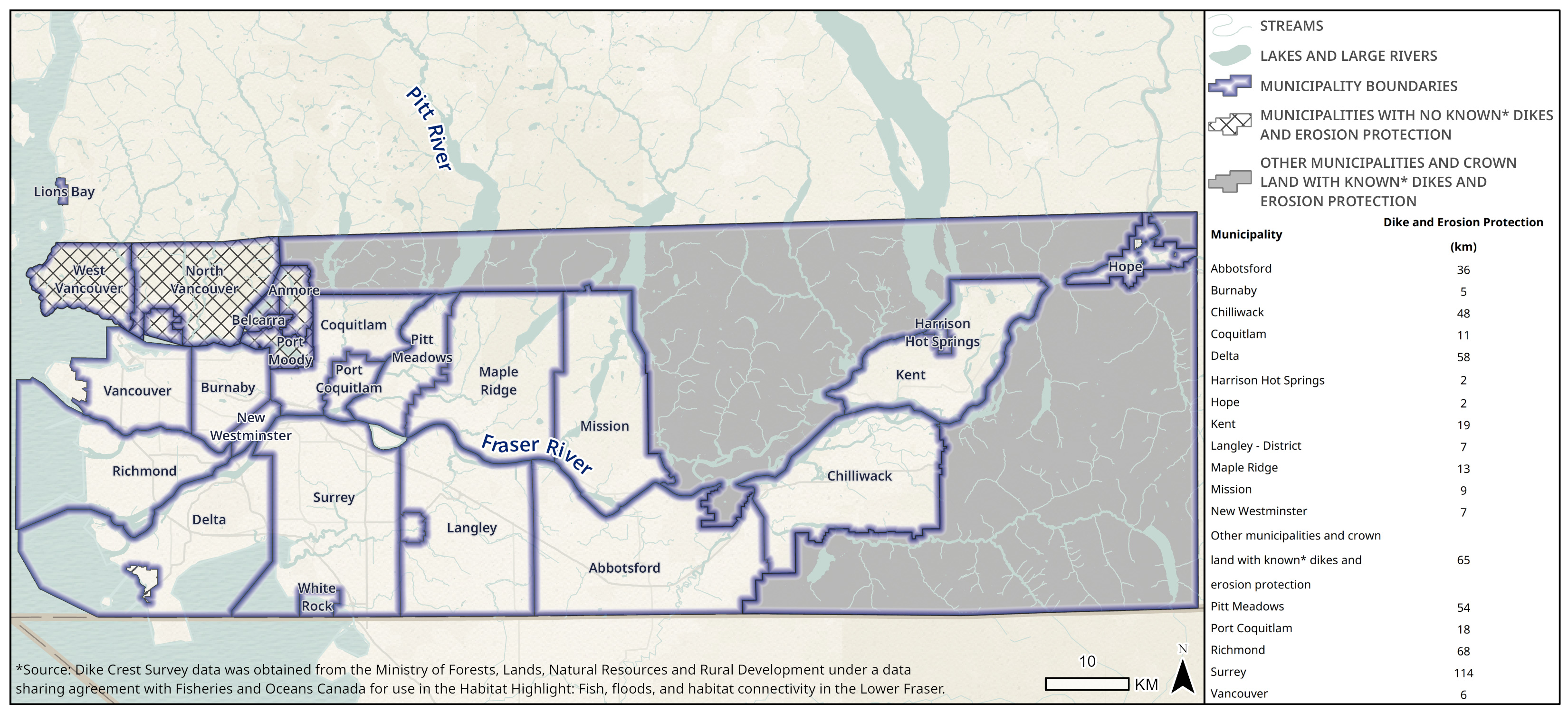

Figure 15 - Text version and data sources

| Municipality | Kilometres of dike and erosion protection |

|---|---|

| Abbotsford | 35.97 |

| Anmore | 0 |

| Belcarra | 0 |

| Burnaby | 5.00 |

| Chilliwack | 48.13 |

| Coquitlam | 11.40 |

| Delta | 58.32 |

| Harrison Hot Springs | 1.54 |

| Hope | 2.13 |

| Kent | 18.74 |

| Langley - City | 0 |

| Langley - District | 7.16 |

| Lions Bay | 0 |

| Maple Ridge | 13.02 |

| Mission | 8.82 |

| New Westminster | 7.05 |

| North Vancouver - City | 0 |

| North Vancouver - District | 0 |

| Pitt Meadows | 54.47 |

| Port Coquitlam | 17.57 |

| Port Moody | 0 |

| Richmond | 67.98 |

| Surrey | 113.62 |

| Vancouver | 5.73 |

| West Vancouver | 0 |

| White Rock | 0 |

| Other municipalities and crown land with known* dikes and erosion protection | 64.80 |

Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

* Dike Crest Survey data was obtained from the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resources and Rural Development under a data sharing agreement with Fisheries and Oceans Canada for use in the Habitat Highlight: Fish, floods and habitat connectivity in the Lower Fraser.

Figure 15 shows the total combined kilometres of verified dikes and erosion protection in rivers and streams within each municipal boundary. While these maps, created from datasets from DataBC, provide an idea of the scale of aquatic habitat modification, they only provide a modest estimate as some areas were not surveyed or lacked records and streams that have been lost from infilling, burying, or diversion are not included.

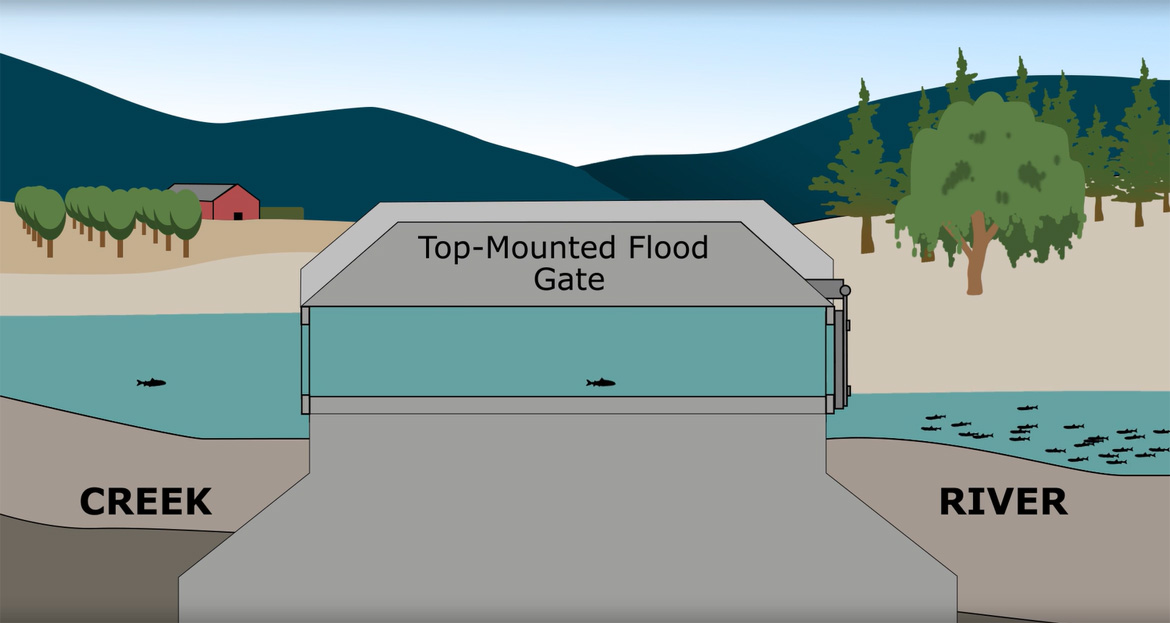

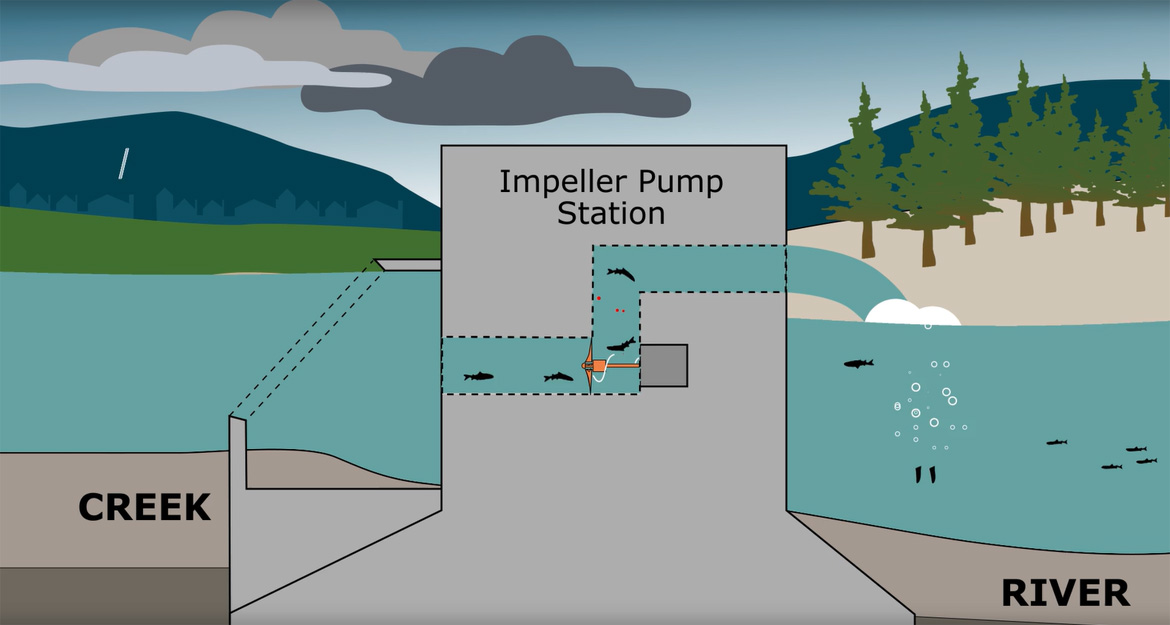

It is estimated that 135,000 to 200,000 culverts in BC impede fish passageFootnote 16. While the most common obstacle to fish passage may be culverts, it is often dikes, floodgates, and pump stations that may have the biggest population-level impacts on fish migration. This is because flood infrastructure is often situated along major rivers at intersections with large tributaries. The result is that the network of streams within an entire watershed can be blocked by a single floodgate or pump station. Blocked fish passage, along with potential water quality issues that may also be caused by this infrastructure, can be a contributing factor to declines in migratory fish populations. Figures 16 and 17, from Resilient Waters and Watershed Watch Salmon SocietyFootnote 17 illustrate this issue.

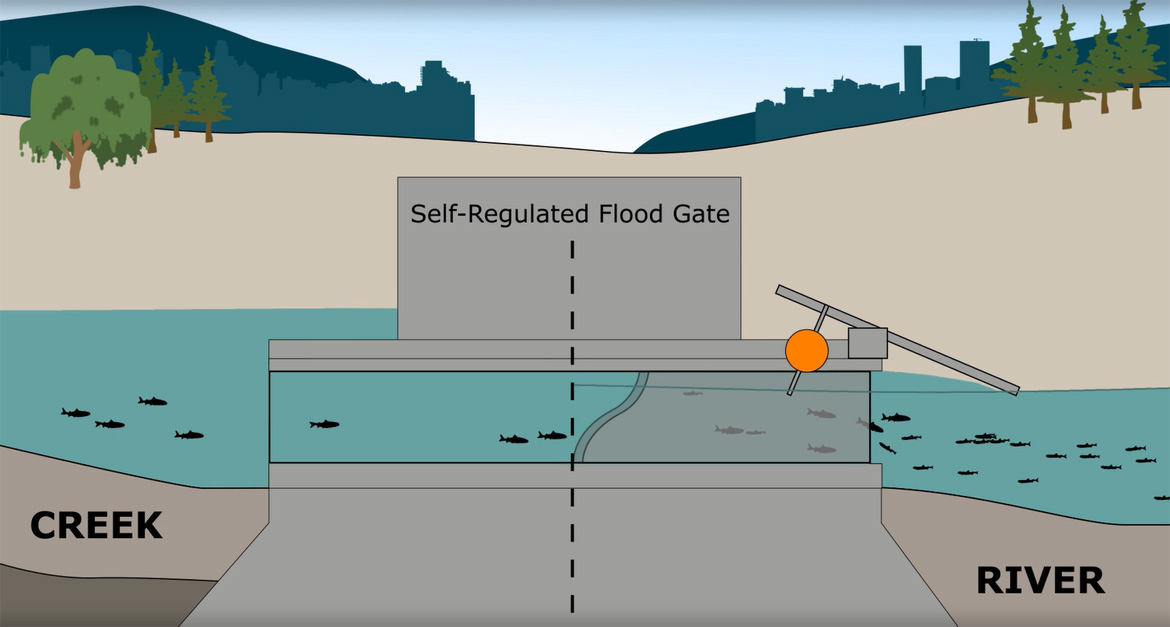

Floodgates like the popular top-mounted design have a default gate position that is closed. They rarely are opened, and then only for short periods of time. The timing of any openings is often ill-suited for fish migration and the openings can be too small for large fish. There are hundreds of floodgates across the Lower Fraser that do not have fish-friendly designs. They can block the natural migration and life cycles for fish across the regionFootnote 18.

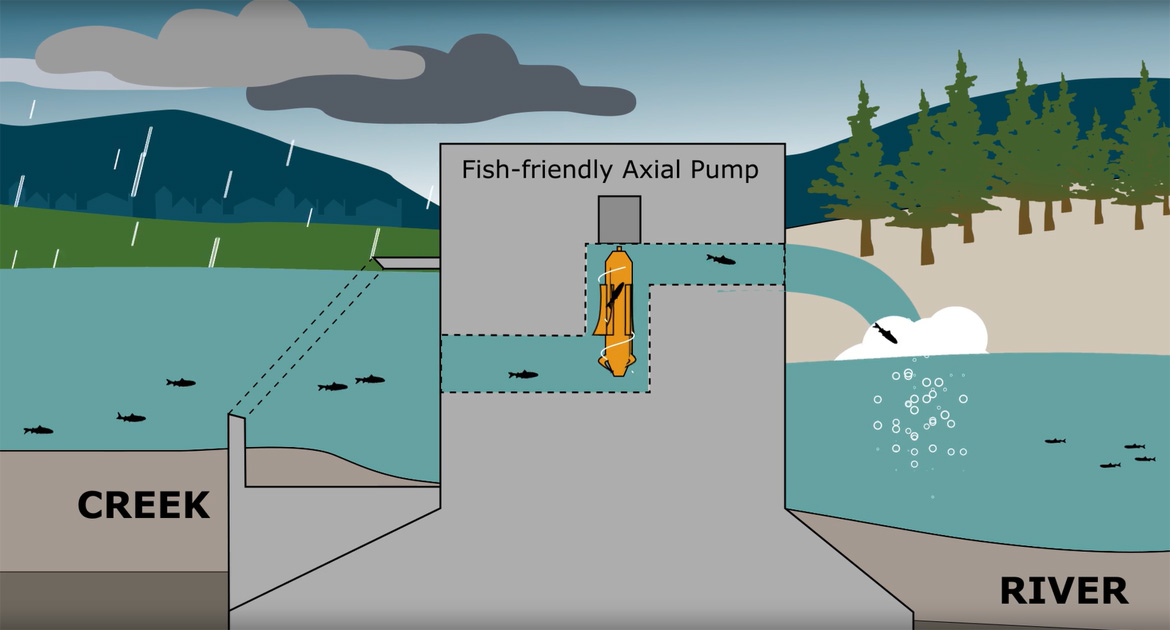

Floodgates are often paired with pump stations. Pump stations like this Impeller design (figure 17) use a fan blade that forces floodwaters through a pipe from the creek side out into the river. The fans spin quickly, often wounding or killing fish that enter the pipe. Non-fatal cuts on fish increase the chance of disease and parasite infections. The pump stations can also cause sudden changes in pressure that damage the swim bladders of fish. Like floodgates, pump stations have wide ranging impacts on the death, migration, and fitness of fish across the Lower Fraser.

Resources

Floods and the Fraser River

Within the Fraser River ecosystem, flooding is a natural and necessary ecological process that rejuvenates and connects all the aquatic habitats that make the Lower Fraser special. Most of the water in the Fraser River comes from melting snow. In the winter, snow accumulates in the mountains of the Fraser River watershed. Months of snow build-up begins to melt between May and July and pours into the streams and lakes. Combined with spring rain, the snowmelt pushes the Fraser River and its tributaries to peak water levels and flow speeds, causing the Lower Fraser River to flood. This annual May to July flooding in the Fraser River watershed is called the “freshet”.

The Lower Fraser water discharge during flood events can be so fast that fish are swept away. This can be fatal for small or young fish. Luckily, fish in the Lower Fraser are well equipped to survive and even thrive in flood events. Their physiology and behaviour are well adapted for these conditions. One way that some fish have adapted is by spawning and rearing away from the main river, such as in off-channel habitats, so that eggs and juvenile fish avoid the full brunt of floods. Another is to seek refuge within the floodplains, eddies, and off-channel habitats during floods to conserve energy and to avoid damage from debris and sediment in the main channels (Footnote 19,Footnote 20). In the case of floods, there is a clear advantage for salmon that can access spawning grounds upstream in tributaries instead of being limited to the main channel (Footnote 21,Footnote 22,Footnote 23). However, development of flood and erosion protection infrastructure is having an increasingly larger effect on how the river behaves during floods and reduces fish access to refuge habitats.

Figure 18 - Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

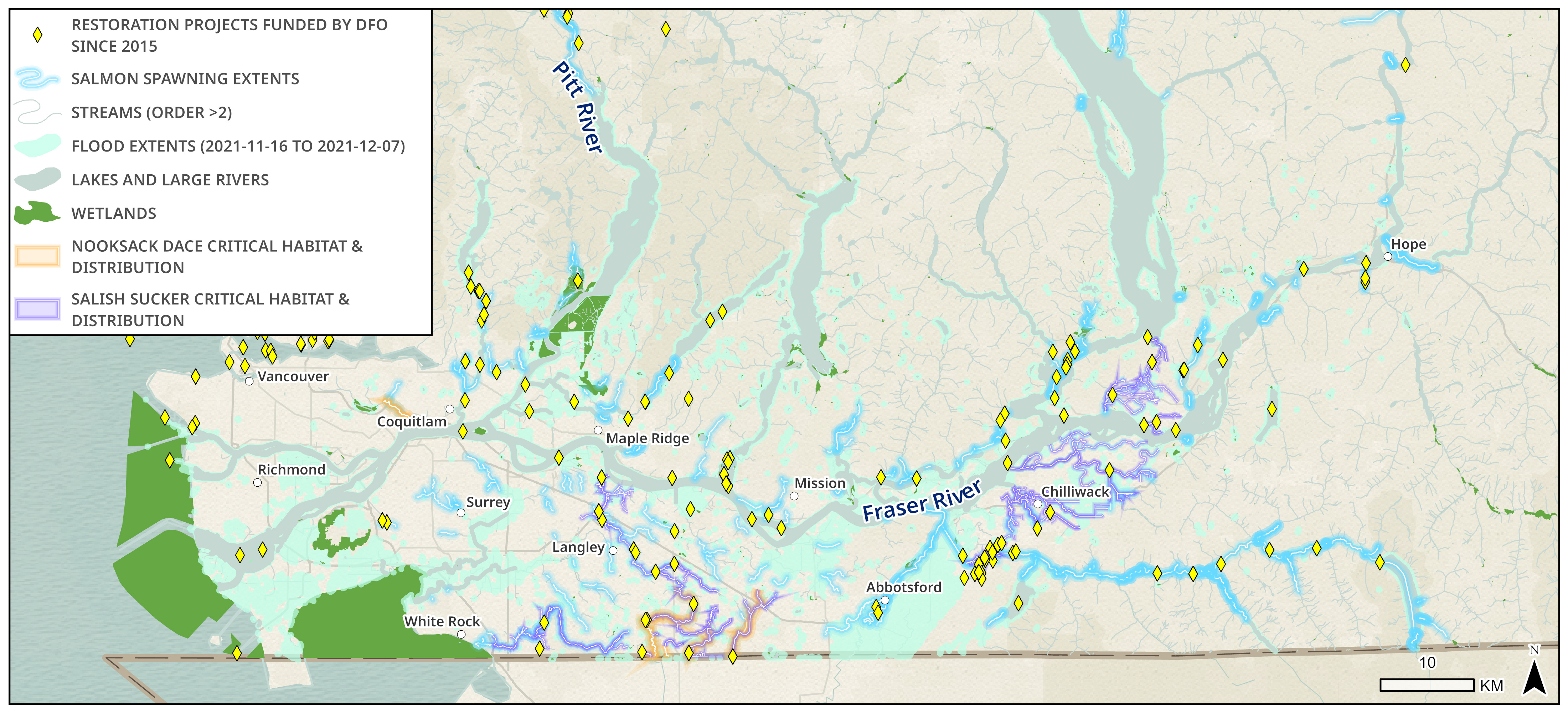

Seasonal freshet floods are expected and necessary for the Lower Fraser ecosystem. However, the severity of the 2021 floods in the Lower Fraser was unprecedented because they escalated so quickly and occurred after freshet. The flooding began on November 15, 2021, after most of southern BC region received record-breaking rainfall from an atmospheric river event. The District of Hope received 277 mm of rain in two days, by far the greatest amount of rain it has received in recorded history. This rain event was so rare, that it only had a 1% chance of occurring (i.e. a 1-in-100-year event)Footnote 24. The impact on water levels and flows in the Lower Fraser tributaries were immediate and were worsened by the additional 220 mm of rain in the Hope region from November 28 to 30Footnote 25.

DFO responded quickly to the 2021 floods by issuing emergency permits for flood infrastructure repairs and rescuing trapped fish. DFO completed aerial and ground surveys along the river in partnership with the Province of BC, Indigenous groups, and non-governmental organizations to observe impacts to fish habitat. DFO also worked to safeguard and restore access and function to its salmonid enhancement facilities and infrastructure. This included repairs to spawning channels and off-channel rearing projects.

More observations were made during the summer 2022 field season that helped better assess impacts to fish habitat, the results of which can be used to inform the prioritization of habitat restoration projects throughout the Lower Fraser that can be undertaken by partners through funding provided by DFO. Going forward, DFO is working with the Government of BC and Indigenous partners to learn from this emergency event and develop approaches and strategies to better respond to future flooding events.

The 2021 flood introduced large amounts of pollution and anthropogenic debris into the Lower Fraser. Cars, trailers, garbage, sewage, fertilizer, and other loose items were washed away from cities and roads and have contributed to plastic and chemical pollution. A map of this debris is available on the British Columbia Flood Debris Dashboard.

Resources

The human influence on flooding

Flooding is nothing new to the Lower Fraser River, but human influence has made severe flooding like the November 2021 floods more likely to occur.

The influence of climate change on flooding

Science shows us that the scale and likelihood of the 2021 fall floods were increased by climate change. The University of Victoria and Environment and Climate Change Canada, in a study entitled Human Influence on the 2021 British Columbia Floods, demonstrated that the November 2021 atmospheric river that caused the intense rains was made at least 60% more likely because of climate changeFootnote 26. The report also found that the flood and the extreme flows in the Lower Fraser watershed were made 2 to 4 times more likely because of climate change. As we begin to feel the effects of climate change in weather events today, we can also use climate science to predict impacts in the future when the effects of climate change will be more severe. For example, the chances of a catastrophic flood, or a series of moderate floods, may be 5 times more likely in 2050 than prior to climate changeFootnote 27.

The Fraser Basin Council is leading the Lower Mainland Flood Management Strategy, a collaborative initiative of 50 governmental and non-governmental agencies aimed at reducing risk and strengthening resilience to river and coastal flooding in BC's Lower Mainland regionFootnote 28. One element of this strategy has been the development of flood modelling and mapping to simulate future flood scenarios for the Lower Mainland. Notably, they have generated freshet (spring) flood scenarios under projected climate change conditions in year 2100, such as a 1-metre sea level rise and changes in peak river flows. Comparing the extent of a modelled freshet flood today to one modelled for 2100 can show the potential risks to people, fish, and fish habitat posed by a changing climate, and help us prepare for extreme events in the future.

The influence of different flood protection strategies

Land use and flood planning in the Lower Fraser has historically favoured developing in floodplains and diking rivers along their banks. As described in the Challenges and threats to aquatic habitat section, building flood protection infrastructure in this way can harm fish and fish habitat. There are many strategies for cities to protect against floods and different approaches can have different impacts on fish.

The Fraser Basin Council have used their flood modelling and mapping to predict the effectiveness of several flood mitigation strategies. These mitigation strategies include dike raising, dike setbacks, extensive dredging, land raising, and flow storageFootnote 29. Dredging to required depths for flood relief was particularly ineffective in mitigating floods from the Fraser River, as it would need to be done continuously each year which would be very costly and would harm habitat for salmon, eulachon, and sturgeon.

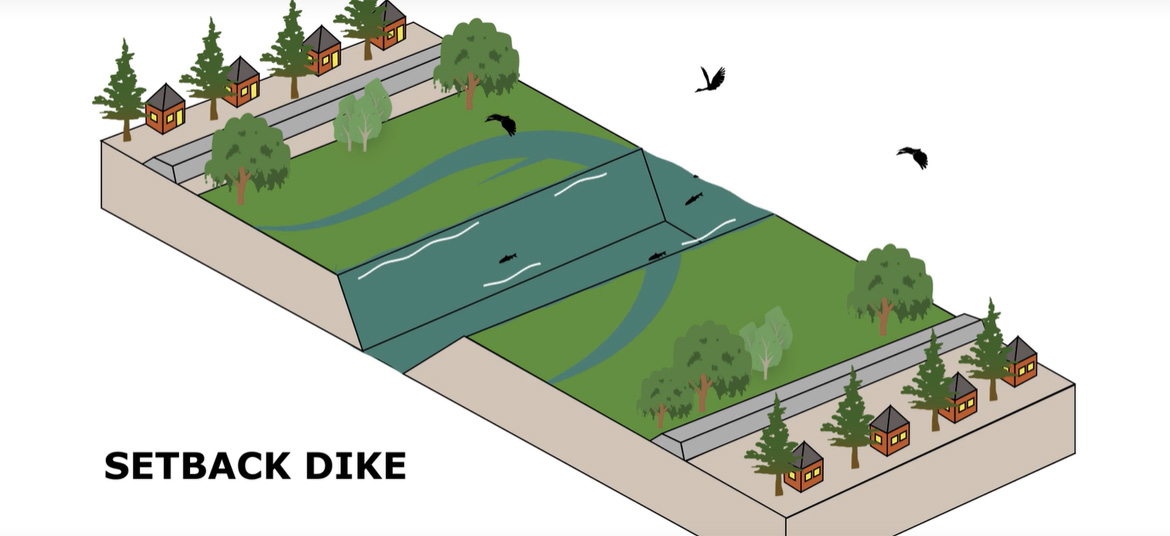

The modelling did show that there are ways to address flooding that may actually improve fish habitat, specifically approaches called nature-based solutions. The Fraser Basin Council's modelling showed that dikes with distant setbacks from riverbanks provide the river with room to naturally overflow during floods and provide shallow refuge areas for fish where flow is less extreme. On the other hand, raising dikes right at the Fraser River banks blocks off floodplains that absorb and temper floods, effectively “squeezing” the river tighter and increasing the amount of flooding for land downriver. Unfortunately, building dikes right up to riverbanks is common practice. In their dike setback scenario for the Fraser River near Chilliwack, the Fraser Basin Council found river flood level heights were 0.15 metres lower than diking at the riverbanks. Not only was flooding less likely to go over dikes, but this dike setback scenario had the added benefit of creating approximately 6 square kilometres of seasonal floodplain fish habitat. This nature-based solution can be beneficial for people and the environment. These types of solutions need to be considered first for infrastructure owners in the Lower Fraser to help fish populations succeed and reduce the long-term costs to people and the environment.

Resilient Waters and the Watershed Watch Salmon Society have created animations to demonstrate the many benefits of dike setbacks. Land, property, and people are still protected by dikes while the setbacks provide more floodplain for fish to seek temporary refuge.

Working with others to protect fish and fish habitat in the Lower Fraser

DFO staff in Pacific Region work with others to protect and restore fish habitat in the Lower Fraser and in other watersheds across British Columbia and the Yukon in a variety of ways.

We are modernizing to better protect fish and fish habitat

Since 2019, the Fish and Fish Habitat Protection Program has continued to modernize by building an array of policy, monitoring, planning, and regulatory tools to achieve its goals. Our mandate has expanded to collaborate with provinces, territories, regional and municipal governments in land use planning to help better protect and restore fish habitat. For example, through the Nicola Watershed Restoration Committee in the BC Interior, we have been working closely with the Province of BC, the Scw'exmx Tribal Council, Nooaitch Indian Band, Lower Nicola Indian Band, the City of Merritt, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, the Pacific Salmon Foundation, the Thompson Nicola Conservation Collaborative, the University of BC, fisheries consultants, and many others to examine a broad range of challenges and opportunities to further restoration in the Nicola watershed, which is chronically impacted by wildfires, drought, and flooding.

We've also been developing the cartographic and data visualization products featured in this Habitat Highlight. With the help of dashboards and watershed-specific metrics, we can make data-driven decisions to prioritize where and how to protect and restore fish habitat in this sensitive and important region. We are also developing web applications to centralize data that has been sourced from various organizations so that large amounts of data can be accessed more effectively.

We are undertaking pilot planning processes in the BC Interior and the Yukon as part of funding received under the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative. As part of the Integrated Planning for Salmon Ecosystems initiative our efforts to date have been focused on the Thompson-Nicola region to develop collaborative planning tables aimed at bringing together key partners and jurisdictions to develop Integrated Salmon Ecosystem Plans that identify threats and pressures facing salmon habitats, define priority actions, and develop approaches and recommendations for enabling better outcomes for salmon and their habitats. Work to establish a similar process in the Yukon is anticipated to progress early in 2023.

We foster and fund partnerships to restore habitat

One of the many ways DFO is improving habitat quality and connectivity in the Lower Fraser is by partnering with communities and non-profits to fund impactful restoration projects. DFO provides habitat restoration funding through programs such as the BC Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund (BCSRIF), the Aquatic Ecosystems Restoration Fund (AERF), the Canada Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (CNFASAR), and the Indigenous Habitat Participation Program (IHPP). All of these programs combined have provided hundreds of millions of dollars for habitat restoration projects led by non-profits and Indigenous communities, many within the Lower Fraser.

In a study completed by the Raincoast Conservation Foundation (Raincoast), over 60% of the funding for aquatic habitat projects from 2009 to 2019 came from federal government bodies like DFO. These funds supported activities like:

- restoration of riverbanks and floodplains, to reduce erosion, buffer against extreme flooding, and serve as seasonal habitat for wetland species

- reconnection of wetlands and estuaries (i.e. removing barriers to fish passage between these habitats) to restore water movement, improve filtration, and provide access to shelter and food for young fish

Figure 22 - Text version and data sources

| Project location | Project description | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Addington Point Marsh | Expand existing dike breaches or fully remove dikes to improve tidal exchange | Field work |

| Backwash (Ferry Island) Slough | Build box culvert to reconnect through existing causeway (Rosedale Ferry Rd) | Field work and planning |

| Bon Accord Creek | Modify existing floodbox | Investigation required |

| Chester Creek | Investigate pump and gate for fish passage | Unknown |

| Chillukthan Slough | Upgrade to fish-friendly pump and gates | Early planning |

| DeBoville Slough | N/A - reference site | Field work |

| Deas Slough | Breach existing causeway (Deas Island Rd) | Field work |

| Hatzic Pump Station | Change operational regime of floodbox and/or pump station to improve fish passage | Field work |

| Lower Agassiz Slough | Replace existing floodbox | Field work |

| Lower Nelson Slough | Install fish-friendly floodbox in dike | Field work |

| Lower Tilbury Slough (Gravesend Reach) | Modify or replace existing floodbox | Field work and planning |

| Maple Creek | Replace existing submersible pumps with permanent fish-friendly pump station and upgrade floodbox flapgate and trash rack | Planning |

| McLean Creek | Modify and/or replace existing floodbox and pump station | On hold |

| McLennan Creek | Modify or replace existing pump station and floodbox | Field work |

| Pitt-Addington Marsh | Construct new dike along southern WMA boundary and breach or remove existing dike | Limited field work and awaiting strategic planning |

| Salmon River | Investigate fish passage at pump and gate | Unknown |

| Sea Island Conservation Area | Replace existing dike with new dike set back from river | Limited field work |

| Skumalasph Slough | Install fish-friendly floodbox | Limited field work |

| Sq'ewlets East Slough | Open redundant secondary dike at river bank to reconnect existing slough | Data collection via other project |

| Sq'ewlets West Slough | Modify or replace existing floodbox | Data collection via other project |

| Squawkum Creek | N/A - reference site | Field work |

| Taylor Road Slough | Modify or replace existing floodbox | Field work and planning |

| Upper Cheam Slough | Breach existing causeway (Bridge Rd) and construct channel to connect slough to river | Field work |

| Upper Hope Slough | Breach primary dike and install fish-friendly floodbox to connect to Backwash Slough | Field work |

| Upper Tilbury Slough | Modify or replace existing floodbox | Field work |

| West Creek | N/A - reference site | Field work |

| Yorkson Creek | Change operations at fish friendly pump station | Field work and planning |

| Zaitscullachan Slough | Install fish-friendly floodbox and channel through dike | Field work and planning |

Data sources for base map

Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), City of Maple Ridge, DeLorme, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Environmental Systems Research Institute Canada (ESRI Canada), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Garmin, Here, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (METI/NASA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NaturalVue, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Coast Guard Survey (NOAA OCS), National Parks Service (NPS), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Parks Canada, SafeGraph, United States Geological Survey (USGS).

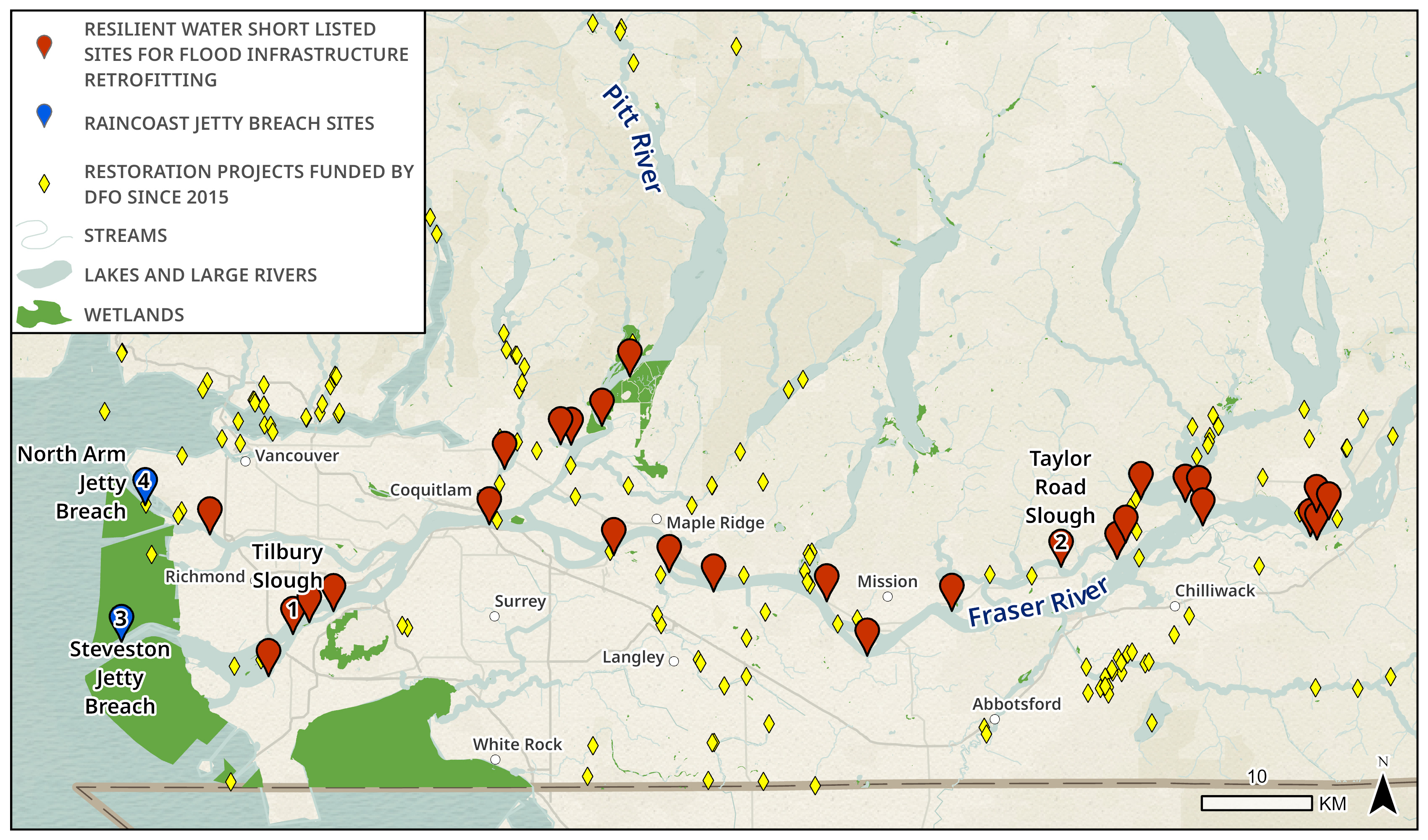

For example, the BCSRIF program funded Resilient Waters to enable their work in identifying over 150 pieces of non-fish-friendly flood infrastructure that are fragmenting fish habitat and blocking fish migration in the Lower Fraser. Resilient Waters completed this work with its partners at Kerr Wood Leidal, Pearson Ecological, Watershed Watch Salmon Society, and local Indigenous governments like the Kwikwetlem (kʷikʷəƛ̓əm) First Nation. Resilient Waters has narrowed down its list of non-fish-friendly infrastructure to 26 high-priority sites in need of fish-friendly upgrades near the main reaches of the Lower Fraser River. This short list of projects can be seen in figure 22.

Below, in figures 23 and 24, are some examples of the types of fish-friendly infrastructure that could be installed at these high-priority sites, such as self-regulated floodgates and axial pumps. The completion of these projects would restore continuous fish access to hundreds of kilometres of important off-channel spawning and rearing fish habitat without reducing flood safety in these areas. DFO is proud to continue supporting Resilient Waters' work as they move to the implementation phase of some of their projects. For example, BCSRIF is directly funding two projects on their list: flood infrastructure retrofits at Lower Tilbury Slough and Taylor Road Slough which can be seen as #1 and #2 in figure 22.

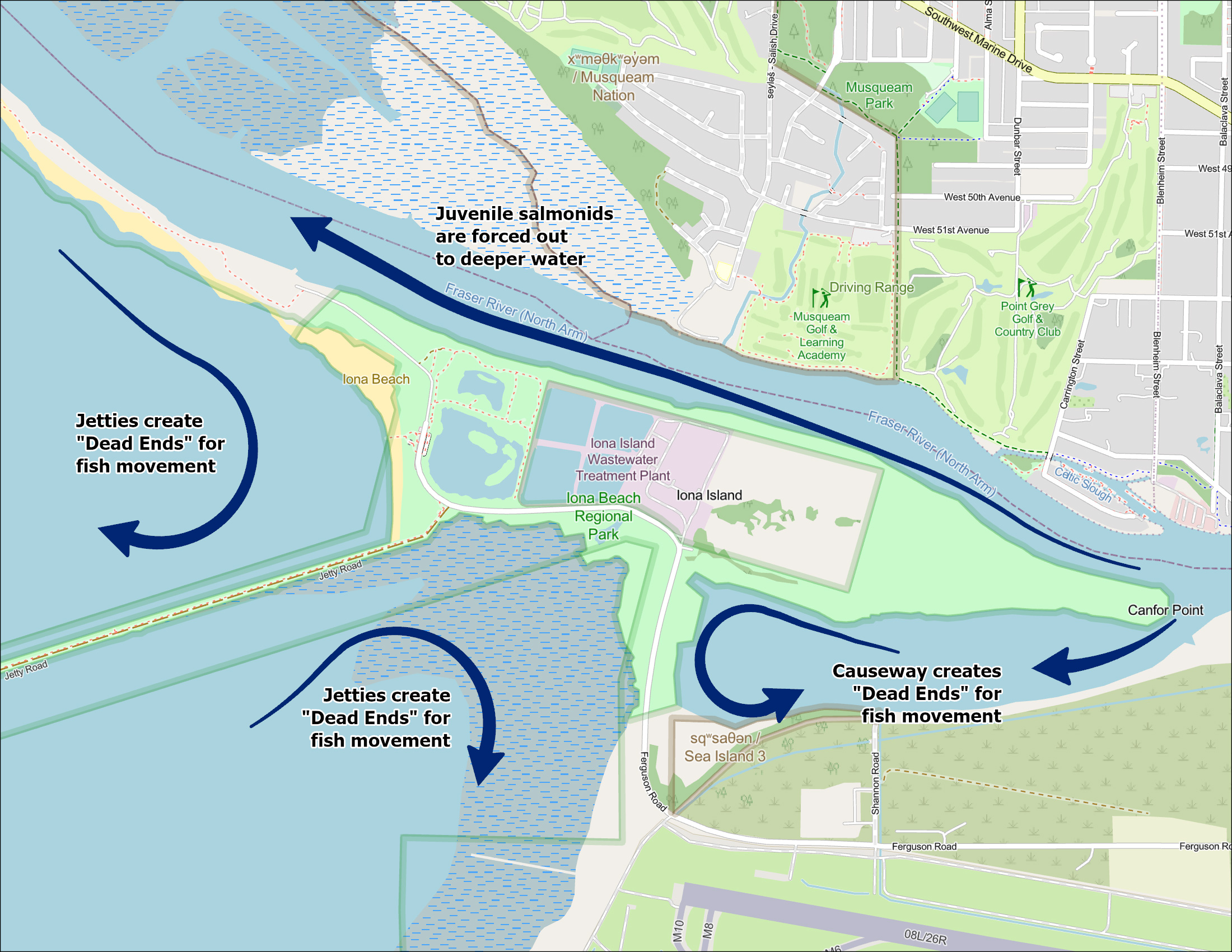

DFO's Coastal Restoration Fund (CRF) supported some of the Raincoast Conservation Foundation's work to restore the Lower Fraser's connection to its saltwater marshes and estuarine habitats. The Steveston and North Arm jetties west of Richmond were installed decades ago to establish shipping lanes, but the infrastructure has resulted in habitat fragmentation between the Fraser River and its outer estuary. As a result, out-migrating juvenile salmon in the Fraser River must work significantly harder to reach estuarine habitats critical for their fitness and survival. Raincoast and its partners have risen to the challenge to plan and lead jetty breaching projects to improve access to important estuarine habitats for salmon and other fish. DFO's CRF program provided long-term (>5 years) funding and staff expertise to support this work. Now that Raincoast has breached the Steveston and North Arm jetties (#3 and #4 on figure 25), their research indicates that thousands of juveniles from all species of salmon are utilizing the breaches and benefiting from increased access to important feeding and rearing habitats. Combined, the jetty breaches represent the largest connectivity restoration project undertaken in the Fraser River estuary over the last few decades.

Source: Metro Vancouver and Raincoast.

Resources

- DFO funding opportunities for Indigenous-led fish conservation projects

- Resilient Waters priority projects for fish-friendly upgrades

- Raincoast jetty breach projects to reconnect the Fraser River Estuary and support salmon

How you can help

Here are a few ways you can help protect fish and fish habitat in the Lower Fraser River watershed:

- learn about your local streams:

- are there streams in your neighbourhood that are lost or degraded?

- how are they connected to the major rivers in your watershed?

- are there streams in your neighbourhood that are now channelized and flow subsurface in culverts, and can they be day-lighted?

- get your municipality involved:

- ask your municipality to lead, sponsor, or support the replacement of old flood and erosion protection infrastructure with fish-friendly versions that enable fish migration and healthy riparian habitats. Take a look at some of the projects on the Resilient Waters website for inspiration

- reduce pollution run-off:

- impermeable surfaces do not absorb rainwater and can contribute to flooding. Contaminants like oils, plastic, metals, and chemicals are washed away into river systems instead of remaining at their source. To reduce run-off and the pollution it brings into the river, look for ways to increase the permeability of land in your community. Some ways to do this include disconnecting downspouts from sewer systems, installing rain barrels, and planting rain gardens. Permeable pavers, gravel beds, and green roofs also help reduce run-off. Ask for your municipal government to provide support and incentives to take action

- volunteer:

- serve as a stream monitor for a local watershed organization to collect data and contribute to smart water management. For example, look for opportunities to join a local Streamkeepers group and work together with them to care for streams in your community

- launch a restoration project in your community

- find tools and information for starting a habitat restoration project in your area here: DFO's salmon enhancement guide to community involvement

Additional resources

- BC MOE. 2022. Sturgeon Bank Wildlife Management Area. Accessed 2022.

- Boyd, Lindsey, Paul Grant, Lemieux Jeffrey, and Josephine C. Iacarella. 2022. "Cumulative Effects of Threats on At-Risk Species Habitat in the Fraser Valley, British Columbia." Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.

- Boyle, C.A., L. Lavkulich, H. Schreier, and E. Kiss. 1997. "Changes in Land Cover and Subsequent Effects on Lower Fraser Basin Ecosystems from 1827 to 1990." Environmental Management.

- Bush, E., B. Bonsal, C. Derksen, G. Flato, J. Fyfe, N. Gillett, B.J.W. Greenan, et al. 2022. Canada's Changing Climate Report in Light of the Latest Global Science (PDF, 1,110 KB). Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- DFO. 2022. "Fraser River Environmental Watch Report." Fisheries and Oceans Canada. September. Accessed 2022. https://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/habitat/frw-rfo/reports-rapports/2022/docs/2022-09-15-eng.pdf

- Ellis, Erica, and Michael Church. 2005. "Hydraulic geometry of secondary channels of lower Fraser River, British Columbia, from acoustic Doppler profiling." Water Resources Research (Water).

- Giannico, Guillermo R., and Michael C. Healey. 1998. "Integrated Management Plan for a Suburban Watershed: Protecting Fisheries Resources in the Salmon River, Langley, British Columbia." Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2203.

- Gregory, Robert, and Colin Levings. 1998. "Turbidity Reduces Predation on Migrating Juvenile Pacific Salmon." Transactions of the American Fisheries Society (Am) 275-285.

- Mantua, N. J., I. Tohver, and A. F. Hamlet. 2009. Impacts of Climate Change on Key Aspects of Freshwater Salmon Habitat in Washington State. Seattle, Washington: Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington.

- Pacific Salmon Foundation. 2021. Pacific Salmon Explorer: Fraser Pressure Risk Indicators. Accessed 2022.

- Date modified: